BJP Turns to Digital Politics Amid Pandemic

Amit Shah's virtual rally for Bihar Assembly elections. | Image Courtesy: National Herald

It’s party time for the Home Minister. After a near-hiatus during the lockdown, he is back to doing what he loves to do for the party — fighting elections. It’s campaign season, with elections to the Bihar state assembly not too far off, and thus, it is expected that Amit Shah will be in his elements. COVID-19 has thrown a minor spanner in the works, but who knows, it might be blessing in disguise.

If the coverage of Shah’s first “e-rally” is anything to go by, corporate media will continue to play the fiddle, but this time, the second fiddle! The primary place where the conversation around the elections will take place will be the party’s digital platforms, with all the accompanying contradictions.

The focus is on the 72 digital rallies slated to be held in the run up to the elections in Bihar, but to satisfy its analogue existence, the Bharatiya Janata Party is going to release a 30-page booklet titled "Who is trying to weaken India's fight against COVID?" No prizes for guessing who. Yes, the Opposition!

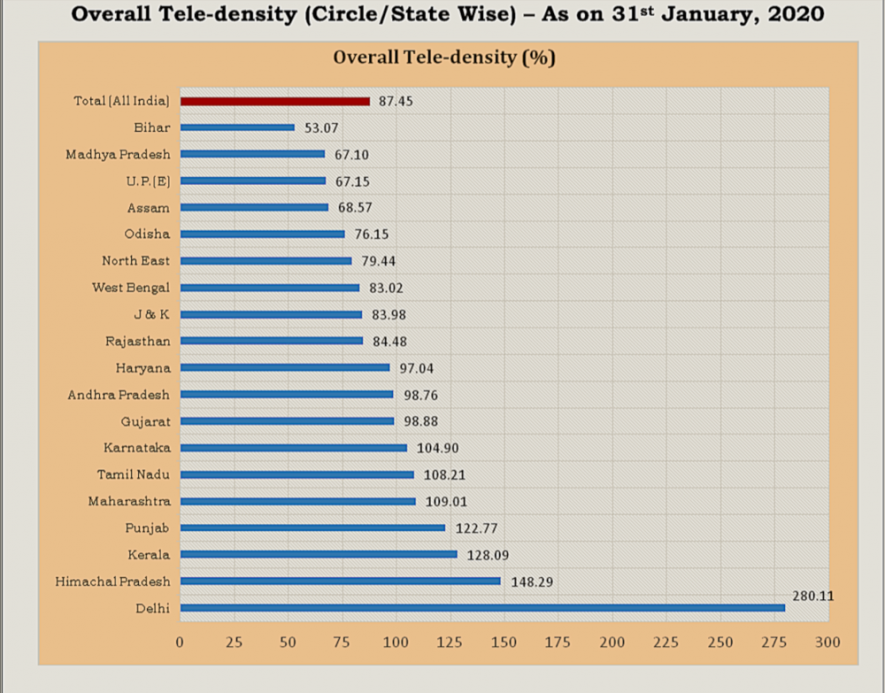

Bihar has the least tele-density in the country with just 53.07% wireless telephone subscribers in January 2020. With such poor tele-density, a digital-led strategy for the upcoming Assembly elections for a party with overflowing coffers still seems herculean, leave alone the fact that it has to face angry migrants who have had to trek hundreds of kilometres to Bihar. Mainstream media though can be expected to trot out the familiar “Shah is a Chanakya” refrain when it comes to winning elections and even when he doesn’t, knowing how to steal the mandate!

A pandemic calls for innovation. After all, there are the positives: the Times of India lists the benefits of having e-rallies in neighbouring West Bengal, thus: “Kolkata won’t be choked with rallyists, there will be no traffic jams and the blaring microphones. It will be economic too. While Shah connects with his audience through Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, the party will be spared of spending Rs 75-80 lakh needed for setting up the dais, the microphones and for getting people to the rally.” The BJP rivals in West Bengal may not be far behind, with the Trinamool Congress and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) also quite aware of the digital piece to counter the saffron juggernaut, but its rivals in Bihar might not see such merit in digital.

Hindutva’s early discovery of the virtues of getting online and using online tools has paid handsome dividends. What started off as an outreach programme by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its affiliates to attract diaspora Indians, especially in the United States, has morphed into a well-oiled machinery with the emergence of social media that has served them well to keeping a willing audience enthralled.

But to elevate digital to the status of the most effective tool to win elections does not even merit a tête-à-tête, leaving alone a discussion. The BJP, aided by it progenitor, has built up a formidable network of workers to work during elections. Despite it’s current bloat, the BJP does boast of a cadre, people that are called “panna pramukhs”, a la Mr Bhat, the likes of whom are expected to be in “constant touch with the 60 voters he was assigned to track for the party”. Journalist Swati Chaturvedi’s I Am A Troll showed the even seamier side of the operations. Despite that, recent election results have shown that the party has not had it easy.

