Unravelling Farmers’ Republic Day Parade One Year Later

Waiting at a desolate bus stop some distance away from the police barricades on National Highway 44, we watched vehicles hazily pass by us. Our hitchhiking attempts were failing—the tempo we had boarded at Azadpur Mandi was running on its last years and the heavy traffic at the bypass proved to be its undoing. The engine rumbled and then died with a puff of smoke. Three of us, university students wishing to be part of a historic rally, were stranded at an awkward distance between the Delhi and Singhu border, the massive encampment of farmers from Punjab and Haryana.

Half-an-hour later, a dusty nearly empty low-floor bus picked us up. The bus marshal, a retired policeman, realised where we were headed and cheekily shared that his family too would send a tractor to the next day’s ‘parade’. Surprised, we shook our heads in approval and sat. I devoured the winter sun by the window and contemplated what my return would be like the following day. It was rather hard to visualise lakhs of tractors on this patch of the highway, deserted as it seemed at the moment with the police gradually diverting traffic away from there. Nervous, I gazed at the passing fields along the old Grand Trunk Road, a route many caravans have passed through in the last millennium.

Three weeks earlier, the Sanyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM)—a rainbow coalition of more than 40 farmer unions—had declared that should the negotiations with the Centre on repealing the three farm laws fail, the movement would breach the police barricades at Singhu, Tikri, Ghazipur, Shahjahanpur and Palwal borders, and carry out a parallel farmer Republic Day parade in the national capital.

Farmers at the bustling border sites—young and old—looked forward to January 26 with a feverish desire. After more than a month of sitting patiently in the biting cold, there was finally some hope of a breakthrough on their terms.

“We had firmly decided on January 2 itself that the parade would be held 50 km away from Delhi’s centre. On the day of the parade, not a single official member of SKM crossed this line,” says Hannan Mollah, general secretary, All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), and member of SKM’s coordination committee. Looking back, he anticipated some deviations then. After all, “500 organisations were present at the borders, and it was hard to oversee everyone”. Nonetheless, the veteran leader believes that “what transpired was a conspiracy. There is no doubt”.

On the day of SKM’s announcement, I met Tejbir Randhawa, a farmer in his late 40s, at the tail end of the long line of tents and tractor trolleys at Singhu. He believed that the tractor parade would prove to be the movement’s turning point but was unsure of whether the SKM leadership would fulfil its promise. “Leader hume yahan nahi leke aaye. Hum leaderon ko yaha leke aaye hai (Union leaders have not brought us to Singhu; the masses have brought them here),” he said hinting that the same could happen on Republic Day too.

The owner of 5.5 acres in Amritsar district, Randhawa went on to say, “Don’t be mistaken that farmers have blind faith in the leadership. The spirit of the people is carrying the protest.

Randhawa did not have any union affiliation and distrusted them. But even for the majority of unionised farmers, critical junctures like an unprecedented rally in the city when all high dignitaries of the Indian state would be present was sure to bring out differences of opinion. Earlier, it was believed that tractors from all three major border sites would converge on the Outer Ring Road. The route, finalised two days before the parade while still following the Outer Ring Road, was separate for Singhu, Ghazipur and Tikri borders and did not cover the arterial road’s entire length.

Farmers decorate their tractors for the parade.

The bus had dropped us a few hundred metres from the police camp on January 25. One could go no further. To avoid a jittery police force, we sidestepped onto village roads and emerged on the other side of the line of control, right in the thick of the Singhu protest. It was unbelievably packed, and I had seen how crowded it could get there in my previous visits.

Every patch of broken asphalt along the entire length and width of the highway was occupied by farmers, listening to speeches, huddling together and raising slogans, flaunting their tractors, buying protest goodies from hawkers, getting refreshments, decorating their tractors with flowers and glace paper, and taking selfies. It was a sight to behold.

The three of us headed to the AIKS tent, where we had planned to spend the night before launching off on one of the tractors. We were reunited with Gulab Singh, our sole contact in this sea of lakhs. Singh, a daily wager from Panipat, was responsible for managing the affairs there. The tent was at the diametric centre of the two landmark protest stages at Singhu. Two stages had been set up—not out of some pragmatism given the lack of space but because of unbridgeable political differences. The smaller stage was occupied by Kisan Mazdoor Sangharsh Committee (KMSC), led by Satnam Singh Pannu; the bigger one was animated with supporters of the various unions under the SKM. Both looked away from one another.

Hannan Mollah points out how when farmers reached the Singhu border following the ‘Delhi Chalo’ call, the police barricaded it with a layer of shipping containers, concrete slabs and barbed wire.

