Have Daily Wage Earners Been Betrayed By Biometric Authentication?

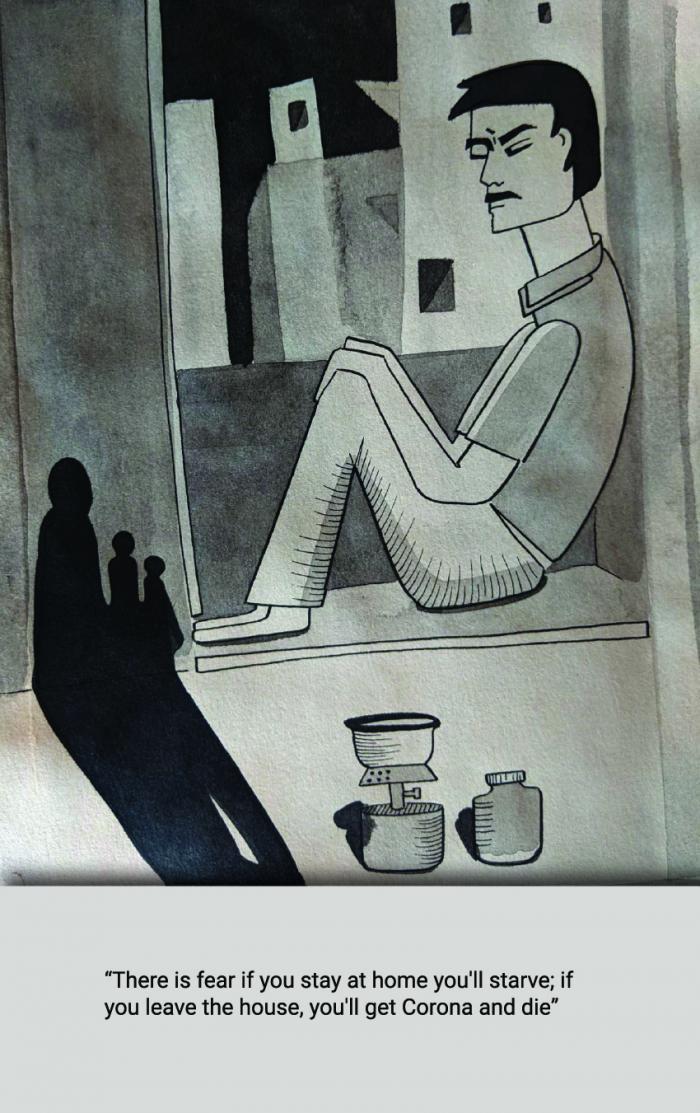

Over the past few weeks, the situation for daily wage earners has been particularly dismal. A telephonic survey with over a 100 people in rural areas of six states (Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh) by Road Scholarz, conducted in two phases (26-31 March and 4-11 April), has revealed that while most people know what precautions they need to take to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and protect themselves, knowledge alone will not keep them safe. It’s a paradoxical situation really.

