Bolivarian Healthcare: An Alternative to Neoliberal Healthcare

On 23 September 2020, during the general debate of the 75th session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro said, “Neo-liberalism suffocated the public institutions, turning the rights of the people into private services; health became a luxury…The health and well-being of the population are not merchandise; the market cannot continue to regulate the destiny of humanity!”

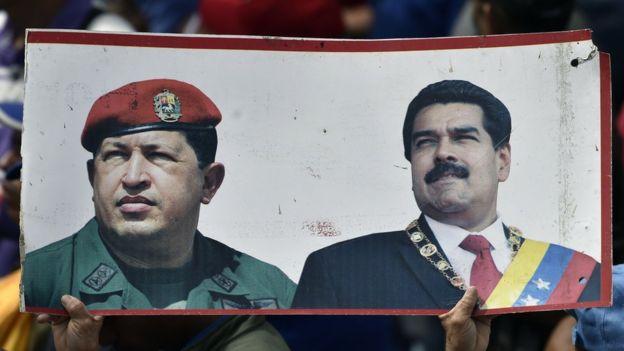

The criticism of the state of healthcare in the age of neo-liberalism is extremely important. It underscores the astonishing fact that the economic system we live under is incapable of fulfilling our elemental needs and demands exorbitant sums of money for something on which our sustenance depends. Venezuela is an alternative to the oppressive reality of capitalist healthcare. With the help of the Bolivarian Revolution, the Latin American country mapped a new socialist trajectory under Chávez, based on radical hope, dignity, and a sense of justice.

Neoliberal Catastrophe

Before the ascendance of Chavismo to power, Venezuela was marred by innumerous instabilities. The failure of policies intended to promote an equitable distribution of oil-generated earnings, the increase in the national debt, and a fall in oil revenue during the 1980s contributed to a socioeconomic crisis, which forced 54% of the population to live in poverty by the end of 1989. That year, Carlos Andrés Pérez was elected president for the second time following a campaign in which he promised the return of the economic explosion experienced in the 1960s, during his first presidency.

Instead of working for the poor, Pérez eagerly followed the dictates of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Both the institutions outlined a new plan “El Paquete”—an austerity scheme involving a profound reduction in public expenditure, privatisation of public enterprises, increased opportunity for oil exploitation by foreign parties, and liberalisation of commerce. These policies quickly faced extensive popular opposition. Subsequently, Pérez was removed from power in 1993 following a corruption trial.

This same period saw the decentralisation of a broad network of existing public services, with control passing from the national government to some regional governments. This heightened the fragmentation of health services and considerably weakened what remained of their effectiveness.

After a transition government lasting approximately one year, Rafael Caldera, a Christian Democrat, won the 1993 presidential elections, promising not to continue the neoliberal policies. In practice, however, the opposite happened, with the focus on a plan known as “Agenda Venezuela”, which followed the austerity recipe. In the health sector, the Venezuelan government obtained two loans, one from the World Bank and the other from the Inter-American Development Bank, both aimed at increasing profit-hungry private capital. The decentralisation of health services, combined with the austere fiscal measures of the early 1990s, left the responsibility for the management of poorly equipped health facilities to structurally wobbly regional governments.

The neoliberal health reforms instituted by Perez and Caldera in the 1990s ended up an unmitigated disaster. There was a fiscal reduction of public health services and the decentralisation of health services. When poorly financed and managed health services were decentralised and handed to regional authorities, they proved to be extremely inefficient. Consequently, it paved the way for greater privatisation of health services and institutions.

For those health services that remained under public authorities after widespread privatisation efforts, cost recovery mechanisms—users pay for services rendered—were introduced. The result of these changes was that by 1997, 73% of the total health expenditure in Venezuela was private. The privatisation of health services enormously expanded class-based health disparities.

It was in the context of neoliberal policies, with two-thirds of the population living in poverty or extreme poverty, coupled with a dramatic fall in oil prices, that Hugo Chávez was elected president of Venezuela in December 1998. This victory was the political conclusion of two decades of increasing popular mobilisation against corrupt Venezuelan regimes and the suffocating neoliberal formula.

New Constitution

The first political act of Chávez was the announcement of a public referendum so that the people could decide whether or not to call a National Constituent Assembly (ANC), mainly to write a new Constitution and construct the foundations for a new regime. On 2 February 1999, the president decreed the date for this referendum.

The decree included the following as the justification for his request, “The Venezuelan political system is in crisis and the institutions have undergone a fast process of de-legitimisation. Despite this reality, those benefited by the regime, characterised by the exclusion of large majorities, have blocked, permanently, the changes demanded by the people. Because of this behaviour, the popular forces have been unleashed, and would only have their democratic aspirations met through the call for a constituent founding power. In addition the consolidation of the ‘estado de derecho’ [rule of law] demands a judicial base that allows for the practice of a social and participatory democracy.”

