The Cold Calculus Behind Rise of Hindu Nationalism

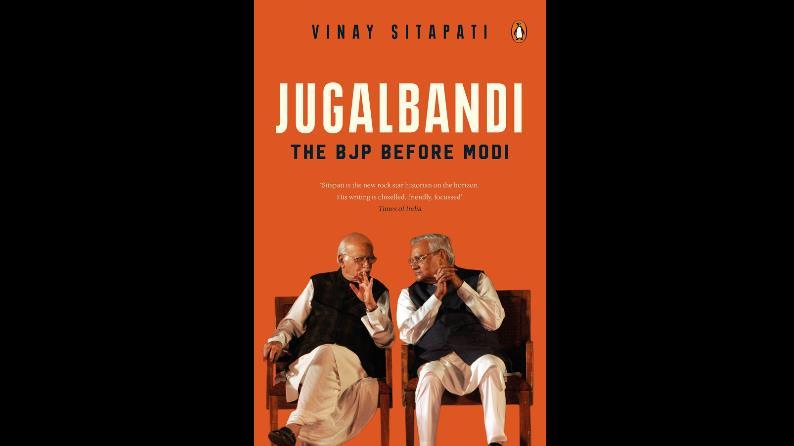

Vinay Sitapati’s Jugalbandi retells the history of Hindu nationalism through the intertwined lives of two of its chief protagonists, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani. The book goes further back to provide a rationale for the rise of Hindu nationalism, from the first general election based on universal adult franchise in 1920 and the formation of the Muslim League, but those details are sketchy.

“Jugalbandi” literally means “entwined twins”—commonly used to refer to musical duets. The author tries to give equal prominence to Advani, Vajpayee’s comrade-in-arms, but Advani ends up playing a supporting act to Vajpayee’s central character, as in real life. The book closely traces the fortunes of the Jana Sangh, and its child, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), through the fortunes of these lead characters and their chemistry. In piecing together Vajpayee’s political career, Sitapati does better than many biographers with his sheer ability to analyse and theorise based on extensive research.

The author uncovers the ruthless side of Vajpayee’s political persona—and how he specifically reserved it for his rivals within his party. Soon after the death of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya in 1967, Vajpayee wrests control of the party following a protracted power struggle with Balraj Madhok, a former party president and Vajpayee’s senior. The book details how Advani was very much Vajpayee’s protégé, from his days as secretary to the newly-elected Vajpayee in Parliament in 1957 to being propped up as president in 1973 by Vajpayee to stave off the likes of Madhok. Though only three years younger to Vajpayee, Advani’s career took off only after this out-of-turn elevation and the reader can draw parallels between the low-profile Amit Shah’s promotion to party president in 2014.

The author’s insights on how Vajpayee went out of his way to cut rivals to size from Madhok, ML Sondhi, Nanaji Deshmukh and Subramanian Swamy, in sharp contrast to his image as a consensus man and democrat who operated within the Nehruvian consensus, is among the highlights of this book. Sitapati is also unapologetic in foregrounding Vajpayee’s relationship with Kaul, a second cousin of Indira Gandhi’s, and acknowledging that it was not platonic. He argues that Kaul liberalised and socialised the provincial politician in Vajpayee and credits him for standing up to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in refusing to break off this relationship despite being explicitly ordered to. The author ends that portion with a quote of a Yadav politician from Bihar: “Vajpayee was let off because he was a Brahmin. Only Brahmins are allowed to break brahmanical rules.”

Sitapati also draws the importance of Advani’s role as his “other half” in politics. Apart from Advani’s deference to Vajpayee and his self-doubt, the author credits the durability of the partnership to their shared ideology and its emphasis on unity. A central theme running through the book is the “Hindu Fevicol” of unity as the “secret sauce” to the BJP’s success.

