Why an Increase in PMAY’s Budget Shows the Scheme Has Failed

Over the past twelve months, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has been one of the most-cornered ministers of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, owing largely to her weak and often ambiguous comments on the state of the Indian economy. For her and her supporters, this year’s Union budget was meant to both rejuvenate and rekindle investor’s hopes and sentiments. The relaxation in income tax slabs was just one such incentive; a last-ditch attempt to show that all is well.

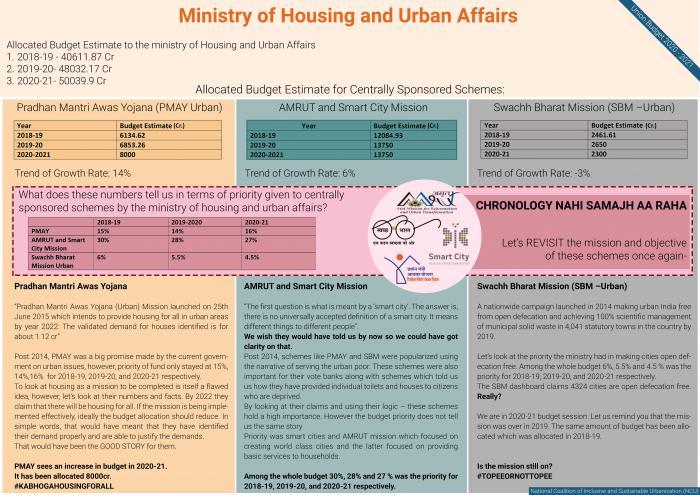

However, one sector—urban housing—has largely been left unscrutinised by the media and even in the budget speech for the 2020-21. When the Narendra Modi government came to power, it launched a series of flagship programs such as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban) Mission (PMAY), the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), Smart Cities scheme and Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM-Urban) for the betterment of urban India.

The present government has a large support base in urban India and these programs have been at the core of “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas—development for all”, the rallying slogan of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). It is a party that is liked in urban pockets and it wants to, at least through its policy moves, make Urban India a shining example of development. But it seems that the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has either not got the memo or is completely oblivious about how to go about implementing Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas.

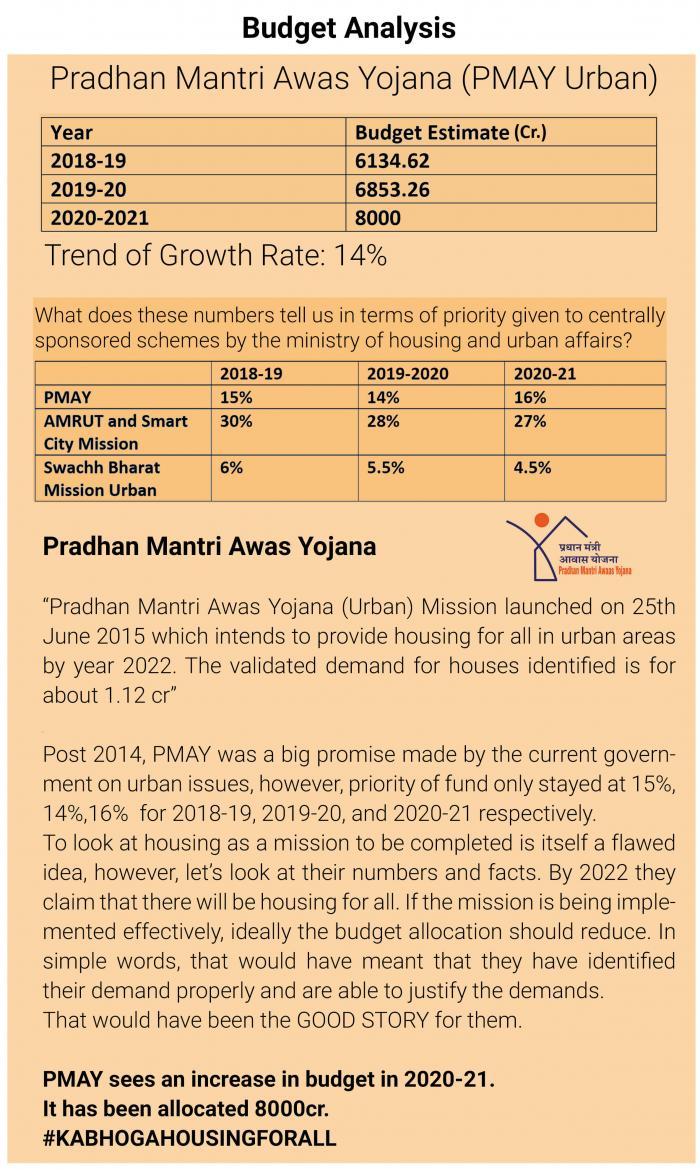

To begin with, the most important macro number from the Union budget was that the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs’ allocation rose by 4.17% to Rs 50,036 crore. The increased allocation is encouraging at first sight. Dig deeper, however, and one sees that things are not as rosy as they seem, especially in the case of social schemes.

Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (A)

The PMAY, launched in June 2015, intends to provide housing for all in urban areas by 2022. This year, the budget allocated Rs 8,000 crore to the scheme as opposed to Rs 6,853.26 crore last year. But the story goes beyond numbers: the government claims that since its launch, over 1.03 crore homes have been sanctioned by the under PMAY. However, until now, only 32.08 lakh homes have been completed and delivered to beneficiaries.

The idea of building millions of homes across the urban expanse of the nation—in just seven years—sounds appealing as a social scheme but has its share of critics. Experts argue that a ‘mission mode’ negates various important social aspects. Take, for example, the fact the demand for homes in urban spaces will continue unabated because of the never-ending migration to urban spaces, especially in light of the industrial and agrarian distress.

The number of migrants who moved from rural to urban areas stood at 52 million out of a total population of 1.02 billion, as per the 2001 Census.

Thus, the 2011 number of 78 million is a jump of 51%. The share of rural-to-urban migrants in the population rose from 5.06% in 2001 to 6.5% in 2011. How does PMAY aim to tackle this issue? We do not know, because PMAY does not divulge any information.

Instead of countering these challenges, the PMAY budgetary allocation still seems to be in the stage of identifying the timely demand (which is appreciating). There is also the question of how they arrived at 1.12 crore units as the final figure. The lacunae in the scheme show that the scheme is more about ‘claiming numbers’ than actually providing a long-lasting solution to urban residential distress.

In September 2017, the government announced eight new PPP or public-private partnership models for urban affordable housing, opening the doors for private players to the scheme. As a result, PMAY-U has a high reliance on non-budgetary funding, which has not been forthcoming. As is typical of PPP models, PMAY-U has failed to draw in private entities who are not too inspired by its profitability. The housing and urban affairs ministry informed the Lok Sabha in March 2018 that only 2.1 lakh units had been sanctioned under the component, of which some 67,000 were completed and only 43,574 occupied by the owners. Therefore, the PMAY-U started slow, and that is how things remain.

Then, there is the allocation itself. It is not often that we complain when funding increases for a social scheme, but we must take exception in the case of PMAY. It is now 2020, and we are five years into the scheme. If the allocations in previous years had done their job, the funding for this scheme should, by now, have been on a downward spiral as progress inched closer to meeting the final targets. In short, the majority of the work should have finished by now but instead, the government has achieved only one-third of their target.

It took five years to build 32 lakh homes. How does the government plan to build a further 80 lakh homes in two years? All these factors mean that the increase in PMAY allocation is more a cause for concern and queries instead of being projected as a big positive for the government’s social schemes.

There is no publicly-available data on the breakup of the 32 lakh home across the four verticals of PMAY. There is no way to access the information on the break-up of the houses built under the four PMAY verticals, namely:

-

Beneficiary-led individual house construction/enhancements (BLC)

-

Affordable Housing in Partnership with public or private sector (AHP)

Neither does the data reveal which part of the city these houses have been built in.

There is another interesting fact about the budget: it selectively hides the information pertaining to budgetary allocation of the ISSR, BLC and AHP, which are centrally-sponsored schemes.

The allocation has gone only to CLSS, another centrally-sectored scheme. In other words, funds are released by the centre and projects are implemented by the centre.

Credit-linked subsidy has been the agenda and the Centre failed on its own accord.

Only 8,02,732 households have availed CLSS subsidy benefits, at a subsidy amount of Rs 18,358 crore so far. The Centre has not been able to allocate the entire amount: only Rs 5,300 crore in the Budget for the interest subsidy. The Centre is in a fix to allocate the remaining amount and is looking at other resources to pay the subsidy amount. The measly budgetary allocation is also leading to delays in subsidy payout under the scheme, which is a cause for concern.

In theory, the PMAY is a great scheme. However, a complete disregard for actual financial details with regard to implementation and expenses, the opaque nature of policy-making in terms of region-specific demands, along with the sheer inefficiency in reaching a rather flawed target, are just some of the problems plaguing the scheme.

Sadly, an increase in the Budget allocation is nothing but an attempt to put a Band-aid on gangrene.

The author is an urban researcher who works on issues of caste and housing. She is associated with the National Alliance for People’s Movements and National Coalition for Inclusive and Sustainable Urbanisation. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.