Why the A-G Refused to Prosecute Jagan Reddy for Contempt

The Attorney-General has, once again, declined consent to prosecute Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy. The question is, why is the BJP lawyer in question repeatedly seeking the consent of the AG?

On 6 October, Jagan Reddy had alleged a nexus and lack of objectivity in the judiciary of Andhra Pradesh, and charged sitting Supreme Court judge NV Ramana with exercising undue influence, while requesting the Chief Justice of India to examine the matter and consider steps “as may be considered fit and proper” to ensure the state judiciary’s neutrality. The CM alleged that the senior apex court judge had proximity to Telugu Desam Party (TDP) chief Chandrababu Naidu, and that a “former judge of the honourable Supreme Court [had] placed this fact on record”. On 10 October, his letter and associated documents were released to the media.

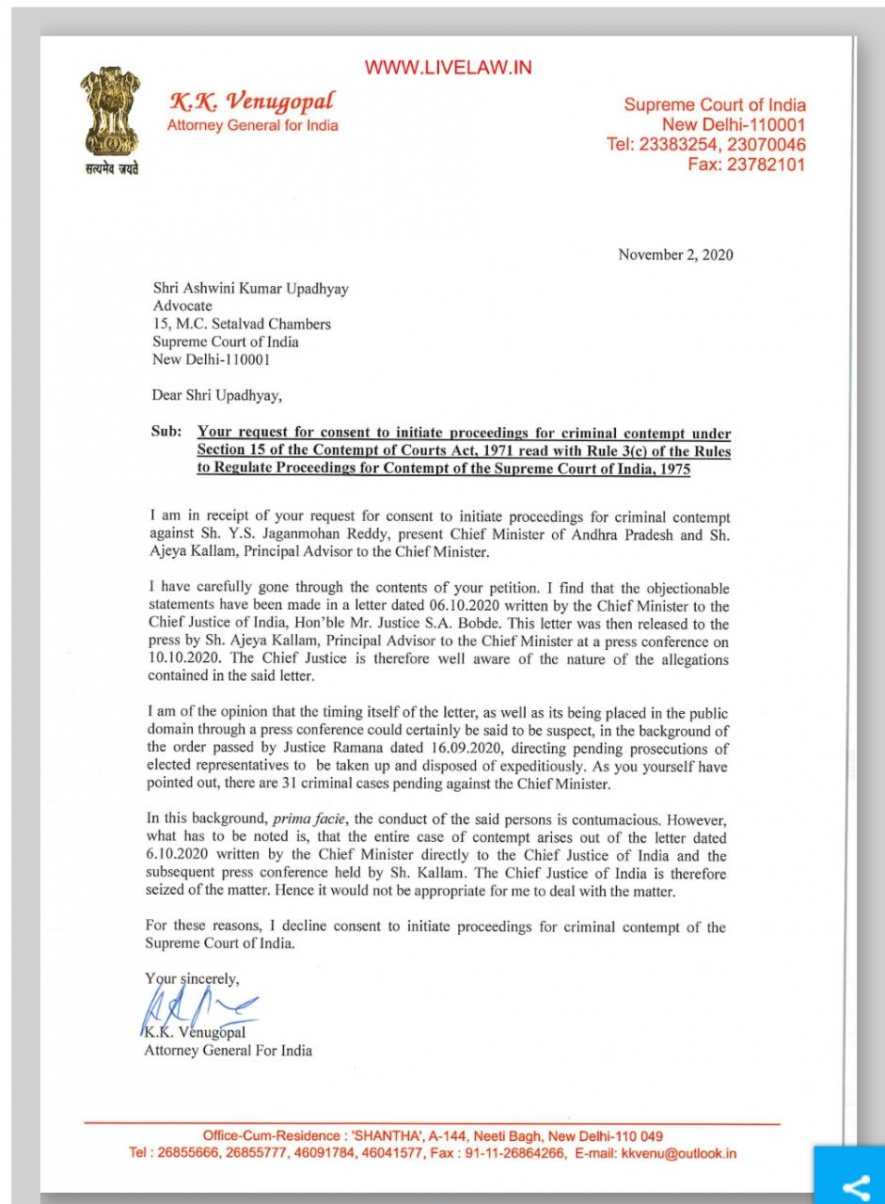

Thereafter, Supreme Court advocate Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay, who is associated with the Bharatiya Janata Party, wrote to the Attorney General of India (AGI) and sought his consent to prosecute Reddy for contempt of court. On 2 November, describing the time chosen by the Andhra CM to publicise his complaint as “suspect”, the AG, KK Venugopal, did not agree to initiate contempt proceedings. This left the field open to the CJI, before whom the controversial complaint has been placed.

It is important to note that Venugopal did not endorse the letter of the Chief Minister, nor the publicity it got. He found the statements in the letter objectionable, its timing suspect and prima facie, the conduct of the CM and his principal advisor “contumacious”. However, he felt it appropriate not to interfere on grounds that the CJI was already seized of the matter. The entire basis of the petition filed by Upadhyay is the “complaint” of the Chief Minister, which is already placed before the CJI, and therefore he decided not to initiate yet another proceeding in the matter.

To be clear, there are three methods of initiating a contempt of court proceeding.

1. The SC and High Courts can take up a case on its own motion;

2. On the motion of the AGI and,

3. On the motion of any person with the consent of the AGI.

It is worth nothing that none of these methods was taken up in the recent Prashant Bhushan case. An advocate, Mehek Maheswari, filed a petition seeking “suo motu” initiation of contempt proceedings under Article 129 of the Constitution, which relates to inherent powers of the Supreme Court. The court had accepted this petition. According to the Free Press Journal, Maheshwari (as per his own LinkedIn profile), is a self-proclaimed life coach who has previously assisted in cases such as the National Herald case, Ram Mandir case, Sunanda Pushkar murder trial, Tirupati temple matter and so on. He was also an associate in Subramanian Swamy’s office.