The book examines the about-turn in the Vajpayee-Advani hierarchy in 1986, when Vajpayee was side-lined in the party. A decade later, Vajpayee re-emerges as Advani’s boss through the latter’s benevolence but does not do justice to his “number two” in the Cabinet. Brajesh Mishra, the all-powerful principal secretary and national security adviser ran the show on Vajpayee’s behalf when he was prime minister. Yet, Vajpayee defers to Advani on party matters and lets him run organisational affairs. So, Advani was effectively the president of the party even as lightweights formally occupied the position during the BJP’s 1998-2004 government, just as Amit Shah is in control of the organisation today with JP Nadda as its ceremonial head.

The book explores how the Sindhi missionary school-educated Advani, from a particularly rich family in cosmopolitan Karachi was more of a “Macaulayputra” than the typical Gangetic Brahmin Vajpayee. The Partition which suddenly rendered Advani a refugee left an indelible wound in his heart and forever shaped his politics.

Vajpayee’s attempts in 1980 to emerge as Jayaprakash Narayan’s legatee with “Gandhian Socialism” did not work out despite getting a good number of leaders with secular image into the nascent BJP, including Jaswant Singh from the Swatantra Party, lawyer Ram Jethmalani and a prominent Mulsim face in Sikandar Bakht—all from non-RSS backgrounds. Even MC Chagla and Shanti Bhushan graced the first national convention of the BJP in 1980.

While Advani mostly deferred to Vajpayee even in the early to mid-1980s when the inchoate sense of Hindu victimhood was finding its feet in the aftermath of the Meenakshipuram mass conversions of 1981 in Tamil Nadu, Sikh separatism in Punjab and the refugee crisis in Assam, he had to take a call on aligning his party more with the RSS and riding the Hindutva wave that the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP, or World Hindu Council) was now championing.

Sitapati is on point when he explains how the RSS mothership floats rival organisations to the BJP to serve its interests whenever its political arm does not go according to its script. The revival of the VHP in 1983 under Gorakhpur Mahant Avedyanath (predecessor of Adityanath) and floating the Swadeshi Jagran Manch led by Dattopant Thengadi in 1991 are cases in point.

Originally, the VHP was founded in 1964 through the efforts of Golwalkar, SS Apte and Swami Chinmayanand to try and unify the various Hindu sects and codify Hinduism a la Hindu Vatican. However, this project was put on hold after a violent Parliament march demanding a ban on cow slaughter, when Deen Dayal Upadhyaya died in 1967. This template would later be replicated in the rath yatra undertaken by Advani in 1990, leaving behind a trail of dead bodies.

The author argues that Advani’s rath yatra was an opportunistic exercise, done purely for political considerations. Vajpayee is supposed to have asked Advani to call off the rath yatra after initial reports of violence. Advani, for once, turns Vajpayee down. The author acknowledges that Advani does not go the whole hog to capitalise on the sentiment despite setting the stage for it. The only other time Advani would overrule Vajpayee was on the latter’s insistence that Narendra Modi be sacked as Gujarat chief minister in 2001. As Advani had the ear of the party cadre, he is supposed to have taken a call to give more importance to the overwhelming sentiment prevailing in the party back then.

According to Sitapati, unlike Modi and Shah, who wear their communalism on their sleeve, Vajpayee and Advani had to operate through dog whistles. Advani lacked the forked tongue of Vajpayee. The author explains that the moderate turn of the Jana Sangh in 1973 followed the pragmatic Balasaheb Deoras taking charge as its chief from Golwalkar, who had led the body for 33 years. This was when Vajpayee’s control over the party became absolute and he got the relatively junior Advani elected as president and then got him to suspend Balraj Madhok for three years, which became his permanent banishment.

Sitapati attempts to bust the urban legend that Vajpayee likened Indira Gandhi to Goddess Durga after the 1971 war, but he perpetrates the other myth involving Vajpayee and Nehru where Nehru is supposed to have told the visiting Soviet Union premier Nikita Krushchev that one day the young Vajpayee would become prime minister—there is no evidence to prove this apocryphal story.

