The Question of Testing Continues to Haunt India’s Lockdown

India’s updated Containment Plan for COVID-19 outbreaks identifies one of the key strategies as, “public health response in terms of active case finding, testing of large number of cases, immediate isolation of suspect and confirmed cases and quarantine of contacts.”

In his message to the world’s governments issued a month ago, the World Health Organisation’s Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus put it more dramatically, “You cannot fight a fire blindfolded. And we cannot stop this pandemic if we don’t know who is infected. We have a simple message for all countries: test, test, test. Test every suspected case.”

Independent experts have repeatedly emphasised the importance of tracing, testing and isolating cases during the lockdown, so that they are prevented from infecting the wider population once the lockdown rules are relaxed. After all, a lockdown only confines infected people indoors; and since no lockdown can be extended indefinitely, it can be said to fully serve its purpose – slowing down the spread of infections – only if complementary measures, like testing and tracing, are done effectively.

In its report on COVID-19 in India, the US-based Centre for Disease Dynamics Economics and Policy had warned, “A national lockdown is not productive and could cause serious economic damage, increase hunger, and reduce the population resilience for handling the infection peak”. The CDDEP instead suggests that lockdowns be guided by testing and tracing and ordered only where they are needed.

Speaking to Rediff.com, Dr Abhay Shukla, public health physician, author and co-convenor of the Jan Swastha Abhiyan or People's Health Movement, recently said, “One must understand that a lockdown is a very crude and blanket measure. It may be required for a short period of time, but it is not a substitute for individualised, very large-scale testing.”

In an interview with The Telegraph, virologist Dr Thekkekara Jacob John, a former advisor to WHO, echoed these views. “The lockdown could have this effect of confining the clusters of infections — perhaps one or two, or five or 10 persons — within households wherever they are. It is critical for the health system to pick them up effectively within the 21-day window.”

Notably, in South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong, the closest we have to COVID-19 role models, the primary means of containment was extensive testing and tracing. (As this writer had reported in an earlier article, this success was all the more remarkable for being achieved without lockdowns).

Are we testing enough?

Chiefly two types of tests are conducted to detect COVID-19 infections: Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) tests to detect presence of antigens (the virus); and serological testing designed to find the presence of antibodies (the body’s immune response to the virus).

India, which has so far mostly used RT-PCR tests, is now adding capacity for rapid antibody testing, which is cheaper and faster in comparison. As of now, the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), the nodal agency for COVID-19 testing in India, has operationalised nearly 200 government labs for testing samples for COVID-19; in addition, it has also authorised nearly 100 private labs.

