Dry Day: Drinking Water Budget 2021 Falls Flat Again

Image Courtesy: Bloomberg

When the government returned to power in 2019, one of its first decisions was to merge the Ministries of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation into one ‘Jal Shakti’ ministry. It was a welcome move since the expectation was that more holistic water management would be now possible. The country is already neck-deep in a water crisis and moves such as these offered rays of hope.

The government also announced the har ghar nal se jal for rural India by 2024 and announced a commitment of Rs 3.6 lakh crore for the same. This was another welcome move, especially for rural women, who, for the longest time, had struggled for that elusive pot of water to quench the thirst of their family first and then their own.

Then began the wait for guidelines, and the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) guidelines were released in late December 2019. These guidelines outlined in some detail the objectives, the allocations for different areas and proposed a budget break-up for the financial years between 2019-20 and 2023-24.

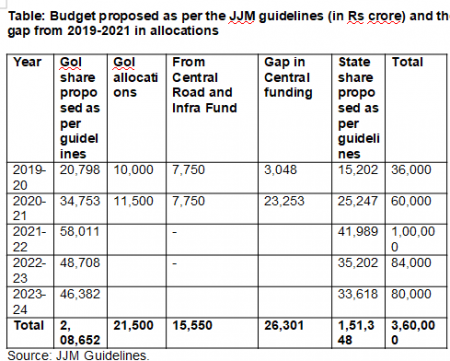

This budget breakup includes contributions from the Centre and State governments. As per the JJM guidelines, the contribution from the Centre is at Rs 2,08,652 lakh crore and contribution from the states was pegged at Rs 1,51,348 crore between 2019-20 and 2023-24. The guidelines also propose year-wise budget allocations.

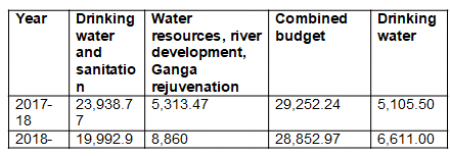

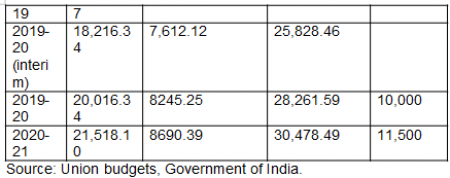

Just like the budget for 2019-20, this financial year’s budget for drinking water is disappointing. There was a marginal increase as compared to previous years, especially prior to 2019-20, when the budget for Swachh Bharat Gramin was increased, at the cost of a huge slash in the budget for drinking water. The budget allocated for drinking water still remains grossly inadequate when compared to the government’s commitment to provide every household with piped water supply—nal se jal—by 2024.

The table below gives the budget allocation over five years, as proposed in the JJM guidelines. The table also includes the actual allocations for 2019-20 and 2020-21. It highlights the gap so far.

The figures indicate a widening gap between requirements and the allocations by the central government. In just two financial years, this gap has already increased to Rs 26,301 crore. There is also a huge financial burden on the states to meet their growing financial commitment, from Rs 15,202 crore to Rs 1.51 lakh crore between 2019-20 and 2023-24, a ten-fold hike.

Allocation for the department of drinking water and sanitation under Jal Shakti Ministry (in Rs crore) still falls short of what was allocated to the Ministry of Drinking Water Supply in 2017-18 (see table below).

The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) Guidelines for rural drinking water

In December 2019, the government launched guidelines for the provision of household level drinking water supply in rural areas through the release of the Jal Jeevan Mission (har ghar jal or water to every household) operational guidelines.

These guidelines give details of various definitions such as the time-frame in which the target of har ghar jal or water at every household (2024) and the financial and institutional mechanisms for achieving the same.

One of the major objectives of JJM is the provision of FHTC or Functional Household Tap Connection to all rural households for the provision of adequate quantity of water—55 litres per person per day (lpcd) of prescribed quality on a regular basis.

The main components under JJM include (i) Development of in-village piped water supply infrastructure to provide tap water connection to every household (ii) Development and augmentation of existing water sources to provide long-term sustainability of the water supply system (iii) Bulk water transfer wherever required, treatment plants and distribution network (iv) Technological interventions for removal of contaminants where required (v) Retrofitting of completed and ongoing schemes to provide FHTCs at minimum service level of 55 lpcd (vi) Grey-water management and (vii) Support activities for IEC, training and capacity building, water quality laboratories.

The guidelines highlight the challenges faced by the drinking water sector which include the following (a) Changing rainfall pattern (b) Water quality issues (c) Inadequate infrastructure including absence of source sustainability measures (d) Poor operations and maintenance or O and M (e) Lack of resource efficiency (f) Less community involvement and (g) Coordination challenges.

Challenges

However, how the new guidelines will address these challenges is as yet not clear.

One of the biggest challenges faced by successive rural drinking water programs have been the redundancy of created infrastructure due to either lack of O and M or drying up of water sources. While the guidelines do mention the need for source strengthening, resources for the same will depend on convergence with schemes and programs from other departments and ministries. Some of the programs mentioned include watershed development, MG-NREGA, repair and restoration of water bodies and other such activities.

Reports indicate that almost 80% of surface water in India is contaminated and a growing percentage of groundwater reserves are contaminated with biological, toxic, organic and inorganic pollutants.

As in the past, these current guidelines also mention the setting up of water quality monitoring labs for testing the water quality and the service provider level and water quality surveillance through field testing kits which will be the community. The water quality labs will test the water for 13 parameters which include pH, hardness, alkalinity, turbidity, dissolved solids, sulphate, chlorides, iron, nitrate, arsenic, fluoride, E. Coli and total coliform bacteria. This is not even the complete list of contaminants to be tested as per the BIS 10500 specifications for drinking water. Report after report from the government and other sources informs on the alarming chemical contamination that is found in surface and groundwater sources, which includes pesticides, heavy metals such as chromium and even uranium.

With severe water-related challenges on one hand and inadequate financial resources to address these on the other, people may just be in for a rude shock.

The writer has worked for more than 20 years on water resources and is now associated with the Safai Karmachari Andolan and the Tarun Bharat Sangh. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.