“How then did Pannu’s group, which arrived 10 days after the SKM, set up their stage across this layer of barricades? It seems to me that the government perceives Pannu as their damaad (son-in-law) and placed them ahead of us,” a surprised Mollah says. “From there, he would daily give speeches inciting farmers to lay siege to the Red Fort on Republic Day and spill blood.” While this occurred right next to the police camp, it is striking that the forces remained passive.

KMSC was not the only outfit opposing the SKM’s proposed parade route. There were others, like Rashtriya Kisan Majdoor Sangathan’s Sardar VM Singh, who was quoted saying a day before the rally, “What is the point in having the parade on a road where no one can be seen around. Our boys are charged up and they won’t accept such routes.” The recalcitrant Singh had been removed from the SKM in December 2020.

Then there were upstarts like Deep Sidhu and Lakha Sidhana who, coming from questionable backgrounds, had carved a space for themselves since the protests first started in Punjab in September. Their existence points not so much at the SKM’s failure to bring everyone under the same banner but instead to a much simpler fact: all mass movements inevitably carry all shades of rigid opinions within themselves.

We spent the afternoon having lunch at the ‘Guru ka Langar’ (equipped with an automatic roti maker) and walked around to get a sense of the protesters. One farmer claimed that tractors had clogged the 60-km road connecting Singhu to Panipat. It was hard to imagine the tsunami of people converging here.

As evening fell, we returned to the makeshift tent, where we met Kawaljeet Kaur, who had arrived along with her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren. A member of a women’s organisation, she firmly believed in revolutionary politics during her graduation days. Before she left, we shared our contact numbers though I did not expect to hear from her again. But just before midnight, she called me once to check whether I was safe: she had heard on social media that some ‘unruly elements’ had captured the main stage and were inciting the youth. Was the cat out of the bag? I wondered. It all started around 8 pm at the SKM stage.

We had taken Gulab Singh’s leave to have dinner and, if lucky, some sweets. The mercury was dropping gradually but the site bustled with farmers walking in and out of the site. Soon, we realised that many of them were rushing towards the SKM stage; we too followed.

Under the massive shed erected on steel columns, stood thousands of young men keenly watching the loud spectacle on the stage. I could feel the weight of the crowd trying to push its way further inside to get a better glimpse. The SKM stage, otherwise an orderly dais with a moderator managing the affairs strictly, was the most chaotic sight that particular night.

There must have been a hundred people on the stage itself— all huddled around the mic. The energy was insane; not a single minute passed without the slogan of ‘Waheguru ji da khalsa, Waheguru ji di fateh, Jo bole so nihal, Sat sri akal’ reverberating in unison.

Now, different unknown men who were not SKM representatives started harping on the mic about the parade route with some favouring it and others calling it a betrayal. The young farmers were agitated especially after Deep Sidhu was pulled down from the stage minutes ago for provoking the crowd against the SKM. There was still some apprehension as to what everyone wanted to hear. The sentiment, however, was clear: “Our month-long wait must not be an eyewash tomorrow.”

Then a man in blue tracksuit emerged on the dais. The cheering suddenly intensified. Out of curiosity, I asked a farmer beside me sticking his neck out for a better view about the speaker. “Lakha Sidhana,” he responded. With the mic firmly in his grip, he told the young men: “Tussi Jithe Kahoge Uthe Jawange (We will go wherever you want).” The audience rose in delight feverishly clapping and raising another round of slogans. Everyone’s faces lit up. Perhaps, Sidhana had said enough without being verbose. At this moment, the three of us, swayed by the flux of energy around us, cheered on too believing that this direct bypassing of SKM’s decision was necessary.

Slowly, the crowd started dispersing. Some old greybeards who had been listening to the rabble for the last hour in one corner seemed lost and unable to process the sight of young men of the movement taking the mantle so bluntly. I started feeling doubtful? Who was this man and why did everyone accept his call to disobey the SKM?

Lakha Sidhana speaks at the SKM stage.

“Our objective was not to cause a ruckus but to send a message (to the government),” says Yudhvir Singh, general secretary, Bharatiya Kisan Union (Tikait) when I asked whether the parade route could have been adjusted to enter Delhi further inside. “After brainstorming, we decided on routes that would avoid confrontation and not affect normal life in the city. But most importantly, we chose these routes because otherwise three lakh tractors would get stuck in a traffic jam of their own making. We never said anything about the Red Fort or about disturbing the military parade,” he says admitting, however, that “it is possible that some people misunderstood us.”

This misunderstanding, however, was not born out of a lack of proper communication from the SKM but through deliberate attempts by factions who had failed to find space within the coalition earlier, believes Mollah. “Some people from Punjab wished to appear more militant than the SKM to gain followers among the youth. So Deep Sidhu and others tried to capture the main stage several times throughout January.”