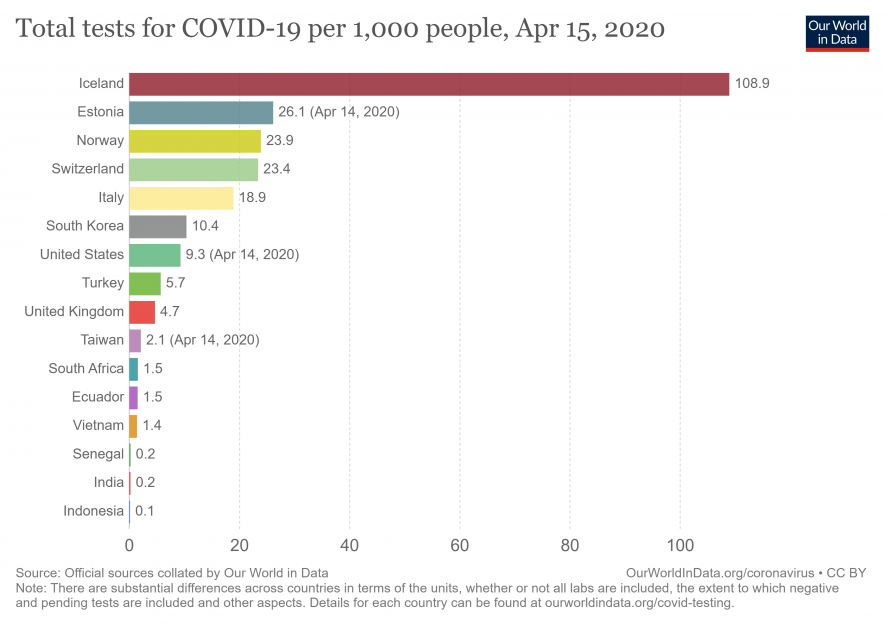

As of now, India has tested a total of 3,83,985 individuals, of which 17,615 individuals have been confirmed positive. This is a low number; for example, the US conducted 141,041 tests just on one day, April 19; itself estimated as highly inadequate by some. Once you account for its massive population, India’s test rate is one of the lowest in the world at just 0.27 tests per 1,000 people. In comparison, countries that are in a comparable stage of the epidemic like Turkey (7.14 tests per 1,000 people), South Africa (1.84) and Vietnam (2.1), are testing at a much higher rate than India.

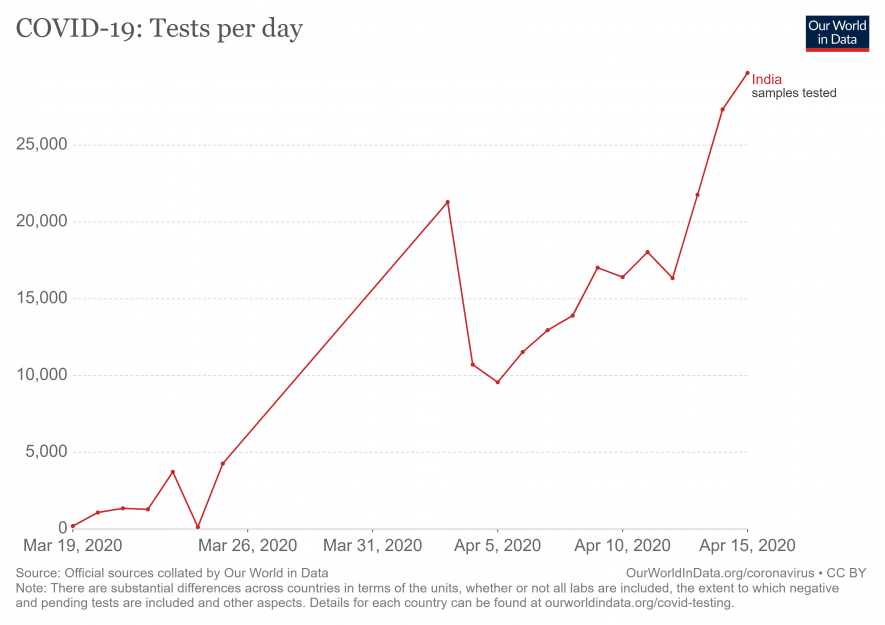

While India’s testing rate has increased since March 24, the day the lockdown was implemented, on April 3, it suddenly dipped from 21,294 tests to less than half that number (10,705 tests) the next day. It took another 10 days for testing to bounce back to the level of April 3.

At least from early March, public health experts have repeatedly called upon the government to increase testing. However, despite its renewed urgency under the lockdown, the numbers show that testing has not gone up significantly. Not just that, testing even fell sharply at one point, as seen above. Media reports indicate that this may simply be due to a shortage of testing kits.

A self-made scarcity

On March 28, Girdhar Gyani, convenor of a task force on COVID-19 hospitals set up by NITI Aayog, told The Quint that the government did not have enough testing kits, and this was why testing was low. When questioned why doctors were refusing tests to patients who had only mild symptoms, he said, “They (government) fear that these unsure cases might consume all the testing kits. That’s why they are not doing enough COVID-19 tests.”

On April 7, Jharkhand chief minister Hemant Soren told the Hindustan Times, “We got the first 5,000 test kits on April 3 and that’s why our testing has been slow. We have been repeatedly, since March 21, requesting for PPEs from the Centre. There has been an inordinate delay in getting Central help.”

On April 10, Kerala’s health minister K.K. Shailaja, told Times Now that “there is a scarcity of testing kits; of RNA extraction kits and reagents etc.”

