Not Urban Sprawl, Neglect Worsens India’s Covid-19 Crisis

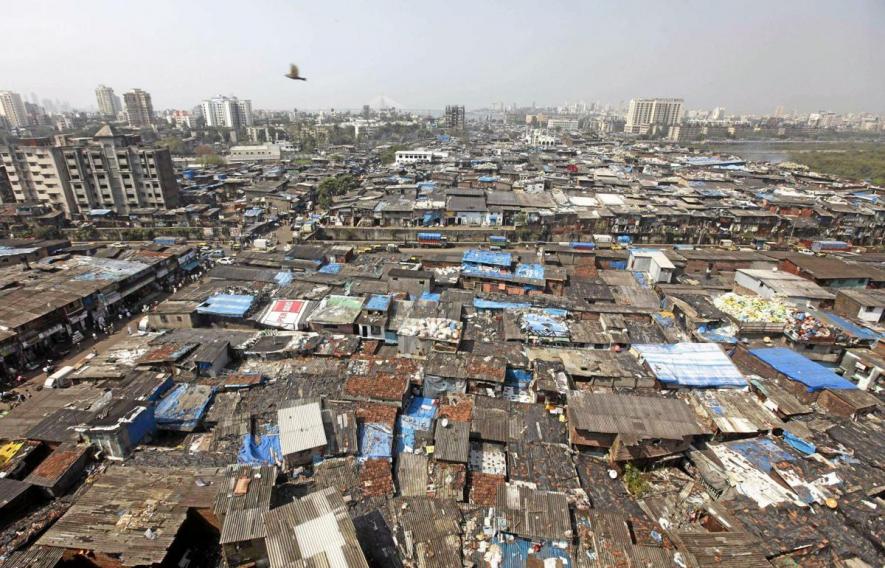

The spread of Covid-19 in Maharashtra provides an opportunity to study the spread of the pandemic in India’s urban clusters and the reasons for it. So far, Maharashtra has the highest incidence of Covid-19 cases in India, and within it, Govandi and Mankhurd in the M-East Ward of Mumbai are among the worst-off sub-regions. These two parts of Mumbai comprise some of the densest urban sprawls in the country. Late last month, these two zones of Mumbai also reported the highest mortality rates from the disease, at 9.7%.

What do Mumbai residents, who are watching the situation unfold, think about this? Do those who are providing relief to the worst-hit zones, and doctors, have ideas about the reasons and solutions? After all, tackling a pandemic in over-crowded zones is a challenge for governments across the country. I spoke to Fahad Ahmed, a student at the School of Social Work at TISS, Mumbai, who has been distributing ration in the slums of M East ward. He says, “It is for a reason that this area is called a gas chamber. The Deonar Landfill, Asia’s largest dumping ground is located here.”

The century-old Deonar dump is barely two kilometres from Govandi and Mankhurd and accepts a quarter of Mumbai’s total solid waste. It was supposed to stop accepting more waste after December 2019, but in January the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) filed an affidavit in the Bombay High Court seeking an extension until June 2023. It is only by then, the civic body said, that it would be able to construct a waste-to-energy plant at the site.

The problem of waste management and its connection with disease is neither new nor just Mumbai’s problem. However Covid-19 has brought the question of sanitation to the fore, along with other other equally serious issues. For instance, the Novel Coronavirus spread rapidly in the old city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, to the dismay of residents of Bapunagar, Gomtipur and Dhorwada, where most of the working class live. Dev Desai, a human rights activist and trustee of Anhad, a socio-cultural outfit, is supplying rations some of these areas. He says that the number of cases in Gujarat has been climbing due to the weak health infrastructure—and the poorer neighbourhoods in Gujarat’s cities are the worst-affected. A week ago, of the 520 positive cases reported in Gujarat on a single day, Ahmedabad accounted for 330 cases of Covid-19. A few days later, the highest number of cases reported in Gujarat on a single day touched 580 and on 22 June, 563 new cases were reported. Overall, the number of cases in Gujarat is well past 25,000.

The problems faced by residents of the crowded clusters in the state are compounded by the dismal condition of its public hospitals. “The pandemic has been with us for nearly six months, yet 65% of doctor, nurse and para-medical staff positions in government hospitals are vacant,” Desai says. “Where would the poor go for treatment? We are in an extremely challenging situation because of the unavailability of medical help,” says Desai.

Prof Hemant Shah, who teaches economics at the HK Arts College in Ahmedabad, says that the medical staff in government hospitals has stopped work four times during the pandemic because they are not getting their salaries. “The lack of medical care explains why Gujarat has such a high fatality rate even when the number of patients are low,” says Shah. This was true even in April, when the pandemic was yet to bare its fangs in India. As the Ahmedabad Mirror had reported on 3 April: “Against the total 88 corona cases in Gujarat, seven deaths were reported till Thursday [2 April], while Maharashtra which leads in the country with 335 cases, 13 death cases were reported.”

