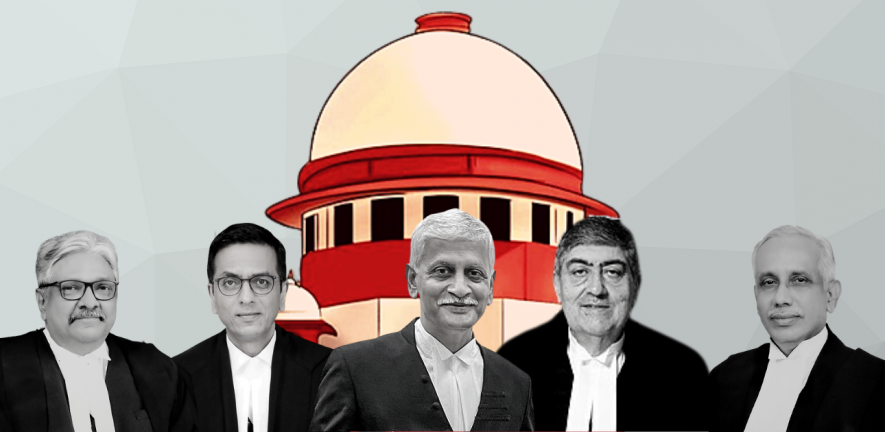

As the CJI U.U. Lalit-led Supreme Court Collegium Goes into a Limbo, He Upheld the Law by Seeking Written Opinion From its Members

With only one month to go before his retirement, the Chief Justice of India, U.U. Lalit-led Supreme Court Collegium stands crippled by a convention that the outgoing CJI-led Collegium does not meet to recommend judges during his last one month in office. But the two dissenting Judges within the Collegium are not legally right in questioning the CJI’s insistence on expressing their views on the recommendees in writing, though it can be said that a split decision from the Collegium favours the Executive.

—

On October 7, the Union Law Minister had written a letter to the Chief Justice of India (‘CJI’) Uday Umesh Lalit, seeking his recommendation on his successor as he is slated to retire on November 8, thus setting in motion the process of appointment of the 50th CJI.

The Law Minister’s letter is part of a process indicated in the Memorandum of procedure of appointment of Supreme Court Judges (‘MoP’). The MoP states as follows:

“Appointment to the office of the Chief Justice of India should be of the seniormost Judge of the Supreme Court considered fit to hold the office. The Union Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs would, at the appropriate time, seek the recommendation of the outgoing Chief Justice of India for the appointment of the next Chief Justice of India.

- Whenever there is any doubt about the fitness of the seniormost Judge to hold the office of the Chief Justice of India, consultation with other Judges as envisaged in Article 124 (2) of the Constitution would be made for appointment of the next Chief Justice of India.

- After receipt of the recommendation of the Chief Justice of India, the Union Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs will put up the recommendation to the Prime Minister who will advise the President in the matter of appointment.”

The MoP is a written document mutually agreed to by the Supreme Court Collegium of judges and the Executive, which lays down the procedure to be followed in making recommendations for the appointment of the CJI and the judges to the Supreme Court. A similar MoP is in place with regard to the appointments of the high court judges, and their transfers.

The MoP broadly incorporates what was held by the Supreme Court in the Second and Third Judges’ cases in 1993 and 1998 respectively. In the Fourth Judges’ case (the National Judicial Appointments Commission (‘NJAC’) case) in 2015, the Supreme Court’s Constitution Bench directed the Union Government to evolve a fresh MoP, to incorporate its proposals to reform the Collegium’s functioning. In its order on December 16, 2015, the bench dealt with eligibility criteria, transparency, secretariat, mechanism to deal with the complaints against recommendees, and interaction by the Collegium with the recommendees.

But with the government and the successive Collegiums not agreeing to the draft of the revised MoP, the old MoP – with which the Supreme Court’s Constitution Bench was dissatisfied – continues to govern the process of appointment to the higher judiciary.