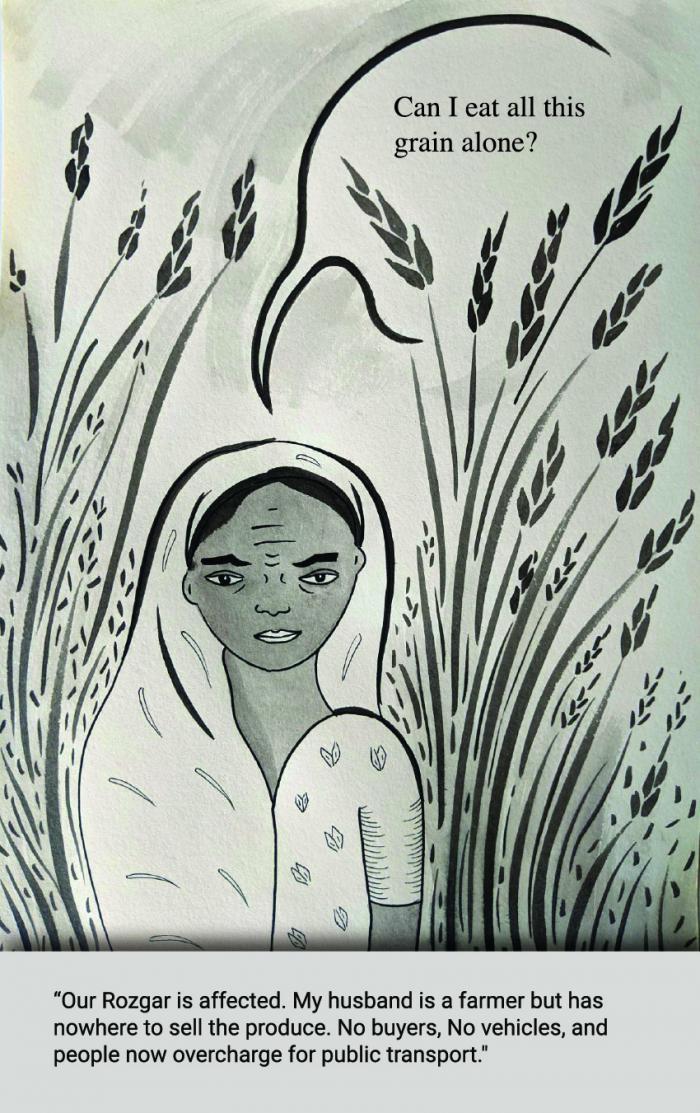

And it’s not just farmers who have been affected. Incomes have slowed down on all forms of self-employment activities –affecting, for instance, those in Himachal who run home-stays, paragliding services, taxi services, barber shops and so on.

The shutdown of public services has also meant that it has been hard to get transport to take the sick to the doctor or even withdraw money from the bank. One respondent talked about not being able to withdraw Rs 1,000 from a bank using a passbook, and another was harassed by the police when he tried to leave home to buy medicines from a chemist shop.

Many are trying to make do with what they have in store in their homes, by actually cutting down on their daily meal quotas. Some people only have food stocks to last them a week. And even if many of them do have grains or rice to last them longer, they may not have access to other food basics like vegetables, oil and spices.