To sum up, the SC did not initiate contempt proceedings against Bhushan on its own motion. Nor did Maheswari ask the AGI to consent to the proceedings. Instead, he filed a petition reminding the SC of its inherent powers. With this, the SC discovered a fourth route—not recognized by the law—to condemn critics for speaking out against judges. Neither the Constitution nor the Contempt of Court Act (CCA), 1971, provide for this route. As per the Constitution, the SC cannot entertain any petition directly unless a fundamental right has been breached—but Maheshwari’s fundamental rights were not affected by Prashant Bhushan.

If the AG thinks it appropriate, he can initiate a motion of contempt of court before the constitutional courts.

The third method is to file a complaint under the CCA 1971, by any person. According to this Act, unless consent is obtained from the AG, nobody can initiate contempt of court proceedings in the SC. If any person wants to proceed before a High Court under this Act, he must seek consent of the AG. Generally, this power is used to ensure compliance of the orders of the court if a concerned officer does not implement it. This step, involving the top advocate of the state, will ensure enforcement of the order. But now, it is being used to condemn “criticism of court”, in the name of calling it “scandalisation”.

These methods of initiation are explained in section 15 of the CCA, 1971, which says: Cognizance of criminal contempt in other cases (1) In the case of a criminal contempt, other than a contempt referred to in section 14, the SC or the HC may take action on its own motion or on a motion made by (a) the Advocate-General, or (b) any other person, with the consent in writing of the AG, in relation to the HC for the Union territory of Delhi, such Law Officer as the central government may, by notification in the official gazette, specify in this behalf, or any other person, with the consent in writing of such Law Officer.

As per the explanation to this Act, the expression “Attorney General” may include the Solicitor General. With reference to any other state, it is Advocate General of India.

There are two issues before the apex court as also before the AG. First, should we still use the draconian powers of contempt of court based on alleged “scandalisation”? Second, does complaining, by itself, become punishable for contempt? These questions are quite relevant as they might deter people from complaining, which is against spirit of scientific inquiry and critical thinking, essential components of free speech in a democracy.

