India’s Digital Divide: Who Faces it and How Wide is it?

Image Courtesy: Microsoft

The last four months have revealed that the government played the role of a bystander while the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing crisis unfolded. Be it implementation of the lockdown or pulling up the economy through fiscal expenditure, the central authorities failed to deliver any desirable outcomes. However, when the government attempted to be active—as when the University Grants Council (UGC) and Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) recently decided to restart the academic calendar—it revealed an inherently exclusionary attitude towards a large section of the population.

The UGC released a circular on 6 July that all final semester (or year) students must appear in a mandatory examination. As lockdown measures are in place in several regions, the mandated circular also indirectly implements the plans for online examination. Progressive student organisations have protested against this move, correctly saying that it will further exclude the marginalised sections.

We look here at the data that demonstrates the magnitude of exclusion that would ensure if the mandatory online examinations are put into practise in the current scenario. We find that it would reinforce the existing social exclusion of the marginalised sections: those living in rural India in general and students who belong to Dalit and Adivasi families in particular.

Forgetting the rural in education:

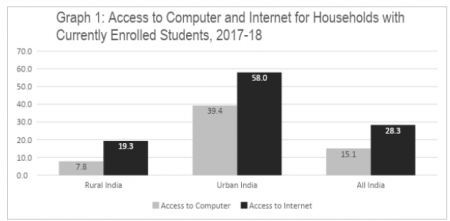

The Indian economy and the population engaged in economic activities within it are predominantly rural. The most reliable source of the magnitude of the population by residence, the Census of India 2011, reports that 69% of the population lives in rural areas. A similar share is seen for rural households that have at least one member enrolled as a student in any academic institution. The NSSO’s 75th Round of Surveys, on Social Consumption in Education for 2017-18, suggests that 76% of households which have at least one student as a member is from rural India. Yet as we see in graph 1, rural India has disproportionately low access to computers and internet services.

An abysmally low proportion of rural households which have at least one student enrolled during 2017-18 had access to the internet or a computer. When compared with urban households, rural students have three times lower access to the internet. Also, if we take a quick look at the all-India figures, only 28% of households with a currently enrolled student have any internet access.

The lockdown has limited travel options and the pandemic poses a high risk of contracting Covid-19 while travelling. Therefore, at this time, at least 70 to 80% of current students will have no internet access at all. This is the true picture of the digital divide—the probable exclusion of 80% of rural Indian students.

UGC’s “merit” discriminates against Dalit-Adivasi students:

Rural India has remained a space of persistent inequality and oppression. This is visible in every measure of well-being. The sources of such inequalities are different across regions, although social group identities, caste and tribe in particular, are often cited as a primary source of sectional deprivation and oppression. A study report by the Foundation for Agrarian Studies titled “Child Wellbeing, Schooling and Living Standards: An Overview of 14 Villages Across Six States of India”, discusses these aspects in detail.

On several occasions, the lockdown revealed caste-based brutalities and the character of state negligence in India. Education, for thousands of Dalit and Adivasi students in rural India, is a means to achieve social recognition. This progression has been marred with exclusionary tendencies from the elite caste groups. The move towards a universal online teaching and examination system affects the marginalised caste groups in two specific ways. First, their access to the means of participation in online education is terribly low, especially in rural India.

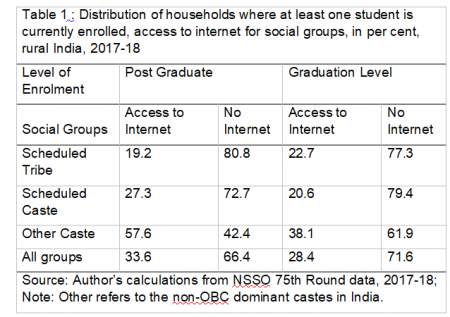

At the level of access, therefore, the digital divide will hurt the poorest sections most. Table 1 displays how access to the internet and other digital means of education is unequally distributed across social groups in higher education.

Out of 100 Scheduled Tribe households where at least one graduate student was enrolled during 2017-18, only 23 households had any access to the internet. The same statistic is 20 for Dalit households in rural India. When we compare this with the other (or dominant) caste households, we see a higher incidence of access to the internet at both graduate and post-graduate levels. The UGC circular, if implemented, will hence affect the Dalit and Adivasi students at the level of access to education most.

Second, the lockdown has unleashed a brutal livelihood crisis for the working class in rural India. The absolute loss in gainful employment for the landless manual workers in India has hit Dalit and Adivasi families in the countryside the worst. To impose yet another cost to attain education for the students from poor working-class families is atrocious at the least. Thus the UGC’s move to complete the remaining academic calendar through mandatory online exams enforces a kind of casteist practice, where a so-called merit evaluation is being done—something India has been doing for centuries as a means to exclude the marginalised from sources of learning.

For a long time, a vicious cycle of economic deprivation and lowered participation in education have excluded most of the marginalised from academia. Now, new measures are being put in place to reinstate the existing fault-lines in the realm of education in rural India.

Excess burden on female students during lockdown:

A peculiar and particular set of patriarchal norms prevail in Indian households, where it is largely left to the female members to “mobilise and allocate the labour and resources required to achieve human survival and well-being”, as Smriti Rao recently argued in her essay, “Lessons from the Coronavirus: The socialization of care work is not ‘just’ a women’s issue”. The particular form of labour associated with care work, or in a Marxist sense the “labour of social reproduction”, has burdened female members of households. Along with the biological reproductive burden, an extensive amount of work in the form of cooking food, cleaning the house or premises, collecting fuel, water, and other essentials, falls on women’s shoulders too, and often restricts their participation in education.

The NSSO’s 75th Round Survey on education suggests that in rural India, of every 100 female students who drop out of secondary school (class 10), twenty do so because they are engaged in domestic activities. This particular burden, seen in the current context of higher educational policies, reveals two concerns. First, increased care work within households burdens rural women and limits the scope for their educational pursuits.

Second, once this limited scope is coupled with the additional requirements posed by the online mode of education, the gendered outlook within families will tend to encourage more women to withdraw from enrolment compared to their male counterparts. Thus, unequal access to education and the intense burden of social reproductive labour together pose a threat to rural women.

Breaking the divide:

The current regime practices a particular form of political oppression of the marginalised. In their study of the criminalisation of victims, “Innocuous Mistakes or Sleight of Hand? Labour Law Changes”, Atul Sood and Paritosh Nath argue that the new norm among India’s ruling class is to deny labourers their labour rights, to brand political activists and jail them for violence that is in fact unleashed by the state, and now, finally, we see an attempt to exclude the already marginalised through “education policies”.

For a long time, the current regime has attempted to push higher education into becoming a privatised corporate-run entity. The New Education Policy, drafted and circulated in 2019, clearly takes away the public nature of education and makes it a marketable commodity. Now, through CBSE, MHRD and UGC circulars, a clear pattern of enforcing normalcy—at the cost of excluding a majority of students—is visible. Whereas the alternative, which would address the existing inequalities, only needs a political will. Kerala has successfully distributed lakhs of television sets and other aid materials to the marginalised and poor, and in a matter of weeks, to help with the shift towards digital learning.

Any attempt to bring “normalcy” into the academic calendar should address these existing inequalities first. One should never forget that no matter how romantic the “home-schooling” videos of celebrity kids might appear, to the biggest section of this country, they remain a portrayal of how the denial of their educational rights is being pursued in the guise of online education.

Tinanjali Dam is a PhD candidate in Economics at Christ University, Bangalore. Soham Bhattacharya is a PhD scholar at Economic Analysis Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Bangalore Centre. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.