Also watch: BJP Likes 'Only' Elections

Beyond the cadre and the moneybags is what a former data analyst of the BJP said to Caravan: “The BJP’s strategy with respect to elections is that if you win the booth, you will win the constituency, and the state.” The infrastructure around elections for the party now involves not just teams of data analysts but even graphic designers and video editors, outsourced to groups to handle allied social media pages and handles and researchers.

An emaciated Congress and all the Opposition put together is incapable for matching the digital prowess of the BJP. This isn’t about some congenital ingenuity of rightwing cadre, but just that platforms such as Google, Facebook and Instagram have been proven to have a rightwing bias.

But what’s important is how during a pandemic, the country, vacillating between lockdowns and “unlockdowns”, will witness the transformation of political parties into largely backroom operations, and likely to mimic digital newsroom operations of corporate media houses.

The BJP’s digital portfolio includes a website, a Facebook page along with a panoply of pages for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the party president JP Nadda and some state units. The panoply extends to Twitter handles, Instagram pages, a mobile app and a Youtube channel. This suite of social media distribution channels belong to the standard arsenal of any newsroom. The pandemic has led to virtual press conferences too.

WhatsApp, by its excellent returns on investment, has been considered a separate beast. If it wasn’t for the limitation imposed by the product, the medium offers the best mode to distribute content that has served the party’s larger agenda well. With the addition of WhatsApp to the arsenal, not just the BJP but many political parties have become veritable gatekeepers of content, although the saffron outfit, for reasons not limited to production capacity, is by far superior in being a prolific purveyor of content. The Congress party, with its rather dispirited bunch of workers has been making efforts to counter the BJP’s firepower. The Left parties too have been active online and have been able to punch way above their capability, thanks to the surfeit of goof ups by the ruling dispensation. Bihar poses a unique challenge to reach out to people digitally, with the worst infrastructure in the country. However, the political parties vying for the state have little choice this time come elections, given that they have to campaign during a pandemic with all its restrictions on people gathering together in large numbers.

Digital campaigns in Karnataka, for instance, could be a better draw. If Bihar’s tele-density is poor, Karnataka’s is a whopping 104.90%. So it makes sense that the ruling BJP announced its first virtual rally - Samartha Nayakatva — Samartha Bharatha — to be held on June 14. Apart from Chief Minister BS Yediyurappa, the BJP’s national general secretary (organisation) BL Santosh and the state president of the party Nalin Kumar Kateel are to participate in it. Not to be left behind, DK Shivkumar, the freshly anointed state party president of the Congress is to have a virtual display of his swearing in, named Prathijna Dina.

Also read: Digital Monopoly Platforms, Modi Regime and Threat to Our Democracy

Karnataka Deputy CM Ashwath Narayan might still insist that the logistics of real-world campaigns are the challenge. Talking to the Times of India he said, “For a huge political rally, parties must spend huge money on hiring helicopters, chairs, flag makers, stage decorators, hotel stays, cars, buses and trucks, besides food, but for a virtual rally, the party hardly needs to spend anything.” He will, however, soon realise that virtual campaigns for the upcoming gram panchayat polls can be “better” monitored with analytics, which might come back to bite him.

Sayantan Ghosh, the BJP Bengal state unit general secretary, speaking to the Times of India said that it would be difficult to gauge the mood. But he did acknowledge that in social media he could gauge it by looking at the “views”, quite like how he would for broadcast look at the TRP ratings. But he does recognise the challenges too, “For instance, a couple may watch Amit Shah on Facebook. But the count will be one instead of two.”

Reports might be generated easily to know the time spent, the percentage of people who stayed on till the end, the number of people who “interacted”, the number of new people who joined and so on. These metrics will be the basis on which the performances of leaders like a Narayan or a Ghosh will be judged.

This is new terrain for analogue politicians. If half the population does not own a smartphone, a smart TV or any other digital paraphernalia, then how can they be reached? More importantly, how can they be counted, assuming they can be convinced? Political activists would thus have to create social media accounts and go around not just distributing them, but also ensure that people log in, and also do a good cut-and-paste job in the comments section!

The fine art of political communication has come a long way from a speech exquisitely delivered to a field full of people. It has moved from there to targeting communications on social media knowing the voting preferences of people, generating content and controlling its distribution, to now having to actually do the “groundwork”, mobilising and delivering rousing speeches on various platforms, each with their own idiosyncrasies and strength.

The pandemic has opened up a whole new vista of digital political communication.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.