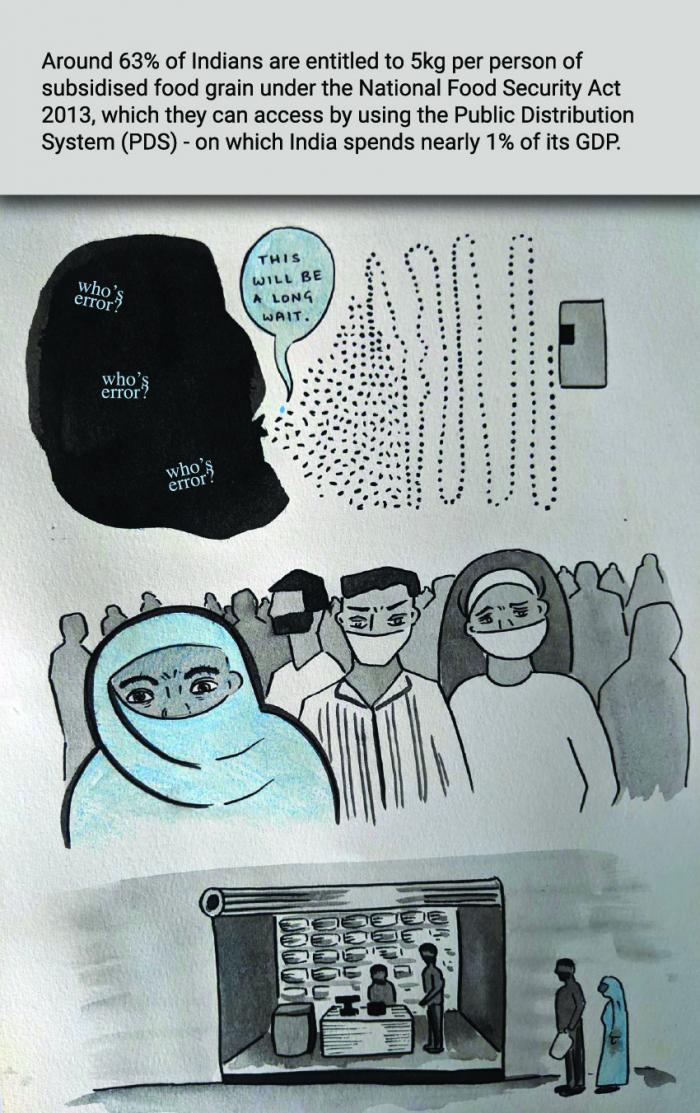

At a time like this, social security measures like the Public Distribution System (PDS), are an important source of support. Under the 2013 National Food Security Act, almost 63% of the population of India—at least 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population—is entitled to subsidised food grain of 5kg per person per month, which India spends almost 1% of its GDP on. And to tide people over due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the Central government has announced emergency relief measures of doubling the grain entitlements to 10 kilos per person, and one additional kilo of pulses, for free, for the next three months.

“However, distribution has been patchy, and some ration card holders have not received any ration for the month of April. The situation seems to be worse in Gujarat, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh.”

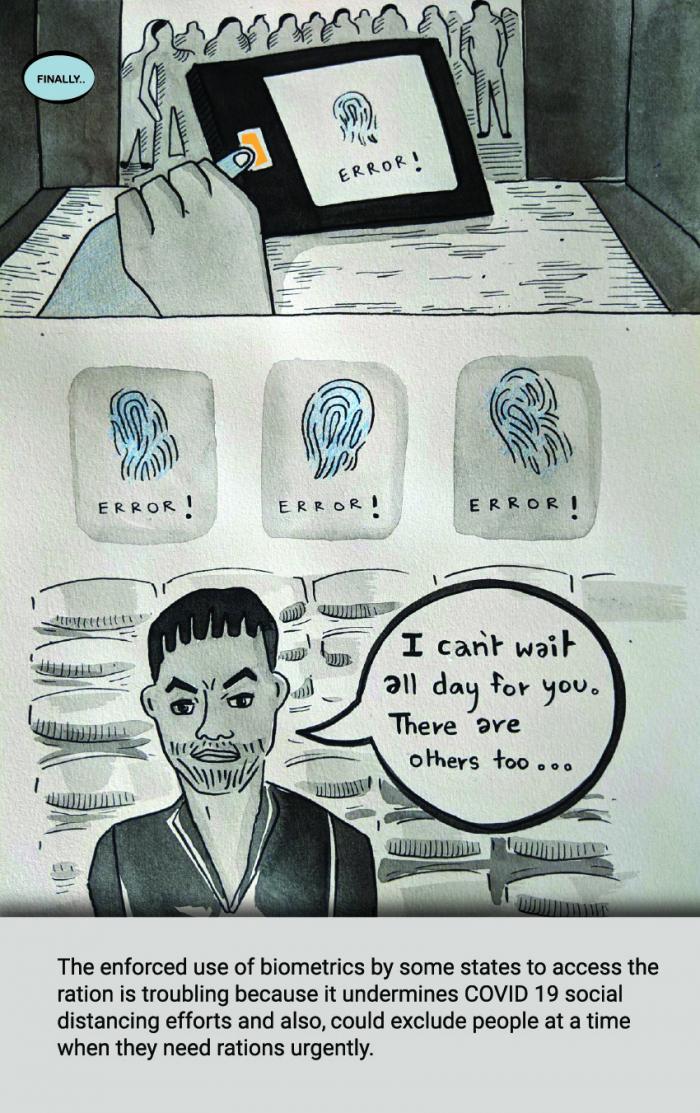

Access to these commodities has been made more difficult because of an ongoing problem with the PDS. Since 2014, state governments have made it mandatory to link the PDS to Aadhaar system, seeding the two numbers together, and mandating the Aadhaar-based Biometric Authentication (ABBA) at the point of sale. The linkage of Aadhaar to welfare entitlements was upheld by the Supreme Court in the challenge to the Aadhaar Act and project in Puttuswamy v Union of India (2019 1 SCC 1), but the majority bench of the Court also highlighted that the government had to ensure that no one was excluded because of the Aadhaar linkage or biometric failure.

