Cat is out of the bag: Ban on Holocaust Novel Maus Exposes Hypocrisy

The removal of the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel ‘Maus’ from an eighth-grade curriculum in Tennessee, USA, on grounds of nudity and profanity has drawn backlash from several Indian artists and academics who have said that there is no upside to shielding children from realities they are already exposed to.

It was 1984. Orijit Sen felt both vindicated and excited. As the college student looked at the cover of TIME magazine in the library of the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, he realised that it would finally stop his teachers from accusing him of wasting his artistic potential on drawing comic books.

A graphic novel that had just been released was making waves in the art world. It was not just any graphic novel—it was a work of art by an up-and-coming artist called Art Spiegelman. And the subject matter wasn’t kids’ stuff: it was the Holocaust. It was serious and political. The novel dealt with adult themes and was written for kids through anthropomorphic characters like rats, cats and pigs. It was subversive in every imaginable way and the author was featured on the cover of one of America’s most famous magazines.

“I showed Maus to my teachers that day and said, ‘Look, this is why I’m interested in comics,’” says Sen. “Spiegelman was one of those people who made me think that I was on the right track.”

Sen, who would go on to pen A River of Stories, India’s first graphic novel in 1994, on the social movement led by Adivasis against the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam, Gujarat, is not the only one to be inspired by Spiegelman’s postmodern memoir of his Polish father’s experiences as a Holocaust survivor.

A genre-amorphous work which sizzles with history and biography and fiction across panels and pages, Maus is the only graphic novel to have won the Pulitzer Prize. It is a classic of the underground comix movement in the 1980s.

Today, it has been struck from the eighth-grade curriculum of a school in Tennessee, USA, on allegations of nudity and profanity.

Orijit Sen. (Image credit: kindlemag.in)

The minutes of the meeting are in the public domain. The teachers of the McMinn County School Board cited eight swear words and a nude illustration as their justification for the ban. What followed was typical of the Internet apropos any attempts at censorship—the book shot to the top of Amazon’s bestseller list.

In the meeting, one of the Board members agreed that the Holocaust was “horrible, brutal and cruel” but didn’t like its portrayal in the book. He said: “It shows people hanging; it shows them killing kids. Why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff? It is not wise or healthy.”

Another teacher said: “We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history. We can teach them history and we can teach them graphic history. We can tell them exactly what happened but we don’t need all the nakedness and all the other stuff.”

But there are those within the comic art and literary community of India who are suspicious of these motives and believe that children can tolerate far more than nudity and profanity in an educational setting and context since they are exposed to worse outside the classroom.

Why was Maus really banned

“The nudity reference is a very obscure section of the comic, is not in an objectional way and isn’t even sexual,” says Sen. “It’s a very tragic situation of [Spiegelman’s] mother committing suicide. This sounds like a trumped-up reason. Maybe, there is some antisemitism involved.”

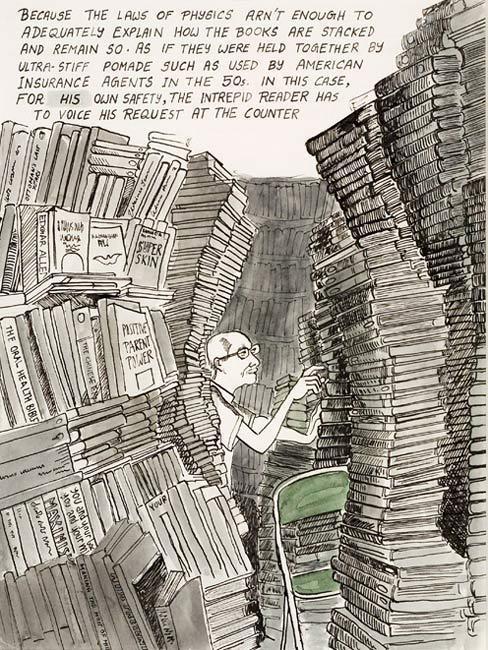

Sarnath Banerjee, a Delhi-based graphic novelist and co-founder of the comics publishing house Phantomville, feels similarly. “The worst-case scenario is that [they have banned the book] out of puritanical morality. The best case is that the teachers simply want to introduce these themes at a later age.”

Sarnath Banerjee, from Tyranny of Cataloguing, 2008. (Image credit: Saffron Art)

“They say they have banned it because of racist intentions and nudity. But I stand by as an artist and feel that we need to tell our children such realities,” says Uttam Ghosh, award-winning illustrator and political cartoonist at Rediff.com. “They have taken such a conservative stand. The book has been around for so many years. We are going backwards.”

Can comics help teach children about sensitive realities

Maus is a very important book about an evil chapter in history, and telling that story through a comic book was an easy way to reach kids and adults equally, according to Sajith Kumar, chief cartoonist, Deccan Herald.