And the Capital city is rapidly catching up with Maharashtra in terms of total infections. Here too, the residents of crowded areas are bearing the brunt of the pandemic. There are 675 over-crowded and under-developed clusters in Delhi, of which Bhalswa and Jahangirpuri report very high incidence of the infection. The lack of sanitation and healthcare has an added dimension in Delhi—the shocking refusal of hospitals to accept patients of any kind.

Surekha Singh, a co-ordinator for the NGO Action India for Seemapuri, Janata Mazdoor Colony and Sanjay Colony, says, “While Covid cases in these clusters are high, a large numbers of residents also suffer from non-Covid ailments such as cancer, heart disease and epilepsy. Hospitals keep turning such patients away saying they are full—not that getting admission as a Covid patients is easy.”

Seen in this light, Indian states have responded to the Covid-19 crisis with some ameliorative interventions, but their response lacks an overall strategy. The problem is not just the crowding or lack of facilities—it is also that even in the known hot spots both sanitation and healthcare have been neglected despite the high fatalities.

For instance, to return to Mumbai, it has already tried out four containment strategies. “We have had testing, no testing, contact tracing, no contact tracing. This is hardly how to fight a pandemic,” says Rais Sheikh, a Samajwadi Party legislator who is doing relief work in M East Ward and Bhiwandi.

Aditi Anand, a volunteer and film-maker who is helping raise funds for Dharavi Diaries, an NGO engaged in relief work, says that the problem is compounded by how exhausted the BMC staff in Mumbai are getting. “The pandemic has gone on for long and they need to hire more people. This exhaustion is not a good sign, since we are still in for a long haul,” she says.

The silver lining is that Dharavi in Mumbai has reportedly turned a corner. This urban sprawl had earlier recorded a fatality rate of 4.1% compared to the 8.2% average fatality rate of Mumbai. The death rate in Dharavi had zoomed, but now it is said to have declined to 1.02%. Dharavi has a population density of 2,27,316 persons per square kilometre, and has reported over 2,000 positive cases. However, some 5 lakh Dharavi residents were screened, fever clinics were set up, and the infected moved to Covid-care centres.

But this model is obviously not being replicated across the city, forget the country. “Not enough sanitisation work is being done. Hospitals have become overcrowded and it is very difficult for Covid patients to find a bed,” says Anais Shaik, a resident of Dharavi. Testing in some of the densely-populated clusters of Mumbai has virtually reached an impasse. This is the exact opposite of the strategy adopted in Dharavi early on, which seems to have paid off despite setbacks such as the migrant worker’s crisis.

“[The problem is that] we are only reporting those cases where hospitalisation is required. Community tracing has been completely stopped. Everyone here is upset with the loss of livelihood. People want industries to start so that they can get back their livelihoods,” Sheikh says.

But Dharavi also tends to capture attention in a way that other slums, whether in Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad or elsewhere do not. More than making examples of a chosen few hot spots, India’s cities need a strong overarching narrative and effective local leadership to tackle this crisis.

“We need strong local leadership at the community level [too] so that the poorer can access resources that are allocated for them,” says Akhila Sivadas, who heads C-FAR, an NGO that has helped six lakh families access their ration entitlements during the pandemic. Sivadas believes that the central government must shed its adversarial attitude towards NGOs. “We [NGOs] cannot match the resources of the government. For instance, Bengaluru has 200 wards while we are present in five of them. But we can offer on-ground knowledge since our workers belong to these communities,” she says.

Doctors, too, believe that states must implement “bullet proof containment” strategies. Dr Monik Mehta, a cardiologist with Columbia Asia Hospital in Gurgaon, Haryana, close to the national capital, is a votary of the Bhilwara model for all containment zones. “Easier said than done, given the large number of containment zones we have. Delhi alone has over 240,” he says.

Bhilwara in Rajasthan is one of the earliest hot spots of Covid-19, but is known to have controlled the pandemic by ensuring people were provided basic needs such as healthcare and access to food. It also credits a better communication strategy for getting people to support some containment strategies that entailed hardship.

But easier said than done indeed, for just this week, it was reported that Hyderabad in Telangana has 1,100 containment zones and that the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) has all but thrown up its hands in despair. The reason being cited is the lack of coordination between the municipal authorities and the state government’s health department as cases zoom. On 23 June, Telangana reported 872 new cases on a single day, of which 713 were in Hyderabad. “The Director of Public health said that 3,189 samples were tested in the 24-hour-period between 5pm on Sunday evening and Monday evening. Of the samples collected, 2,317 came negative while 872 tested positive,” another report says. Coordination and communication is said to be a critical part of the Bhilwara model, and yet, months later, cities are struggling to get it right.

India has a total 4,41,924 Covid-19 cases and the death toll has crossed 14,000. At least 60% of the positive cases have been reported in just seven metros, where 40% of India lives. Since the strike rate is much higher in them, they need better facilities, especially clean water, face masks and sanitisers. There is an immediate need for relief on these counts, or Unlock-1 will only lead to more viral infections, perhaps making the fear of yet another round of lockdown come true.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.