Contempt not used in United Kingdom

There is an interesting incident on initiating proceedings against criticism. The British newspaper, Daily Mirror, published an upside-down picture of three law lords with the caption, “You Old Fools”. Advocates approached Judge Lord Sydney Templeman, requesting him to initiate contempt proceedings. He refused, saying he was indeed old and whether he was a fool was a matter of perception, though he personally thought he was not one. British judges took a very liberal view of contempt law and gradually declined to imprison so-called contemnors. They now prefer to use the law only to enforce judgments, but not to protect judges from criticism under the traditional head of “scandalous” contempt.

Consider against this background Upadhyay’s letter to Venugopal. He contended that the letter from the Reddy “scandalises” the authority of the SC and the HC and interferes with judicial proceedings and administration of justice. He said, “there are 31 criminal cases pending against the Chief Minister, with charge-sheets”.

As per existing laws, charge-sheeted accused are free to contest elections, until and unless they are convicted in a crime and punished. No political party is willing to change the law to prevent the criminally accused from contesting, as they do not want to refrain from fielding criminals in elections.

Who is Upadhyay?

Upadhyay has filed several PILs which are prominent on the BJP’s political agenda, such as on yoga, Vande Mataram and nikah halala. He filed a PIL in the SC challenging the constitutional validity of Article 370. In 2016, he filed a PIL before the SC seeking special courts to decide criminal cases involving legislators in one year; so that convicted persons are barred from contesting elections.

On 16 September, a bench headed by Justice Ramana asked HC Chief Justices to constitute a special bench to monitor progress of criminal trials against sitting and former legislators, and to “forthwith” list all cases which have been stayed, and decide whether the stay should continue. Interestingly, on 9 October, a case of disproportionate assets against Jagan Reddy commenced before a CBI special court in Hyderabad, in pursuance of the Supreme Court’s directions. The very next day, the CM’s Principal Advisor released to the media Jagan Reddy’s controversial 6 October letter to the CJI. The letter alleges that Justice Ramana “has been influencing the sittings of the (Andhra Pradesh) High Court including the roster of few Honourable Judges”.

Now, in his own filing, Upadhyay had said, “...if this kind of precedent were allowed, political leaders would start making reckless allegations against judges who do not decide cases in their favour and this trend would soon spell the death knell of an independent judiciary.” He then sought consent under Section 15(1)(b) of the CCA, 1971, read with Rule 3 of the Rules to Regulate Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court, 1975, to initiate criminal contempt against Jagan Reddy, and Ajeya Kallam, the advisor to the Andhra Pradesh government.

Upadhyay claims that the actions of these two individuals constitute grave criminal contempt of the SC and the Andhra Pradesh HC. Upadhyay said he decided to take up the issue because although Jagan’s letter had been in the public domain for around two weeks, the SC had not initiated action.

Significance of AGI

The AGI is a constitutional office which is expected to exercise its discretion in considering requests for consent, without which proceedings cannot take off. While considering such applications, neither the AGI nor the Advocate General of a state are to act as advocates on behalf of the Union or states, respectively. Hence, the decision is not an “opinion” expressed by the AGI, and cannot be considered an instruction of the government either.

The present AGI is an expert on constitutional law and a statesman. A well-read, highly experienced nonagenarian, he has received the Padma Vibhushan and Padma Bhushan.

Analysis of AG’s letter

The AG said the “timing itself of the letter, as well as its being placed in the public domain through a press conference could certainly be said to be suspect, in the background of the order passed by Justice NV Ramana dated 16 September 2020 directing pending prosecution of elected representatives to be taken up and disposed of expeditiously”. Venugopal described the conduct of Jagan Reddy and his advisor as “prima facie contumacious”, that is, stubbornly or wilfully disobedient to authority. This is indeed a very serious comment. He also found objectionable that they had placed their allegations against the judiciary in the public domain. Ye, finally, the AG declined consent for contempt proceedings against them saying that the CJI, SA Bobde is “seized of the matter”. Nowhere has the AG said that these acts would amount to “contempt of court”, though he found them objectionable and disobedient to authority.