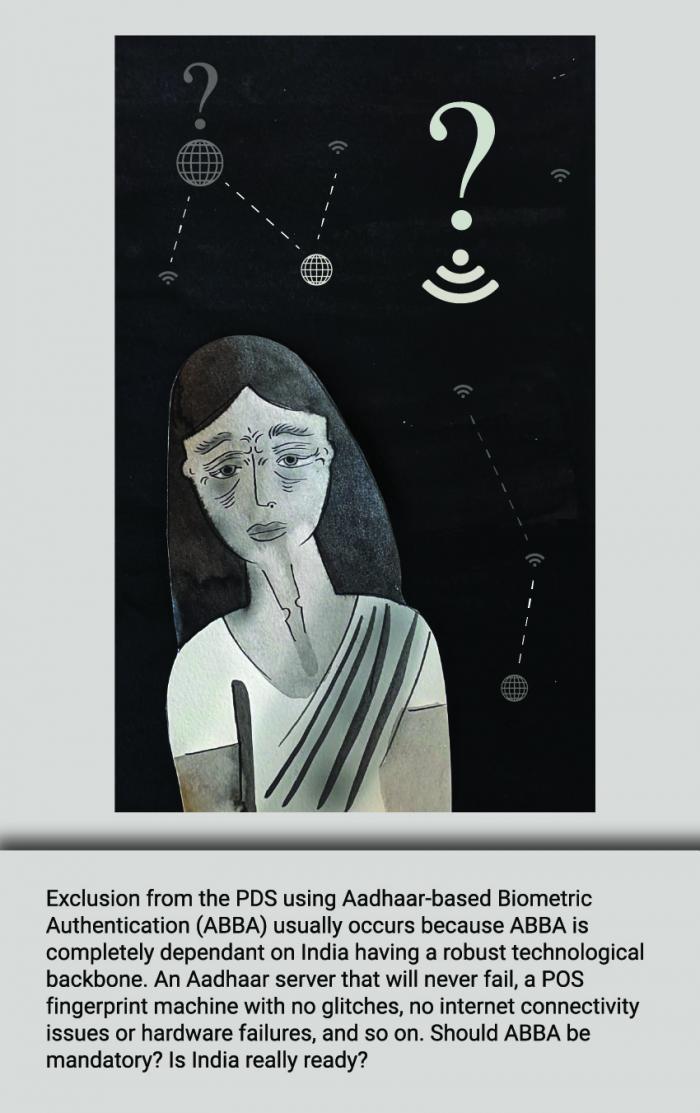

Despite this, many people continue to be excluded from the PDS system. Where previously one would just need a ration card, mandatory linkage to the Aadhaar system has meant those without Aadhaar enrolment have been left out, as only ration cards linked to an Aadhaar number are eligible for rations. The ABBA system also relies on having a robust technological backbone—an Aadhaar server that will never fail, a Point of Sale (“POS”) fingerprint machine with no glitches, no internet connectivity issues or hardware failures, and so on. So linking Aadhaar to the PDS, rather than making it more efficient and fraud free as claimed, has ended up excluding many from the system.

The reality is that technology is fallible. A survey conducted in tech-savvy Hyderabad, showed that many people faced internet connectivity issues, malfunctioning of the PoS machines, fingerprint authentication errors and so on. As you can imagine, more remote villages face significantly more challenges—this has continued to lead to a lot of exclusion, as people's names were struck off the list if they didn't have Aadhaar, or they are denied rations on the spot if their fingerprints inputted into the POS machine used for the ABBA process, don’t match with the fingerprint in the database, or if there are technical failures at any point. Thus, Aadhaar linkage limited the pool of people who can access their ration entitlements.

Additionally, using ABBA during the months India battling COVID-19, forcing people to authenticate their fingerprints on a common machine, is troubling as it can increase the possibility of COVID-19 transmission and undermines the social distancing efforts. While many states have halted ABBA for PDS for a few months, second phase respondents from Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh reported that they still had to use ABBA to authenticate their identity to access their PDS entitlements.

Given this set of situations, it is time that we reassess the value of ABBA and other biometric and tech dependant methods for the Public Distribution System—as the hurdles they place for are only exacerbated by the crisis we’re currently in.

Illustrated by Shoili Kanungo. Road Scholarz is a collective of freelance scholars and student volunteers interested in action-oriented research, socio-economic rights and related issues. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.