Caste in Indian Cinema, Satyajit Ray to Mari Selvaraj

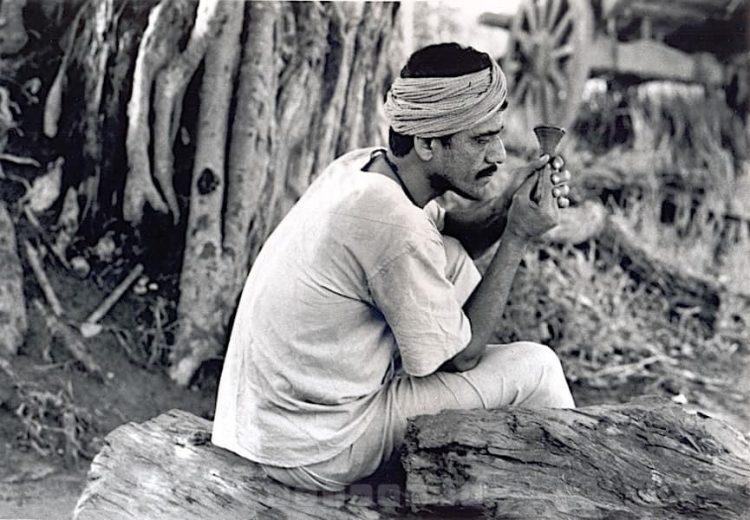

Om Puri as Dukhia in Sadgati, 1981

In 1981, Satyatji Ray made Sadgati (1981), which means “salvation” or “deliverance” in Bangla. It is a brilliant film, in which Om Puri acts as Dukhia and Smita Patil as Jhuria, his wife. Mohan Agashe plays a brahmin and Gita Siddharth plays his wife.

What is interesting about the film is that Dukhia makes every possible arrangement to feed the brahmin, since he is supposed to visit his home in order to fix the date for his daughter’s wedding, but doesn’t. When the brahmin finally agrees to visit the house, Dukhia is asked to work for him for free. On an empty stomach, an unwell Dukhia is made to chop hard wood by the brahmin. At one point, while the brahmin has his lunch, he suggests to his wife that she give him some leftovers. Since the rotis were not enough, the brahmin suggests the wife makes some more food, but she refuses to take the trouble for it. Dukhia goes on chopping wood. Jhuria becomes anxious as she keeps waiting for him.

Also Read | The journey of an “Indian” woman through the Hindi cinema

At this point, another person from a lower caste stops by, to whom Dukhia says that he simply cannot chop more wood without a smoke. The person offers to get it for him and does, and Dukhia goes to the brahmin’s house to light it. As he tries to step inside, the wife throws the light at home, which hurts his feet. He immediately apologises for stepping into the house. The story takes an even more tragic turn when Dukhia finally dies chopping wood, and in protest, the person who offered him the smoke orders all others not to handle the body themselves. The brahmin is then forced to drag the body out, but since he refuses to touch it, he throws a rope around one of Dukhia’s legs and then drags it towards a pond, in which he dumps it.

Somnath Avghade in Fandry, 2013

The next film, Fandry (2013), is by Nagraj Manjule and in Marathi. The word “fandry” translates to “pig”, and one of the tasks that the protagonist Kachru (Somnath Awghade) or Jabya’s father is made to do by the region’s upper castes, is chasing pigs. A lower caste boy from the Kaikade community, Jabya falls in love with Shalu (Rajeshwari Kharat), from who belongs to an upper caste. Jabya and his friend believe that if they catch and burn a distinctive black sparrow and it’s ash is then applied on someone, it hypnotises the person to fall in love with the one who applies it. Sadly, these are only Jabya’s dreams, of which he has plenty. Another of Jabya’s dreams is to buy a pair of jeans. Jabya goes to the store, sees a pair of jeans, looks at the model’s face and comes back and takes a clothes pin and clamps his nose with it so he can look like the model. Towards the end of the film, we see Jabya exploding with rage, grabbing a rock and throwing it at his oppressors. However, he does not get to meet Shalu nor does the oppressive caste system around him disappear. The film is peppered with paintings of Ambedkar and in one instance, a teacher speaks of a dalit poet in a classroom.

Karnan (2021), a Tamil film made by Mari Selvaraj, is based on a real life incident. The village of the lower castes portrayed in the film has no bus stop of its own. No matter how many times the village elders have tried to get one built, their pleas have fallen on deaf ears. In fact, the upper caste village nearby and the police officers have joined hands in ensuring that this village suffers in silence. Interestingly, this is perhaps the only dalit issues-based film that suggests a revolution of sorts. In response to the system’s indifference to their demands, the villagers gather and unleash an attack on a bus, shattering all its window panes. The police arrive to settle the issue and the scene ends there.

Also Read | How cinema signals caste power

In another incident, Karnan (Dhanush), the protagonist, is then shown persuaded by those around him to apply for the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). He tries but doesn’t get in due to his caste. Karnan refuses to leave and returns to fight. The film makes use of multiple symbols, all of which are crucial to the story. The horse is the most interesting — it’s known widely that in many parts of India, dalits are not allowed to ride horses at their weddings and such. Yet, the only thing one of the young boys in the film wants to do is to ride a horse, and he makes sure he gets it.

Dhanush as Karnan in Karnan, 2021

One day, the police round up all the villagers and take them to the police station. They ask one of them (G. M. Kumar) what their name is and he replies “Duryodhanan”. He immediately gets beaten up and is asked how he, a dalit, can be “Duryodhanan”, a character in the Mahabharata. At another point, Karnan frees a donkey whose legs are tied. Yet another symbol of freedom for dalits, perhaps. We’re also shown another scene in which Karnan picks up a sword and rides back on a horse with it. He attacks all the cops who have been attacking them. The other cop who attacked Duryodhanan earlier is asked his name, to which he replies “Kannapiran” and that his father’s name is “Kandaiah”. Karnan then asks him, “why can’t Maadasamy’s son be named Karnan?” Another image that keeps appearing throughout the film is that of a young girl with a mask — the dead sister of Karnan. Early on in the film, she appears before her father to say that she has a treasure buried under their hut. Following this vision, they dig the floor and actually find a treasure there. Each time the villagers emerge victorious, she seems to appear and clap in joy. At the end of the film, Karnan is shown as married to his lover. The village is shown to have finally received a bus stop. The kids can finally go to school and the young girl, Karnan’s sister, claps in joy.

This is part two of a two-part series. Read the first part here.

Jeroo Mulla has taught film appreciation, photography, communication and supervised student documentaries for over 30 years. She was the Head of the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media (2012-2013) and the Head of the Social Communications Media Department, Sophia Polytechnic (1986-2012). Mulla has also served as a Jury for the National Film Awards (2010), a Selection Committee member for the International Children’s Film Festival Hyderabad (2011, 2013), and as an Advisory Panel Member at the Film Censor Board (1987). She is currently a visiting faculty at Sophia and various other media institutes. She is also on the Advisory Board of Women in Film and Television (WIFT) and of the Asia Society for their New Voices Fellowship for Screenwriters.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.