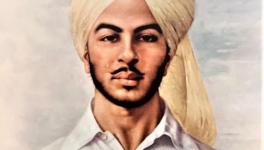

Sukhdev: Portrait of a Revolutionary

On 23rd March 1931, three Indian Marxist revolutionaries, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Shivram Hari Rajguru, were hanged by the British for waging a war against the colonial state.

Sukhdev was a central committee member of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), formed on 8 September 1928 by anti-colonial revolutionaries of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajputana (now Rajasthan), and its organisation in-charge in Punjab. He was the chief accused in the Lahore Conspiracy case of 1929-30, which put to trial at least a dozen HSRA revolutionaries for the murder of JP Saunders, the assistant superintendent of Lahore Police.

He was known by various aliases in the party—“villager”, “dayal”, “swami” and others. Born on 15 May 1907 in Ludhiana, Sukhdev was raised by his paternal uncle Lala Achintanram who was a well known Arya Samajist and Congress activist. He joined the National College in 1921 and came in contact with revolutionary-minded youths including Bhagat Singh, Bhagwati Charan Vohra and Yashpal. He joined the underground revolutionary organisation Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) which declared itself socialist in 1928.

Initially, Sukhdev and his friends were greatly influenced by the anarchist ideas of the father of anarchism, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin, but it is interactions with early Indian communists such as Chhabil Das and Sohan Singh Josh that brought them closer to Marxism. They decided to form an open mass-organisation, called the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, to mobilise students and youth of Punjab to work amongst the workers and peasants. They also formed the Lahore Students Union and Bal Bharat Sabha for college and school students respectively.

In 1928, anti-Simon Commission protest demonstrations led to the death of Punjab’s famous leader, Lala Lajpat Rai, due to the injuries he suffered during a police lathi-charge. Although Sukhdev and Bhagat Singh were very critical of Rai due to his communal politics (they were even banned from entering his bungalow), HSRA decided to avenge his death as they viewed it as a national insult inflicted by the colonial bureaucracy. Sukhdev, who was already in charge of Punjab, was the mastermind of this action which was successfully executed by Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad, Rajguru and others.

In 1929, the HSRA revolutionaries threw two harmless bombs inside the National Legislative Assembly, in protest against the Public Safety Bill and Trade Dispute Bill and courted arrest. Sukhdev and his comrades were arrested in May that year in Lahore and, along with others, faced trial in the Lahore Conspiracy Case.

In jail, HSRA revolutionaries undertook the famous hunger strike for the rights of political prisoners, which made them immensely popular throughout India and beyond. Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were given capital punishment.

Sukhdev: A revolutionary intellectual

Both in academic historiography and the popular public imagination, Sukhdev remains a less-discussed figure. The reasons for his relative marginalisation include the fact that other martyrs such as Bhagat Singh and Azad loom large over the imagination of revolutionary movements of India. This is chiefly because of the heroic acts they accomplished. Sukhdev was not directly involved in any action which has remained in public memory.

Also, compared with comrade and friend Bhagat Singh and other revolutionaries such as Ram Prasad Bismil, Sukhdev has left behind very few writings. There are only five documents written by him which are available in the public domain.

A third reason is that academic research on Indian revolutionary movement of the colonial period is mainly centred on the figure of Bhagat Singh (and revolutionaries of Bengal), given their massive popularity. Historian Kama Maclean has ascribed this to the widespread circulation of Bhagat Singh’s famous photo, in which he wears a hat. It was taken just before Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt threw bombs in the Assembly. In her 2016 book, A Revolutionary History of Interwar India: Violence, Image, Voice and Text, she notes that even before their hanging, “the condemned trio were frequently referred to in the press as ‘Bhagat Singh and others’ or ‘Bhagat Singh and his comrades’. This, she points out, occurred to the extent that Bhagat Singh’s full name was frequently used as shorthand for the revolutionary movement at large.