It is important to remember that refusing consent does not imply a “clean chit” to either Jagan Reddy or Ajay Kallam, or vice versa. The timing of writing the complaint, in the wake of the SC Bench’s order for speedy trial of criminal cases where political leaders were charged, makes, “prima facie, the conduct of the said persons...contumacious,” is what Venugopal said. He also said, “...the entire case of contempt arises out of the letter dated 6.10.2020 written by the Chief Minister directly to the Chief Justice of India and the subsequent press conference held by Shri Kallam. The Chief Justice of India is, therefore, seized of the matter, Hence, it would not be appropriate for me to deal with the matter. For these reasons I decline consent to initiate proceedings for criminal contempt...”

There are several reasons why it was appropriate for the AG to not have given his consent. One, Jagan Reddy’s letter is basically a representation and request. It may also be considered a complaint because of serious allegations it makes. The theme and scheme of our constitutional system and the mechanism devised by the SC has provided for examining or testing the veracity of allegations mentioned in any complaint. At this stage, there is no scope for believing the allegations against Justice Ramana, and it in no way obstructs his elevation to CJI, as per his seniority.

In fact, stakeholders in the judiciary should be interested in getting his name cleared of these allegations and believe that these complaints cannot cause any harm to the credibility of the judiciary and the faith reposed by people in the institution of the SC.

It is believed that the CJI, to whom Jagan Reddy made the complaint, will have a free hand and reasonable time to consider it and act in his own discretion, according to the process adopted by the Supreme Court in 1999 and announced in 2015. Initiating contempt proceedings against the CM and his advisor at this juncture might obstruct that process. The rule of law and mechanisms of the SC envisage giving due consideration to and, thereafter, if needed, hearing out all complaints. Such a process would help the judge to emerge from any allegations with dignity.

Two, prosecuting or punishing a complainant for contempt of court, before verifying the allegations made in his or her complaint is not proper, reasonable or justified.

Three, the law of contempt of court should only be used for effective implementation and compliance with the judgements of the SC or other courts, and not for filing a complaint against a judge. If such complainants are prosecuted—instead of their complaints being examined—it might send a wrong message that the extraordinary powers of courts were being used to suppress complaints.

Four, the request for consent has been filed by a SC advocate who is also with the ruling political party, which commands an absolute majority in Parliament. Meanwhile, the complaint has also been filed by a chief minister, who is also president of a political party. In addition, the TDP (against whose leader Reddy makes charges) fought elections in 2014 as an ally of the BJP and in 2014, a partner of the coalition it leads has come to power in Andhra Pradesh. For some years, the TDP shared power at the Centre with the BJP. Hence, acting on the petition of a BJP leader will give political colour to this episode, which would come at the cost of neutrality and objectivity.

As the request has come from a BJP leader, both the acceptance and rejection of such a request might lead to several interpretations and speculations which could undermine the dignity of the judiciary. To be clear, the petitioner has every right to file such a petition, but accepting his request would be more harmful than the harm that might be caused by its rejection. In these circumstances, the AG has reposed confidence in the discretionary powers of the CJI and left it to his offices to decide on the letter.

It is not proper to politicise the complaint and contempt issues. Political parties should not use the forum of judiciary for their goals and interests.

Second rejection

In rejecting once again a repeat request from Upadhyay to punish the Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister for having complained, Venugopal has stuck to his earlier opinion that the CJI should be left free to exercise his discretion. The AG advised Upadhyay to approach the SC if he wishes. Can Upadhyay now file a Writ petition before the SC asking to invoke its contempt power on its own? To do so, however, would be a self-contradiction. How can another entity or individual ask an institution to “act on its own”? Upadhyay may submit a representation to the CJI in an ordinary manner, as the Constitution does not provide for a writ for this purpose. As already mentioned, unless one shows that his fundamental rights have been violated, the SC cannot entertain any PIL or another petition under Article 32. In Jagan Reddy’s complaint to the CJI, there is nothing that Upadhyay could lose.

The writer is a former Central Information Commissioner. Views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.