How Army Misuses Structural Immunity: 18 Years After Chattisinghpora Massacre, Pathribal Fake Encounter, Brakpora Shootings

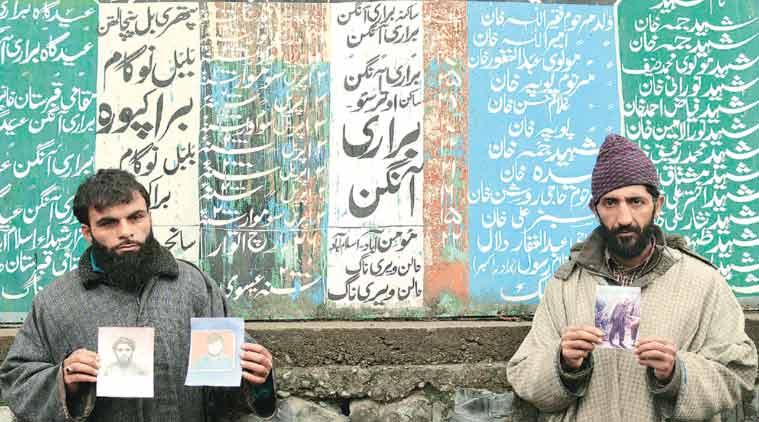

Protests on the 14the anniversary of Pathribal encounter. Image courtesy: Indian Express

Eighteen years ago today, on 20th March 2000, 36 Sikh men were shot dead in Chattisinghpora village of Anantag, Kashmir. This massacre took place during then US President Bill Clinton’s visit to India, the first visit by a US President in 22 years.

Five days after the incident, on 25th March 2000, Farooq Khan, the Senior Superintendent of Police of Anantnag, announced in a press conference in the presence of then Home Minister LK Advani that five “foreign militants” responsible for the massacre had been killed. The Army unit 7 Rashtriya Rifles in a “joint operation” with the Special Operations Group (SOG) of Jammu and Kashmir Police took down these “foreign militants” in the forests of Pathribal, also in Anantnag, it was announced.

However, in the two to three days before this “joint operation”, five men from the villages surrounding Pathribal had reportedly been abducted by either the army or police in presence of eyewitnesses. A day after the Pathribal operation, a villager saw the dead bodies of the alleged militants and recognised one of them to be Jumma Khan, one of the men who had been abducted earlier. It later emerged that all five who had been killed in the army’s operation were actually the men who had been abducted. Apart from being shot dead, the bodies of the five men were also burnt beyond recognition.

Following this incident that came to be known as Pathribal fake encounter, on 3rd April 2000, around two thousand villagers from the surrounding areas, including the families of those who were killed, came out in a peaceful procession to protest the extrajudicial killings and demand the return of the bodies to the families. When the crowd reached Brakpora Chowk, they were met by open firing by personnel from the CRPF and the SOG. Eight civilians lost their lives and thirty five others were injured. In a span of 15 days, 49 civilians were killed. But no family has received any justice.

The case of the Pathribal fake encounter is particularly demonstrative of the kind of legal immunity the army enjoys and misuses. Multiple investigations clearly established the fact that the encounter was fake, and it was seen as an attempt by the army to save face after the Chattisinghpora massacre.

After the families of the Pathribal fake encounter victims filed a petition, the bodies of the victims were exhumed for taking DNA samples to establish their identities. These samples were fudged twice. The case was then handed over to the CBI, under whom the analysis of the DNA samples proved that the bodies did in fact belong to the five local villagers and not any foreign militants. The chargesheet presented by the CBI in 2006 presented many other facts which challenged the army’s claim that the encounter was genuine.

Apart from the identities of the victims, one of the most indisputable findings by the CBI was that “the killed persons sustained about 98 per cent burn injuries in addition to the bullet injuries indicating use of excessive and unwarranted force. It is impossible for the killed persons to have suffered such extensive burn injuries in a genuine encounter. The encounter was stage managed with a view to obliterate the identity of the killed persons with an oblique motive.” They also pointed that the “hideout place” of the “militants” was barely burnt.

After CBI filed the chargesheet, the army approached the Supreme Court, which years later in the May of 2012 passed an order giving the army the option to choose how it wishes to pursue the trial, via a court martial or a criminal court. As the incident took place in the “disturbed” area of J&K, the Army Act allows the armed forces to avoid facing persecution by any criminal court even in cases of civilian offences. The Pathribal fake encounter was clearly not carried out under “active duty” and should not be tried by a court martial. But the current rules allow for this to happen.

The army chose the option of a court martial, but soon dismissed the proceedings as a case of no evidence. The army informed the chief judicial magistrate of Srinagar of this decision through a closure report, but failed to provide the families of the victims with any copies of proceedings which led to the investigations being closed at an initial stage.

The fact that the case was taken up through a court martial is problematic also because it allows the army to be a judge in their own cause. A court martial only has the capacity to pass action for disciplining army personnel and is not equipped to handle cases of human rights violations. In fact, a court martial is completely closed off to civilians for seeking any action.

The army’s decision to re-investigate the Pathribal case was also questionable as CBI’s chargesheet clearly showed that no dispute existed in the fact that the encounter was fake. The families of the victims approached the Jammu and Kashmir High Court raising these questions, and challenging the army’s decision to close the case. The petitioners also challenged the army’s decision of not providing a copy of the investigation proceedings. In a disappointing move, the High Court dismissed the petition.

While the High Court said that the army had the option of closing the case on grounds of no evidence since the Supreme Court had given them an option to hold the trial via court martial, it is important to note that the case never proceeded to the stage of a court martial. The army directly flouted the orders of the Supreme Court to hold the trial, and was able to terminate the case at the inquiry stage. But the army termed their process to be “effectual proceedings”.

With all other avenues closed, the families of the victims filed a petition in Supreme Court in July of 2016 challenging the J&K High Court’s dismissal. The petition raises some crucial legal questions, such as the fact that if a court martial is being used to terminate a case itself, then is this exercise of power not mala fide? Can this termination of the case be seen as “effectual proceedings”? If the Army Act, Army Rules, and Armed Forces Special Powers Act can be used to grant such immunity to the armed forces while directly violating the right of a citizen to a fair and impartial investigation, then are these army acts constitutional?

The plea was admitted in August last year, with the apex court issuing notice to the Centre, the Jammu and Kashmir Government, the army and the CBI, giving them six weeks to respond to the petition. The matter is still in front of the Supreme Court and is due to be heard on 8th May this year. After 18 years, justice still seems to be a distant sight.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.