White Saviorism, Victimization and Violence

On October 31, 2014, Blaise Campaoré, the despotic ruler of Burkina Faso, was overthrown by mass uprisings almost exactly 27 years after he had seized power through the assassination, on October 15, 1987, of Thomas Sankara – popularly referred to as the “Che Guevara of Africa”.

Burkina Faso provides an excellent case study for understanding the conditions under which the white savior industry thrives or dies.

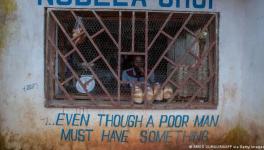

The République de Haute-Volta (Upper Volta) as it was once known, and which was once part of the French Union, obtained independence from France in 1960. This tiny impoverished country was grossly underdeveloped, with an illiteracy rate of 90%, the world’s highest infant mortality rate (280 deaths for every 1,000 births), inadequate basic social services, one doctor per 50,000 people, and an average yearly income of $150 per person, and unable to feed its population. Highly indebted, its people had been rendered into the perfect image that nourishes the white savior complex , as Walter Rodney described, “A black child with a transparent rib-case, huge head, bloated stomach, protruding eyes and twigs as arms and legs was the favourite poster of the large British charitable operation known as Oxfam.”1

Following a series of coups and counter-coups that eventually led Thomas Sankara and his comrades to power in 1983, an extraordinary revolution was launched in the country. In the space of just four years, the country became self-sufficient in food, its infant mortality rate halved, school attendance doubled, 10 million trees planted to halt desertification, and wheat production was doubled. Land and mineral resources were nationalized, railways and infrastructure constructed, and 2.5 million children immunized against meningitis, yellow fever and measles. Nearly 350 medical dispensaries and schools were constructed across the country by communities. FGM, forced marriages and polygamy were outlawed, and women were actively involved in decision making at all levels. In order to achieve this Sankara did not ask for aid – on the contrary, he shunned it. Moreover, he argued that the debt owed by the country was odious and therefore should not be paid. Cotton production therefore was not directed to export but was used to support a thriving Burkinabé textile industry. The country was marked in particular by the almost complete absence of foreign aid agencies and their local counterparts, the development NGOs.

Image Courtesy: pixabay.com

Sankara’s assassination at the hands of Blaise Campaoré, supported and celebrated by France and the rest of the imperial world, was to bring about a reversal of all the gains of that short period. Under Campaoré, the country quickly returned to the conditions of the former République de Haute-Volta. Cotton was once again grown for export comprising 30% of its GDP of $1500, making it one of the lowest in the world. Today, Burkina Faso is classified as one of the highly indebted poor countries (HIPC), with more than 80% of its population living on less than $2 a day, and nearly 50% on less than $1 a day. Infant mortality rates have been increasing. Literacy levels have fallen back to around 12%, with less than 10% of primary scholars reaching secondary school. In contrast to the program of ‘land to the peasant’ initiated under Sankara, Campaoré’s policies were more like land to the parliamentarians and the president’s family! Corruption is deep, with millions allegedly being syphoned off from aid and from handouts from mining companies. A large part of the economy is in fact funded by international aid. Privatization of water and other utilities has been the order of the day. A number of transnational mining corporations have been allowed to excavate gold and other minerals, with almost no benefit to the population at large. And the regime was not averse to using violence and assassinations to deal with its opponents.

These were the conditions needed for the flowering of agents of the white savior industry. In contrast to Sankara’s time, Campaoré’s rule was characterized by the growth in the involvement of the transnational development NGOs and an exponential growth in the number of their local Burkinabé counterparts. Oxfam Québec’s involvement in Burkina Faso, for example, escalated after Campaoré took power in 1987. The number of Burkinabé NGOs are thought to be in the hundreds, each depending on foreign aid, each ready to present Africans as victims, in need of rescue, not least from themselves, as the basis for getting grants. They flourished under a regime that had retrenched from its responsibilities for providing social services, and which has systematically dispossessed its people by privatizing the commons. The regime actively encouraged this growth of NGOs supported by international aid as the basis for absolving itself of any responsibility for improving the lives of the majority.