There are interesting tidbits on how Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s grandson Nusli Wadia was, ironically, the major financier of the Jana Sangh and the BJP and how the canny businessman extracted his pound of flesh when Vajpayee was Prime Minister. Vajpayee’s technique of ousting leaders whom he perceived as a threat is also a running theme and the instance of scuttling Nanaji Deshmukh’s cabinet berth offered by Morarji Desai stands out. An indignant Deshmukh, the general secretary of the Janata Front in the Emergency years, got himself exiled to Chitrakoot to retire from public life.

There is another interesting bit about Vajpayee’s evening durbars during the late eighties (his low phase) where an impeccably-dressed Brajesh Mishra and Jaswant Singh were always in attendance, along with Virendra Kapoor and Ashok Saikia. Apart from his drink, Vajpayee was fond of bhang (opium-laced) pakodas and prawns whose steady supply was ensured by Kaul, as recalled by his future private secretary, Shakti Sinha. When Vajpayee eventually became prime minister, this cabal would become the centre of power in Lutyens’ Delhi.

Where Sitapati falters is in glossing over the RSS’ role in the whole Hindu nationalist movement by portraying it as a less than potent entity. Then again, so much of what he digs up may not have been possible for a researcher antagonistic to the Sangh and Sitapati’s brilliance in theorising with the available facts gives a new dimension to written history.

Sitapati’s heavy reliance on anecdotes, many of them traced back to a single anonymous source, to make crucial assumptions that hold the narrative together, is a major drawback. The most incredulous story is that of a 33-year-old first-time Gujarat MLA, Amit Shah, writing an “angry letter” to Vajpayee on the tactical blunder of testing nuclear weapons in 1998 “and losing Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) forever in the process”. This is supposed to have been revealed confidentially to a journalist by Shah. Another such “revelation” traced back to this journalist, who wishes to remain anonymous, is of a twenty-one-year-old Shah overhearing a chance conversation between Vijayaraje Scindia and Vajpayee while standing guard outside their room during the Gandhinagar National Executive of the BJP in 1986. A messenger comes with a missive from RSS chief Balasaheb Deoras asking Vajpayee to resign in favour of the Rajmata. Now, this bit is crucial to the whole narrative and Sitapati’s own inferences but all he has to rely on is an anonymous journalist to whom Shah is supposed to have passed this information. Sitapati has clearly not applied the lessons he learned in his time as a journalist. The author’s over-eagerness to bring Narendra Modi and Amit Shah into the narrative at every turn in the latter part of the book, often to juxtapose their version of Hindu nationalism with the Vajpayee-Advani duo’s, could be the reason for these slip-ups.

Sitapati has managed to access a good number of RSS sources including the 97-year-old MG Vaidya, yet he has not managed to speak to Advani, for instance, and relies heavily on the latter’s 2010 autobiography, My Country, My Life, to piece together his inferences. Similarly, Sitapati has relied on Jaswant Singh’s writings and pretty much everything available on Vajpayee to draw his theories. The information gleaned from the private papers of ML Sondhi and a lot of first-person interviews with people ranging from Subramanian Swamy and Yashwant Sinha to NM Ghatate and Virendra Kapoor over a four-year span, is a testament to the meticulousness of Sitapati.

The author ends by raising three questions for scholarly debates, but I would add a fourth on whether Sitapati treats the RSS with kid gloves. As with movies, what readers draw from a book would greatly depend on the individual and, having grown up on a staple of AG Noorani’s writings on the Sangh, Sitapati’s treatment of the RSS does come across as slightly less than objective, especially since he pulls no punches while making sharp observations of his protagonists, Vajpayee and Advani.

Last but not the least, the flair and flourish in Sitapati’s language is what makes the book eminently readable. His prose is as lucid as Ramchandra Guha’s although when it comes to ideology, the former would be “Centre-Right” than the unapologetically liberal Guha.

The author is an independent journalist and former editor of The Kochi Post. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.