So in the popular public imagination of revolutionaries—which is also largely a romantic one—propagated in history textbooks and representations in cinema, Sukhdev remains an “accomplice” of Bhagat Singh. The truth is that all HSRA revolutionaries were ideologues and serious activists in their own right. Shiv Verma, a comrade of Sukhdev, writes in his memoir that “after Bhagat Singh, it was Sukhdev who was well equipped with socialist literature”.

The revolutionaries were accused by the British government and a section of Indian leaders, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, of mindless violence and terrorism. The revolutionaries Bhagwati Charan Vohra and Bhagat Singh, and Sukhdev, had debated the issue of violence with Gandhi. In two letters from Sukhdev to his comrades, we clearly find his strong denouncement of terrorist actions and his view that they were divorced from the ideology of HSRA. Sukhdev emphasises that the primary task of revolutionaries should be to arouse public support, who then had to be initiated into a revolutionary programme. Violence was not an end in itself, rather a method of political propaganda and struggle.

In a reply to Gandhi’s call for “peace” and ceasing the armed revolutionary struggle in the wake of the Gandhi-Irwin pact, Sukhdev very clearly said that the HSRA and the revolutionaries “stand for the establishment of the socialist republic”, and will “carry on the struggle till their goal is achieved...”. As a political ideologue and strategist, Sukhdev argues with Gandhi that “…peace and compromise is but a temporary truce which only means a little rest to organise better forces on a larger scale for the next struggle”.

The impact of Marxist-Leninist thought can be clearly seen in his exposition of tactics to carry out the revolutionary struggle. In the same letter, Sukhdev writes, “Revolutionary struggle assumes different shapes at different times. It becomes sometimes open, sometimes hidden sometimes purely agitational and sometimes a fierce life-and-death struggle. In the circumstances, there must be special factors, the consideration of which may prepare the revolutionaries to call of their movement.”

He also criticises Gandhi for not providing any concrete reason for cessation of revolutionary movement and argues that “mere sentimental appeals do not and cannot count much in the revolutionary struggle”. Interestingly, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru, in their last petition to the Governor of Punjab, use these exact words to describe the state of war between the Indian masses and the imperialism-capitalism combine. These lines are clearly inspired by the opening lines of the Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which they originally published in February 1848.

As a political thinker and strategist, Sukhdev’s chief concern was building a robust revolutionary organisation. Shiv Verma notes in his memoir: “In reality, Bhagat was the political mentor of the Punjab party; Sukhdev was the organiser—one who built its edifice brick by brick...”

Till the very end of his life, Sukhdev was primarily concerned with building this revolutionary organisation. In two letters from jail to his comrades, he highlights why such an organisation was needed. The first reason, he said, was that the revolutionaries had been able to capture the imagination of people through their actions and now they had to be educated in the revolutionary programme. Second, because “high-class leaders had betrayed the revolutionaries”, therefore, there was urgent need for a mass political party whose objective would be to educate the masses about the meaning of revolution. Its task would be to develop a separate line of struggle, against Gandhi. He suggested the name Red Revolutionary Party for it: it would carry out revolutionary work, forming committees, and undertake propaganda through all means, legal or not.

To Sukhdev, the first step towards becoming a revolutionary was to have a “revolutionary education”. In another letter to his comrades, he writes “...success of revolutionary movement depends on how much our workers understand revolutionary ideals, tactics and struggle”. In the letter are clear influences of VI Lenin’s concept of “professional revolutionary”. He writes, “Only those people are capable of carrying out a revolutionary struggle who have ‘self-sacrificing devotion’, who are well equipped with ‘revolutionary education’ and those who understand revolutionary project as their ‘profession’”.

An in-depth study of world revolutions and revolutionary thought and a scientific analysis of Indian society and politics made Sukhdev and his comrades confident about the need of a society based on socialist principles to take India out of abject poverty, hunger, illiteracy, unemployment, feudal and imperialist oppression and exploitation. The intellectual development of Sukhdev was a classic example of ‘praxis’; his knowledge and understanding about movement and party grew out of his engagement with broader socialist literature and with his engagement as a revolutionary activist with Indian society.

Harshvardhan and Prabal Saran Agrawal are doctoral candidates at CHS and CSS, JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.