It appears that the two judges who oppose the circulation method of consultation among the Collegium members are hesitant to put their views on the merits or otherwise of the proposed recommendees in writing, lest it becomes part of the record. An oral exchange of views at a closed-door meeting gives them the shield of anonymity, away from the public glare or the possibility of the court lifting the veil on their written comments at some point in the future.

In the NJAC case, the Constitution bench, while proposing to reform the working of the Collegium, did not contemplate any changes to the process of appointment of the CJI. Therefore, the Law Minister’s letter to the CJI to recommend the name of his successor, on the face of it, had nothing to do with the reform of the Collegium, envisaged by the Constitution bench in 2015.

However, this innocuous letter from the Law Minister to the CJI, comes amidst reports of serious differences within the Collegium on its procedure to be adopted in making recommendations. Two of the five members of the Collegium, according to reports, have expressed reservations about the CJI’s request to put their comments on the proposed recommendees in writing, to be circulated among the members, in the absence of a physical meeting to discuss their merits. What lends credibility to these reports is the fact that the Supreme Court has not officially denied them.

Thus, media reports suggested that among the four senior-most judges after CJI Lalit, two had extended their support to the circulation method proposed by him, while the remaining two strongly opposed it, saying such a thing was unheard of. It is not clear who among the four – Justices Dr. D.Y.Chandrachud, Sanjay Kishan Kaul, Abdul Nazeer and K.M. Joseph – chose to support or oppose CJI Lalit’s proposal for recording their views in writing on the proposed recommendees.

It appears that the two judges who oppose the circulation method of consultation among the Collegium members are hesitant to put their views on the merits or otherwise of the proposed recommendees in writing, lest it becomes part of the record. An oral exchange of views at a closed-door meeting gives them the shield of anonymity, away from the public glare or the possibility of the court lifting the veil on their written comments at some point in the future. It is also not clear whether the two dissenting judges are against the four names proposed by the CJI, but are only against the process of circulation, as suggested by him.

The names recommended by CJI Lalit to the four other members of the Collegium are Punjab and Haryana High Court Chief Justice Ravi Shankar Jha, Patna High Court Chief Justice Sanjay Karol, Manipur High Court Chief justice P.V. Sanjay Kumar, and senior advocate K.V. Vishwanathan.

While dealing with cases of non-appointment of recommended judges, the bench in the Second Judges case had held that in order to ensure effective consultation between all the constitutional functionaries involved in the process, the reasons for disagreement, if any, must be disclosed to all others, to enable reconsideration on that basis. All consultations with everyone involved, including all the judges consulted, must be in writing and the CJ of the high court, in the case of appointment to a high court, and the CJI, in all cases, must transmit with their opinion the opinion of all judges consulted by them, as a part of the record.

Reports indicate that there was a Collegium meeting scheduled on September 30, but it could not take place because the bench presided by Justice Dr. Chandrachud rose at 9 p.m. from the court that day as he wanted to complete the hearing of cases as shown in the cause list for the day. It is only because the scheduled meeting could not fructify that CJI Lalit proposed to the other members of the Collegium that they could use the circulation method to express their opinions on the recommendees proposed by him for appointment as the Supreme Court judges.

Are the dissenting Judges right in opposing circulation of views by writing?

It may be recalled that Justice Jasti Chelameswar, when he was a member of the Collegium headed by then CJI T.S. Thakur, would insist on circulation as he was boycotting the Collegium meetings, demanding transparency and objectivity in the appointment process. Thus, to say that the CJI’s letter seeking written consent is unprecedented, perhaps may not be correct.

That apart, there is sufficient merit in CJI Lalit’s plea for a written opinion, as articulated in the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Third Judges case. Although the Supreme Court’s nine-judge Constitution bench in the Third Judges case had given an advisory opinion in the context of recommending appointment of high court judges by the Supreme Court’s Collegium, there is no reason why it cannot apply to the recommendations for appointment of Supreme Court judges.

