The Anatomy of Anger and Hatred in India

Image Courtesy: North East Today

The last five years had witnessed an explosion of anger and hatred that got manifested in protests and street violence. If we are to go by even the first week of events under the second term of Narendra Modi, it evidence of what is to come. It has now become routine to describe the current times as the ‘Age of Anger’, and it has become the ‘new normal’ to witness everyday rage and hatred. However, merely brandishing these terms to randomly describe events that turn ugly and violent wouldn’t help us to make sense of what is the social content of the events that are driven by anger and hatred. Are they the same? I fathom they are not.

Anger is a symptom of a grievance and the urge for justice, while hatred is almost its opposite, born from a pervasive sense of loss of (undue) privilege and has force and intimidation as weapons. While anger is expressed by those at the lower end of the social ladder, hatred is the exclusive prestige of the privileged who don a mask of victimhood. Anger is organic, hatred is manufactured and projected. Anger establishes a sense of helplessness but does not lose hope. Hatred is born out of immunity and demands obedience.

It is, therefore, not a happenstance that two social groups and identities that have borne with both insidious and episodic violence, protest with legitimate anger but have never demonstrated brazen hatred. Dalits in India have rarely had any relief from everyday violence, organised caste massacres, humiliation and stigma. Women, too, suffer from child sex abuse, domestic violence, sexual assault, molestation in public spaces and workplace that offers them no respite. Yet, you will hardly ever witness dalits or women seething with hatred. They protest, prick your conscience, might subtly highlight your prejudices but nowhere would you have heard of dalits baying for the blood of the upper castes. They never as a rule talk of physical harm to caste Hindus. They may deny you the respect you took for granted. The women’s movement has never argued that all men need to be punished, even if they believe most men in one form or the other carry patriarchal traits within them. They express resentment and anger to bring a sense of guilt and shame. What they are fighting for is justice, not retribution.

Jyotiba Phule and Bhimrao Ambedkar, in spite of being direct victims of caste discrimination, and more so Ambedkar who was not spared of caste-based indignities in spite of his astounding achievements, was bitter, but never even as an innocuous mistake did he express hatred towards caste Hindus. He, in fact, expressed the need for solidarity if caste is to be overcome.

Phule saw the curse of caste not merely on bahujans but also on Brahmin women and Brahmin widows. The Dalit Panthers’ movement came closest to using counter-violence to overcome structured inequalities, but even they talked about all dispossessed belonging to the dalit identity. Marathi poet Namdeo Dhasal used abuse as a weapon to highlight the damage to self, yet it did not come anywhere close to qualifying as hatred.

Protests, even sometimes spilling over into violent or abusive mode, were driven by a sense of belonging, not ownership. They used abuse, as Krishna Menon, former defence minister in Nehru’s cabinet once said, ‘as a shortcut to equality`. Most feminists and women’s movements, even as they express anger and impatience with patriarchy and its accompanying violence, also argue about the damage men suffer from masculine role-play.

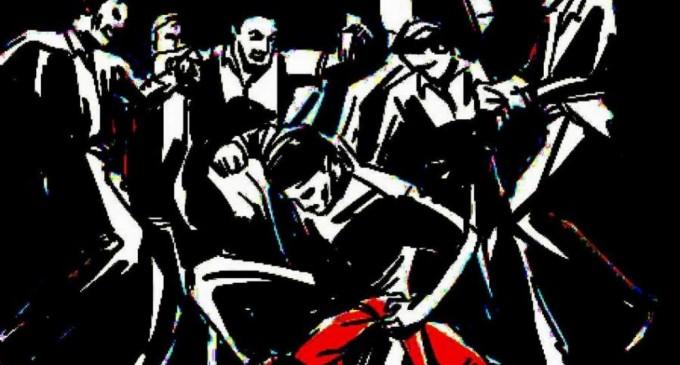

In contrast to all of this stands the hatred of the dominant groups that feel a sense of entitlement. The flogging of the dalits in Una and the lynching of Muslims in various places, is hatred born out of contempt. Hindu assertion under the Sangh Parivar, even assuming excesses by Muslim rulers in the distant past, is about bringing minorities into submission. This is born from a sense of claim and ownership over the land, not a sense of belonging and brotherhood, as is routinely claimed. It is about revenge, not about justice or dignity.

The difference between anger and hatred is at subtle display in the Kashmir Valley. The Islamic militants of Hizbul and various other outfits suffer from hatred and are driven by a sense of superiority of their religion over all other religions. They have a sense of owning Kashmir, more than loving Kashmiris, including Kashmiri Muslims.

Much in contrast, Kashmiri Muslims, who have suffered unabated violence for over half a century, continue to launch angry protests but never display hatred. A ‘Hindu’ tourist to the valley never suffers from insecurity or complaints of hatred. Kashmiri Muslims, almost always, make the necessary distinction between the Indian state and its people, even if they belong to a different religion. The most poignant and tragic case in all of this is that of Kashmiri Pandits, who suffered on account of the intolerance of militants, and remain displaced and psychologically traumatised. But what the pandits have failed to do is to distinguish between the locals and the militants. In a recent exchange on social media to a post on stone-pelters, a Kashmiri Pandit, in response to what I said, said every single protesting Muslim in the Valley should be killed. He wrote, ‘every stone pelter should be shot in the head..no questions asked..period’.

This is not an aberration; this has been my experience of most Kashmiri Pandits I get to interact with, barring honourable exceptions. Would it be legitimate to ask if Kashmiri Pandits are demanding justice or retribution? Do they claim ownership, owing to their superior social status in the past, or are they looking for a belonging that was disrupted but cannot be erased? Are they bemoaning a lost social dominance or distances created in ethnic solidarity?

Dominant social groups in India, even assuming they have some genuine grievances, be it caste Hindus, dominant intermediary castes, majority Hindu assertions or Kashmiri Pandits, need to make the necessary distinction between legitimate anger to set right history and illegitimate hatred to push back history. It is only in search for fraternity, not dominance, that hatred is seen as inimical even by and to the aggrieved.

The writer is Associate Professor, Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. He recently published, ‘India after Modi: Populism and the Right (Bloomsbury, 2018)’. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.