“To ban it for nudity and profanity shows how short-sighted people are even in a first-world country,” Kumar says adding, “Knowing our history is to make amends to our everyday present and make this world a better place to inhabit by not repeating our past mistakes.”

Ananya Saha, assistant professor, department of English, St Xavier’s University, Kolkata, says, “Comics are a unique medium that can appeal to an audience across demographics—take Japanese manga for instance. In Japan, manga has been used for advertisement, promotion, marketing, social awareness and so on. In India, Amul has used the little girl figure for generations. The visual nature of the medium makes any issue more palatable and approachable.”

An Amul topical advertisement. (Image credit: Amul)

“A lot of very difficult conversations become way easier through personal narratives and also through the visual medium, which is not text-heavy. We live in a world where children are already exposed to far more profanity and nudity online [than the comic’s content],” says Indu Lalitha Harikumar, creator of Induviduality, an Instagram page of comic strips raising awareness around sex, gender and sexuality. “The more you censor something, the more it comes back. Which is what happened here. Maus was back in the news and more people read it.”

Literature has often been censored in the classroom but the thought that banning a book will protect children itself assumes the idea of childhood as being very distant from the dirty messy nature of our everyday life and that creates an artificial category, according to Chetan Anand, a teacher-educator from Shyama Prasad Mukherjee College, Delhi University.

“A child is then supposed to converge with the socio-political ends and ideological apparatus of the state rather than become a child whose ability to think for himself is affirmed,” Anand adds. “Certainly, the way not to expose children to sensitive realities would be by giving these dicta… rather exploring these questions through a child’s imagination.

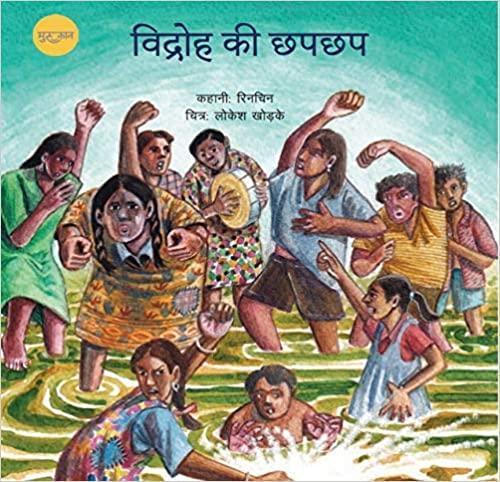

The idea of an idealised childhood is imprinted on our memories, according to Banerjee, but times have changed and childhood is going to become shorter with exposure to social media. This sentiment is echoed by Lokesh Khodke, a visual artist and co-founder of Bluejackal, a comics platform, who says that childhood is considered innocent and art created for children is often “opaque and protected” so that they aren’t affected by any realities—but children are already exposed to harsh realities.

Lokesh Khodke. (Image credit: The Guild)

“What our books do is take them away from that exposure,” Khodke says. “In actual life, they are aware of the social/political background they’re coming from… in terms of financial status, caste, parenthood and eating habits. But we produce stories and curricula in such a clean manner that all differences are eliminated. We produce stories for only a certain class and caste.”

How can we make our comics more inclusive

One of the projects that Khodke has recently illustrated is Vidroh Ki Chhap, a book released by Muskaan, a Bhopal-based NGO. The project worked closely with tribal children in urban spaces who are often harassed by the police and don’t attend school. Khodke took several references before beginning his sketches—he was determined that his characters had to look as close to such people in actuality. Most Indian comics, he says, are very urban-looking and that reflects in their characters who also dress and look like urban residents.

Vidroh ki Chhap. (Image credit: Amazon.com)

Khodke also illustrated the poem Mother, by Dalit and OBC ideologue Kancha Illaiah, in a book of short stories Different Tales: Stories from Marginal Cultures and Regional Languages, published by Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies, Hyderabad.

Sen, who has worked with Khodke, is the chief editor of Comixense, a quarterly comic published by Ektara Trust aimed at the young adult audience. It introduces mature themes into the series by tackling ideas like surveillance, technology, beauty notions and religion in the psychedelically illustrated issues that Sen has called “a dream come true” and an attempt to spark “intelligence, imagination and empathy” in children. He wanted to deflect opinions that comics couldn’t be serious.

“I put such stories in these comics precisely because we don’t have any discussions in classrooms about issues like these, which affect everybody,” says Sen. “Kids need to be exposed to these discussions because they’ll form an opinion anyway and will be exposed anyway. We can’t control what they talk or think about. Young people are far more intelligent than adults give them credit for.”

“When I first drew a nipple sticking out, I checked what people are saying to it and whether people are thrown off with something like that. But you realise over time that the threshold grows—for you and your audience,” says Harikumar referring to her journey on publishing comics on Instagram. “Everything is shameful and till someone starts to talk about it, it doesn’t change. People change the narrative. Then somebody puts out a story and it becomes okay for you to have had that experience.”

The writer is a postgraduate diploma student of journalism at the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.