In the Third Judges case, the Union Government had requested the Supreme Court under Article 143 of the Constitution, to clarify certain questions of law, arising from the interpretation of the judgment in the Second Judges case. The seventh question therein was precisely framed thus: “Whether the government is not entitled to require that the opinions of the other consulted Judges be in writing in accordance with the aforesaid Supreme Court judgment and that the same be transmitted to the Government of India by the CJI along with his views”.

In the Second Judges case, another nine-judge Constitution bench had held earlier that the ascertainment of the opinion of the other judges by the CJI and the Chief Justice (‘CJ’) of the high court, and the expression of their opinion, must be in writing to avoid any ambiguity. While dealing with cases of non-appointment of recommended judges, the bench in the Second Judges case had held that in order to ensure effective consultation between all the constitutional functionaries involved in the process, the reasons for disagreement, if any, must be disclosed to all others, to enable reconsideration on that basis. All consultations with everyone involved, including all the judges consulted, must be in writing and the CJ of the high court, in the case of appointment to a high court, and the CJI, in all cases, must transmit with their opinion the opinion of all judges consulted by them, as a part of the record, it had been held in the Second Judges case.

“Expression of opinion in writing is an inbuilt check on exercise of the power, and ensures due circumspection. Exclusion of justiciability, as indicated hereafter, in this sphere should prevent any inhibition against the expression of a free and frank opinion. The final opinion of the Chief Justice of India, given after such effective consultation between the constitutional functionaries, has primacy in the matter indicated”, the judgment had stated in the Second Judges case.

CJI Lalit, considering the soundness of the principle laid down in the Third Judges case in the context of appointment of judges to the high courts, was correct in adopting the similar principle in the case of dissenting Judges within the Collegium, while appointing Supreme Court judges.

In the Third Judges case, the bench referred to the summary of conclusions in the majority judgment in the Second Judges case. It drew attention to point No. 22 of the summary, which reads thus: “Necessarily, the opinion of all members of the Collegium in respect of each recommendation should be in writing. The ascertainment of the views of the senior most Supreme Court judges who hail from the High Courts from where the persons to be recommended come must also be in writing. These must be conveyed by the CJI to the Government of India along with the recommendation. The other views that the CJI or the other members of the Collegium may elicit, particularly if they are from non-Judges, need not be in writing, but it seems to us advisable that he who elicits the opinion should make a memorandum thereof, and the substance thereof, in general terms, should be conveyed to the Government of India”.

Interestingly, the above view, though expressed in the context of the appointment of high court judges, has been adopted in the MoP in the context of the appointment of Supreme Court judges, and this has held the field all these years without any murmur from the Supreme Court Collegium.

The bench in Third Judges case agreed with this view and held that the objective being to gain reliable information about the proposed appointee, the CJI should, therefore, form their opinion in regard to a person to be recommended for appointment to a high court in the same manner as they form fit in regard to a recommendation for appointment to the Supreme Court, that is to say, in consultation with their senior most puisne judges. The bench was clear that such a Supreme Court judge who may be in a position to give reliable information about the proposed appointee, should be asked to do so, and all such views should be expressed in writing and conveyed to the government along with the recommendation.

While answering the specific question posed by the Government, the bench in the Third Judges case reiterated its view thus: “The views of the Judges consulted should be in writing and should be conveyed to the Government of India by the CJI along with his views to the extent set out in the body of this opinion”.

The Supreme Court may not have insisted in the Third Judges case that the expression of opinions within the Collegium ought to be in writing in the case of recommendations to appoint Judges to the Supreme Court. But it is certainly reasonable to suggest that CJI Lalit, considering the soundness of the principle laid down in the Third Judges case in the context of appointment of judges to the high courts, was correct in adopting a similar principle in the case of dissenting Judges within the Collegium, while appointing Supreme Court judges.

