Underweight and Stunted Children: The Indian Paradox

Recent studies have shown that even as India fares better than many developing regions of the world on several indicators of growth and development such as GDP, per capita, Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), literacy, life expectancy, etc., the number of malnourished children in India is significantly high. What explains this paradox?

The Union Cabinet recently approved a multi-sectoral nutritional programme proposed by the Ministry of Women and Child Development to reduce under-nutrition in 200 districts across India. The 1,213 crore initiative will incorporate several schemes to curb malnutrition among children below the age of 3 years, and tackle anaemia in young girls and lactating mothers.

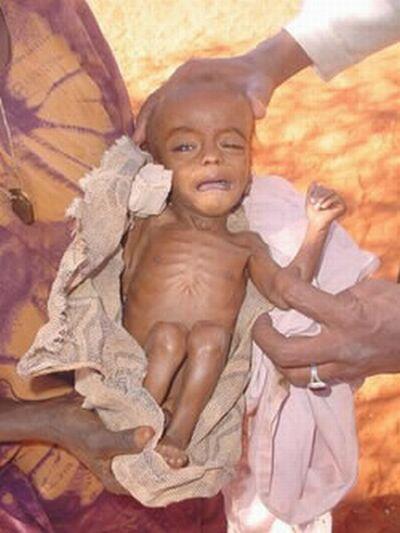

This nutrition initiative comes against the backdrop of several recent statistics and debates in the media on high levels of child malnutrition in India. In January 2012, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh released the “HUNGaMA Survey Report 2011”prepared by Naandi Foundation that covered 112 districts across India. According to the report, 42.5 per cent of children under five years of age are underweight (low weight for age); 58.8 per cent are stunted (low height for age), and 11.4 per cent are ‘wasted’ (low weight for height).

Image via: Shivaji Foundation/flickr.com

The alarming figures led Prime Minister Singh to call it a “national shame”. In the “Global Hunger Index 2013”, India scored 21.3 on the level of hunger, placing itself in the category of “alarming levels” of hunger. Apart from India, Haiti and Timor-Leste are the other two non-Sub-Saharan African countries that fall under this category. The report also highlights that South Asia is home to the largest number of hungry people in the world, followed by Sub-Saharan African countries.

According to the report, neighbouring countries of Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have scores less than 19.9, thus falling under the category of “serious” levels of hunger. Bangladesh that showed high rates of malnutrition until recent times has taken significant steps to improve nutrition, and quantity and quality of food intake. Progress has been made in cereal and non-cereal food production to ensure food security. Educational campaigns on exclusive breastfeeding and hygeine have helped the country to tackle malnutrition. In addition, Bangladesh is one of the 42 countries that are part of the “Scaling up Nutrition” (SUN) movement to implement nutrition specific approaches and interventions to curb malnutrition. India is not a part of the SUN movement.

Thus, what was previously dubbed by researches as the “Asian Enigma” to refer to the phenomenon of South Asian countries falling behind in standards of child growth despite economic growth, now seems to be modified into “Indian Enigma” or the “Indian Paradox” to reflect upon the phenomenon of India having a large number of under-weight and stunted children despite a growing economy.

Since income plays a huge role in the health standards of a country, the growth in GDP should reflect an expansion in people’s opportunities to better living conditions and improved nutritional levels. But even as India grows at a rate of 5-6 per cent in terms of GDP every year, rates of under-weight and stunted children in India have been significantly high. A report published by UNICEF in 2011, titled "The Situation of Children in India", stated that 43 per cent of children below five years of age were underweight, and 48 per cent were stunted.

The UN has estimated that about 2.1 million Indian children die before they reach the age of five years from preventable illnesses such as diarrhoea, malaria, typhoid, pneumonia and measles. According to a news story titled "Malnutrition Ravages India's Children" published in the India Ink blog of the New York Times, a 10-month-old severely malnourished Priya died of pneumonia in Bandrachiwadi village in the district of Thane in Maharashtra. The newsstory says that more than half of the 60 children, who died of diseases such as pneumonia in July 2012-July 2013 in the Jawhar subdistrict in Thane, were severely malnourished.

Statistics and reports on levels of malnutrition in India being higher than that in Sub-Saharan African countries have sparked criticism from many quarters. Among the critics is Economist Arvind Panagariya, a professor of Economics in Columbia University in the US. Panagariya has stated that genetic differences between Indians and Africans have not been taken into consideration while compiling the data on child growth. He has said that since Indian children are genetically shorter than African children, it is likely that the data will reflect that.

However, Dr. Uma Chandra Mouli Natchu, an assistant professor in pediatric biology at the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute (THSTI) in Gurgaon, said that being genetically short is not the problem. “Nobody dies of short height. But if stunted children in India have a high mortality rate, then there is a problem that needs to be addressed,” he said.

Professor Panagariya has also argued against the WHO-specified standards saying that if the standards have been derived from a population which is geneticallly taller and heavier than Indian children, then even a healthy Indian child will be considered malnourished. Dr. Natchu dismissed this argument stating that the WHO-specified standards, which were revised in 2006, are based on statistics of more than 8000 children from six countries around the world to create a fairly inclusive standard. These countries include the USA, Brazil, Oman, Ghana, Norway and India. “No one is complaining that Indian children are below the average (standard height-for-age and weight-for-age). The problem is that they are below the lowest value (minimum),” he said.

Stunted children are susceptible to infections due to a weak immune system. When they grow up to adulthood, they are likely to have a risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. Stunting also results in impaired cognitive ability, fatigue, loss of interest and curiousity, and failure to learn motor skills, which results in stunted children falling behind their healthier counterparts, and eventually dropping out of school.