The referendum took place on 25 April 1999, and 81.9% approved the call for an ANC aimed at transforming the state and creating a system for the effective implementation of social and participatory democracy.

Healthcare for All

The Bolivarian Constitution radically revamped the marketised conception of health. The health articles in the constitution are as follows:

- Article 83: “Health is a fundamental social right, duty of the state, which will guarantee it as part of the right to life. The State will promote and develop policies oriented towards the increase in life expectancy, the collective well being, and access to services. All individuals have the right to health protection, and the duty to actively participate in its promotion and defense, and to follow the health and sanitation measures that the law establishes, according to the International Treaties and Agreements signed and ratified by the Republic.”

- Article 84: “To guarantee the right to health, the State will create, lead, and manage a public, national health system, intersectoral in nature, decentralised and participatory, integrated with the social security system, directed by the principles of gratuity (free access), universality, integrality, equity, social integration, and solidarity. The public system will give priority to the promotion of health and the prevention of diseases, ensuring prompt care and quality rehabilitation. The public services and goods are propriety of the State and cannot be privatised. The organised community has the right and duty to participate in decision-making about planning, execution, and control of specific policies in the public health institutions.”

- Article 85: “The financing of the public health system is an obligation of the State, which will integrate fiscal resources, mandatory social security contributions, and any other source of financing mandated by law. The State will guarantee a health budget that enables it to implement health policy objectives. In coordination with the universities and research centers, a national human resource development policy to educate professionals and technicians, and a national industry to produce health inputs will be developed. The State will regulate the public and private health institutions.”

From the laws, we can observe that the Constitution undertook profound changes in the health sector. It reversed what was popularly known as Caldera Laws which had favored privatisation of the health system and implemented a variety of strategies to create a new health system. These included the implementation of integrated health care, a focus on primary health care centers, and preventive rather than curative care. However, the most significant change was the de-commodification of healthcare--the transformation of health services from a privilege enjoyed by the elitist few to a fundamental right of everyone.

On 15 December 1999, in a referendum for Venezuelans to give their opinion about the new Constitution, 71.37% voted in favor of the right to health.

Barrio Adentro

In the initial years of Chávez’s administration, one local jurisdiction in Caracas, Libertador Municipality, faced pressing problems in some of its poorest neighborhoods (barrios). As a result, Libertador, which was aligned with Chávez, created the Institute for Endogenous Development (IED) in 2003. IED was established to implement social programs aimed at empowering the poor. Sociologist Rubén Alayón collaborated with community workers to survey barrio residents on the various problems they faced--housing, health care, education, food security, and employment.

Residents identified healthcare as their greatest concern and detailed barriers to obtaining medical treatment. IED presented the information gathered to Freddy Bernal, mayor of the Libertador Municipality, who issued a call for physicians to live and work in poor neighborhoods. Fifty Venezuelan physicians responded, but they declined to live in barrios (30 left immediately upon learning that they would be required to live in barrios; the remaining 20 participated but were assigned to provide secondary care and thus were not required to live in barrios).

Remembering the Cuban doctors who provided emergency care after the mudslides of 1999 and remained as health care providers in some neighborhoods, Bernal initiated discussions with the Cuban Embassy that yielded an agreement to bring to Libertador a group of Cuban physicians who would provide the clinical services needed for the creation of what came to be known as Plan Barrio Adentro.

When the first 58 physicians arrived in April 2003, they were placed in homes and used the same space as a living area and examining room. Two additional groups of physicians followed. Health committees accompanied physicians on afternoon house-to-house visits--meeting families, assessing health needs, treating patients, and conducting censuses--as well as on emergency house calls. Committees assumed active roles in encouraging prevention, enhancing health infrastructures, and procuring resources.

In September 2003, after the pilot program had been evaluated and considered a success, Chávez named the program Misión Barrio Adentro and converted it into a national plan. It was defined as an initiative aimed at satisfying the constitutional requirement of health as a social right through a public health system. Ideologically, it was supported by the principles of equality, universality, accessibility, solidarity, cultural sensitivity, participation, and justice.

Barrio Adentro met the needs of 80% of the national population who had been marginalised and excluded by the old medical institutions and more than 75% were satisfied with the service according to the National Statistics Institute (INE).

Need for Socialism

In a 1966 speech to the Medical Committee for Human Rights, Martin Luther King Jr. declared: “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems that the world has not learned a lesson regarding inequalities in healthcare. Without the end of capitalism, no movement toward a just healthcare system can take place since the profit-maximising impulse will always impede any such attempt. What is needed, therefore, is socialism, which ensures that people are placed over profit.

The author is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.