Scope of dissent within Collegium

As per the Second judge case, it is the CJI who proposes the name in the Collegium for the appointment to the Supreme Court. In fact, this has been a general practice prevailing, by convention, followed over the years, and continues to be the general rule.

The majority judgment in the Second Judges case said “if the final opinion of the Chief Justice of India is contrary to the opinion of the senior Judges consulted by the Chief Justice of India and the senior Judges are of the view that the recommendee is unsuitable for stated reasons, which are accepted by the President, then the non-appointment of the candidate recommended by the Chief Justice of India would be permissible”.

The judgment in the Third Judge case observes that “This is delicately put, having regard to the high status of the President, and implies that if the majority of the Collegium is against the appointment of a particular person, that person shall not be appointed, and we think that this is what must invariably happen. We hasten to add that we cannot easily visualise a contingency of this nature; we have little doubt that if even two of the Judges forming the Collegium express strong views for good reasons that are adverse to the appointment of a particular person, the Chief Justice of India would not press for such appointment.”

Explaining the Second Judge case, Justice Madan B. Lokur, in his concurring opinion in the NJAC judgment, said that the primacy of the opinion of the CJI is not to their individual opinion but to the collective opinion of the CJI and their senior colleagues or those who are associated with the function of appointment of judges, and therefore, the President may not accept the recommendation of a person for appointment as a judge, if the recommendation of the CJI is not supported by the unanimous opinion of the other senior judges.

Adding further, Justice Lokur said, “The President may return for reconsideration a unanimous recommendation for good reasons. However, in the latter event, if the Chief Justice of India and the other judges consulted by him/her, unanimously reiterate the recommendation ‘with reasons for not withdrawing the recommendation, then that appointment as a matter of healthy convention ought to be made.’” He emphasised that the key word here is unanimous – both at the stage of the initial recommendation and at the stage of reiteration.

Justice Lokur further held that the President is entitled to turn down a 4-1 or 3-2 recommendation. If a unanimous recommendation does not find favour with the President for strong and cogent reasons, and is returned to the Collegium for reconsideration, but it is unanimously reiterated, then the President is obliged to accept the recommendation. However, if the reiteration is not unanimous, then the President is entitled to turn down the recommendation.

To put it simply, if the Collegium’s recommendation is not unanimous, the President can turn it down. And if it is unanimous, and the President has some reservations against the name(s), they can seek reconsideration of the recommendation. Upon the reconsideration, if the Collegium unanimously reiterates the recommendation, then the President is obliged to approve the recommendation.

Should the Collegium take decisions by consensus?

It is reasonable and desirable to expect the Collegium to take decisions based on consensus. Perhaps, that has also been a long-standing convention. Should this practice be broken when the incumbent CJI has less than a month in the office? The answer should be negative. Taking decisions by majority will set an unhealthy precedent. It may also give an upper hand to the Executive, for the President is not bound to accept a recommendation of the Collegium which is not unanimous.

The judges to be appointed will function during the term of the incumbent CJI’s successor, and it is right that the likely successor should have a hand in their selection. Though it does not negate the majority rule, it does indeed recognise the pivotal position of the senior-most judge who also happens to be the successor of the CJI.

Also, let’s take a hypothetical situation. If one of the two dissenting judges is the successor of CJI Lalit, the incumbent should show deference to his views. Ordinarily, one of the four senior-most judges would succeed the CJI, but if the situation should be such that the successor Chief Justice is not one of the four senior-most puisne judges, they must invariably be made part of the Collegium. This is what was said in the Third Judges case.

The rationale is that the judges to be appointed will function during the term of the incumbent CJI’s successor, and it is right that the likely successor should have a hand in their selection. Though it does not negate the majority rule, it does indeed recognise the pivotal position of the senior-most judge who also happens to be the successor of the CJI.

Paras Nath Singh is a Delhi-based lawyer, V.Venkatesan is Editor, The Leaflet.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.