Image via: http://www.humanrights.asia

Stunting affects a country’s growth and development since an undernourished adult is likely to have lower productivity and therefore earn lower income and contribute less to the economy. A report titled “A Profile of Youth in India” as part of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) of 2005-06 states that 44 per cent of women aged 15-24 and 30.7 per cent between 25-49 have BMI levels less than 18.5, thus abnormally thin. The data for men in the age group of 15-24 and 25-49 is 47.3 and 26.9, respectively.

Although there is no one single cause for child malnutrition in India, there are two arguments that have been widely discussed in recent times.

Child malnutrition is directly related to malnutrition among women, says a study titled “Child Malnutrition and Gender Discrimination in South Asia” by Santosh Mehrotra, who is a former Regional Economic Advisor for Poverty (Asia) for UNDP. Poor health of a woman during her infancy, childhood and teenage years leads to low birth-weight of her child. Consequently, children who are born with low birth-weight often experience poor health during their infancy and childhood.

The 2006 study published in the Economic and Political Weekly says that women most at risk nutritionally are those between 140 cms to 150 cms in height. Such (stunted) women are at high risk of having a difficult delivery due to a smaller pelvic size, and have higher chances of delivering a child with low birth-weight. 13 per cent of Indian women are below 145 cms. A BMI of less than 18.5 is an indicator of chronic energy deficiency. The study states that 36 per cent of Indian women fall short of that number.

The study further says that on average 52 per cent of Indian women suffer from mild, moderate or severe anaemia which is the underlying cause of maternal mortality and perinatal mortality. Anaemia is a deficiency of red blood cells in the body due to insufficient intake of iron-rich foods. Foods high in iron include dark, leafy greens, red meat, egg yolks, dried fruits such as raisins, and beans, soybeans, etc. Most foods in this category are unaffordable to women from economically weaker sections. Anaemic women are more likely to have premature delivery and deliver a child with low birth-weight than women who have sufficient iron intake.

“It is important to target women not only when they are pregnant, but otherwise as well,” said Dr. Amit Sengupta from Delhi Science Forum. “Women are discriminated right from birth, so by the time they reach adulthood, they are already malnourished,” he said.Santosh Mehrotra says in his study that in most poor households, women and young girls eat the leftovers after the males in the family have eaten their meals.

Insufficient intake of nutrients during childhood and adolescence because of gender discrimination within families is a leading cause for malnutrition in girls and young women. The study states that 17 per cent of scheduled caste women and 13.5 per cent of tribal and other backward caste women are below 145 cms in height. While the data for upper caste women is 11 per cent. Similarly, 41 per cent of rural women have a BMI of less than 18.5, and 20 per cent of scheduled caste and scheduled tribe women also fall under 18.5.

Another cause for stunting and under-weight children in India is aruged to be a consequence of a larger sanitation problem of open defecation. Dean Spears, a visiting researcher at the Delhi School of Economics, has argued that stunting as a phenomenon among Indian children could be linked to open defecation. Spears says that children are exposed to the germs in faeces when those germs are released in the enviornment during open defecation. This exposure to the germs causes children to suffer from diarrhoea and environmental enteropathy (causing chronic changes in the intestines of the children and preventing the body to absorb and use nutrients). Thus, leaving the children stunted.

In his study titled “Open Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India: An ecological analysis of new data from 112 districts”, Spears says that according to the 2011 Indian census, 53 per cent of Indian households did not use any kind of toilets. He further says that Bihar has had a higher rate of open defecation in the past ten years than any other country, and that Uttar Pradesh alone is home to 12 per cent of all the people worldwide who openly defecate.

He argues that the rate of open defecation in India has been higher than that of Congo, Ethiopia, Angola, Zambia, South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya, Ghana and many other Sub-Saharan African countries. He further states that only 38 per cent of Nigerians had openly defecated in the year 2008, and only 30 per cent of people in Zimbabwe in 2005 defecated in the open. Bangladesh, which had 44 per cent of its population defecating in the open in 2003, has now reduced it to 4 per cent due to government efforts in improving sanitation facilities and educating people about the consequences of open defecation.

Spears also argues that even the households that do not practice open defecation face the spillover effects of those who do.

Consequently, even though food security is instrumental for the health and nutritional needs of the children, diseased surroundings can still render a child malnourished.

Image via: Madhu Babu Pandi/flickr.com

“After the initial six months, the child eats food outside of mother’s milk. It is also the time when the child becomes active and acquires respiratory and gastrointestinal infections,” Dr. Amit Sengupta said. Thus, nutritional policies need to focus on the early years of the child.

One such programme is the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme (populary called ‘Anganwadi’) launched in 1975 to meet early childhood requirements by fighting malnutrition and reducing mortality. However, before 2005, ICDS focused majorily on children in the age group of 4-6 years to tackle malnutrition while malnutrition affects in the age group of 0-3 years. Also, ICDS still needs to go a long way in bridging the gap between planning and implementation by providing good infrastructure for the Anganwadi centres, speedy delivery of nutritional and health supplements, and adequate immunisation facilities.

Dr. Vandana Prasad from Public Health Resource Network said, “Many factors contribute to child malnutrition. Lack of food, lack of good quality and diverse food, lack of child care services, malnutrition among the mothers, open defecation... but it becomes problematic when one reason is highlighted as the primary reason.”

Although several factors are responsible for underweight and stunting in Indian children, poor health of mothers and open defecation are the most debated factors that affect child growth in India. It is, therefore, important to take immediate actions to improve women's healthcare and provide people sanitation faclities.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.