On April 4, a week before the Kerala health minister complained of kit shortage, the ICMR had issued an advisory to states saying that it “will be approaching full capacity in the near future” for RT-PCR tests. The advisory further stated that they were expecting a delivery of antibody-based rapid test kits soon, and provided a list of 29 approved suppliers, all except one located in China.

Two weeks later, the ICMR is still waiting for its mega order of 70 lakh testing kits to come through. The critically urgent consignment, needed to ramp up testing in the 170 Covid-19 hotspots in the country, has missed five deadlines already. On April 16, the ICMR announced that it had received a smaller consignment of five lakh rapid tests, which it said was enough to meet present needs.

That may have saved the day for ICMR for now, but it cannot make up for the precious time already lost. The shortage of RT-PCR tests acknowledged in the ICMR’s April 4 advisory, which happened in spite of the extremely low number of tests that were being conducted, showed that the country was locked down without even basic COVID-19 supplies in place.

Global race, domestic farce

As early as April 3, Bloomberg reported how, as a latecomer, the Indian government was finding itself at the “back of the line” for testing kits in the global market. The report further stated that due to the shortage of kits, 123 ICMR-run labs were operating at only 36% capacity, while the 49 accredited private labs managed an average of just eight tests a day at that point.

Since then, the global race to procure COVID-19-related supplies has only intensified. As a result, state health departments in India, which were permitted to procure tests only recently, are struggling to obtain them. In one instance, 50,000 rapid tests ordered by Tamil Nadu from China was recently diverted to the US, as alleged by the state’s chief secretary. K. Shanmugam.

If international orders are not entirely in its hands, it’s the ICMR’s record on the domestic front that is truly alarming. It was only on March 23, nearly two months after India had detected its first COVID-19 case, that domestic models of testing kits were approved by ICMR.

A telling example of the confusion it created came in the form of a March 21 notification, which stipulated that testing kits produced in India needed to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. After this invited furious protests from manufacturers (one described it as “stupid”; another, as “a totally crazy move”) who accused the ICMR of discriminating against Indian companies, it was withdrawn on April 23.

What makes this episode truly astonishing is the fact that the FDA does not officially approve diagnostics even for the United States, but instead only provides ‘Emergency Use Authorizations’ so as to expedite the urgent demand for kits.

This followed in the wake of an earlier controversy, when Gujarat-based CoSara Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd claimed that it was the first manufacturer to receive approval from the ICMR to manufacture COVID-19 kits in India. As it turned out, neither the Indian company, nor its American partner behind this joint venture, had any significant previous experience in making diagnostic kits of any kind.

Double disaster

The WHO’s report on the COVID-19 outbreak in China, released on February 28, found that an overwhelmingly high proportion of infections spread in families, with nearly 80% of the clusters forming around them. The widely publicised report was the first major official study of the outbreak, and therefore the primary reference point for governments dealing with a novel virus.

Despite, this, when India declared a national lockdown a full month later, the ICMR had failed to ensure even the required supply of testing kits needed to identify suspect cases within families. If the delay in sourcing kits from abroad was a serious lapse, its dithering on domestic approvals was much worse, leading to an outrageous situation where manufacturers struggled to produce urgently needed COVID-19 test kits under the constraints and disruptions of the lockdown. Not surprisingly, these kits are yet to reach most Indian labs almost a month later.

Thoughtlessly conceived and callously implemented, India’s national lockdown has led to massive loss of life (nearly 200, by one estimate), continues to impose extreme hardship and hunger on millions, and caused long-term economic damage. Some of these catastrophic impacts were entirely avoidable; and certainly have no parallel in any other country that imposed a lockdown, whether rich or poor.

It was a manmade disaster, but since such things have always gone unpunished in India, this too will be dismissed as ‘collateral damage’ by the policymakers responsible for it. However, as the official record on testing shows, they may have botched their main mission as well.

Note: There is no publicly available data on India’s stock and usage of testing kits. Emails to ICMR enquiring about the present status of Covid-19 diagnostic supplies have gone unanswered so far.

The writer is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.