For saviors to exist, there must be those in need of ‘saving’. Put another way, saviors require victims. Victimization — that is, the process of making other humans victims — is necessarily a fundamental requirement for there to be a savior complex. And by definition, white savior complex is premised on the victimization of the African, the black body. Thus, it has become conventional in the West to describe Africans only in terms of what they are not.

They are considered chaotic not ordered, traditional not modern, tribal not democratic, corrupt not honest, underdeveloped not developed, irrational not rational, lacking in all of those things the West presumes itself to be. White Westerners are still today represented as the bearers of ‘civilization’, the brokers and arbiters of development, while black, post-colonial ‘others’ are still seen as uncivilised and unenlightened, destined to be development’s exclusive objects.2

But to fulfill this image of Africa requires the complicity of the African state and African NGOs, each to carry out its own form of violence. First, as the case of Burkina Faso illustrates, it requires the violence associated with destroying the emergence of self-worth, self-determination and dignity that was the achievement of the short-lived revolution led by Sankara. That violence is also necessary if the new rulers are to use the state as a source of private accumulation by dispossession for the benefit of a few.

The local NGOs, whose survival is dependent of receiving handouts from the white savior industry, are complicit in nurturing the image of the subservient, incapable, primitive, African, the victim that needs saving. The complicity of African NGOs, and indeed of African leaders, in perpetuating a form of self-hate of the African identity, a modern manifestation of Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks, is a painful and too often unacknowledged form of violence.3

Saviors cannot thrive where a people retake control of their destinies, assert their dignity and humanity, create the structures for self determination, organise to produce and make collective decisions, take pride in their own cultures, and seek neither aid, grants or charity. Indeed, the very name of the country, Burkina Faso, “the land of upright people”, that Sankara introduced in 1984, is anathema to the white saviour industry.

What Burkina Faso experienced over a period of nearly thirty years has all the hallmarks of the set of neoliberal economic policies imposed with varying degrees of violence across the continent. The result of these policies has been not only global economic and financial crises, but also crises of credibility of today’s rulers, as demonstrated in the rise of a profound discontent amongst the people. That Camporé was deposed through mass mobilizations against his attempt to prolong his rule (and that of his family) should not have come as a surprise; the set of conditions that has so enraged the Burkinabé are similar to those that led to the mass mobilizations and removal of Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt. These are only the first of many uprisings to come in Africa. And in none of the uprisings to date, and I would venture, in none of those that are to come, will we witness banners proclaiming ‘we want more aid’ nor ‘we want to be rescued by white saviors’.

What these uprisings, whether in Africa or beyond, require is neither rescue nor aid, but rather solidarity. Speaking to popular movements recently, Pope Francis described the act of solidarity thus:

It is to confront the destructive effects of the empire of money: forced displacements, painful emigrations, the traffic of persons, drugs, war, violence and all those realities that many of you suffer and that we are all called to transform. Solidarity, understood in its deepest sense, is a way of making history, and this is what the Popular Movements do.4

And in that, everyone everywhere can participate.

Firoze Manji works for ThoughtWorks (www.thoughtworks.com) and heads the Pan-African Baraza (www.thoughtworks.com/insights/pan-African-institute). He is the founder and former editor-in-chief of Pambazuka News (www.pambazuka.org)

1 Walter Rodney (1973): How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Oxford: Pambazuka Press, 2011

2 Manji F, O’Coill C (2002) The missionary position: NGOs and development in Africa. International Affairs 78 (3), 567–583.

3 Frantz Fanon: Black Skins, White Masks. New York, Grove Press (revised edition 2008)

4 Pope Francis speaking to a gathering of social movements at the Vatican, October 27- 29, 2014, http://www.devp.org/en/articles/pope-inspires-popular-movements-continu…

A shorter version of this article appeared in the January 2015 edition of New African

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.