Unlike previous times, the rebels did seem to be finding a lot of relevance on the night before the parade capitalising, perhaps, on a genuine resentment among young farmers.

Jagjit Singh Dallewal, state president, BKU (Sidhupur), says that the SKM attempted to talk things over with opposing factions. “In Chandigarh, we had a meeting with Deep Sidhu after which he declared his support to the SKM at a press conference. Later that night, however, he announced launching a parallel protest programme at Punjab-Haryana’s Shambhu border. Even after we reached Delhi borders, he had separate plans. As far as the youth are concerned, the SKM had meetings on how to control them during the parade. But the government had laid a trap and our youth got lured into it.”

Farmers head to their tents after a chaotic evening.

Returning to our tent, we met a 20-somemthing Balsharan Braich, a native of Ludhiana district who was to pilot one of the AIKS tractors. Otherwise a cheerful guy, he was visibly upset and tensed. Even before I could ask, he shoots off how Sidhana is a gangster-turned-‘social activist’ who had captured the imagination of young men with his brazen show of gun culture much before the movement began.

The mass movement had attracted, besides its core base of farmers and labourers, other sections of Punjabi society. Ethnonationalists and former criminals like Sidhu and Sidhana were present as well.

The older farmers understood unionism—most of them had been part of some union since the Green Revolution changed the socioeconomic landscape of Punjab and Haryana. On the other hand, the relatively inexperienced younger ones did not have unassailable faith in the SKM’s decisions and accepted Sidhana’s call.

Not all young men, however, had been carried away. Balsharan, cadre of a left-wing organisation, categorically supported his union’s orders. “It took us two months (from September 2020) to build this movement. We knocked on every door to mobilise villagers. I myself go home once in every 15 days and have spent more than Rs 2 lakh. I am willing to die for the movement but on my union’s orders.”

The anxious night, which passed without another major incident, nonetheless saw small groups of young farmers briskly marching across Singhu shouting, “Parade road, Ring Road!”. Parade karange, Ring Road te.” Very few farmers were asleep in their trolleys and tractors. The agitators made sure to constantly barrage them with calls to disobey the SKM. The effects of this would boil over the next morning.

Tractors parked in front of the KMSC stage.

By 4 am, tractors were being squeezed through the narrow spaces and brought to the front. Amid the dense fog, farmers were wiping copious amounts of dew off the bonnet and cold-starting the engines. The exhaust from the engines warmed the air around us bringing much relief in the bitter cold.

As soon as the morning light broke, farmers hurriedly started giving decorations on their tractors a final touch. Almost every machine hoisted the national flag and the union flag on its chassis. Equipped with stereo systems, farmers played protest songs like Kisan Anthem, Pecha, Modi Ji Thari Tob Kade Ham Delhi Aage and waited with their feet on the clutch pedal.

Amid the flood of tractors, we met Harvinder Singh of Kirti Kisan Union from district Moga. He had spotted the AIKS badges pinned on our chests and gestured to shake hands with us. “I see that you too belong to the red flag,” he remarked with a smile. Unperturbed about the events of last evening, he was sure that most farmers would go by the SKM’s decision.

And yet, as things were, the SKM’s mobilisation was behind KMSC. Despite having relatively lesser numbers, the KMSC would still be the first to break the police barricades and launch off towards Delhi.

Around 7 am, we began hearing a chorus of sounds from near the KMSC stage. Crossing the stables of the Nihangs, what we saw remains etched in my mind. Thousands of farmers were spiritedly removing every layer of the barricades with sheer Herculean force. Agitated by the loud, crashing sounds of barricades being pulled down, the horses started neighing nervously.

To get a better view of the spectacle, men had climbed onto buildings on either side of the highway and the ship containers. With some help, I was able to push myself up one container and saw the pace with which the road was being cleared. The star of the show, a JCB picking off thick concrete slabs and pulling ship containers away, caught everyone’s imagination. Each time a slab was thrown into a ditch, barricade torn away or a shipping container flipped, thousands would clap and shout slogans celebrating the moment.

The police stood by. A three-star police officer who signalled the JCB driver to exit the vehicle was squarely ignored cheered on by the spectators. Twenty 20 minutes, the same officer hugged some Sikhs. “Take it all away!” he seemed gesture.

A JCB clears the Singhu border barricades on the morning of January 26.

With the highway wide open and the horizon clear, the tractors, with each carrying 5-10 people, started moving out by 9 am with the KMSC vehicles leaving first, followed by the Nihangs and the massive SKM contingent. Farmers who stayed back waved and cheered. In the brief moment without police hindrance, the public had reclaimed the ‘Republic’.

We were lucky enough for a generous Balsharan to allow us on his rather packed green-coloured tractor. After some near-misses between the rear wheel and my sorry feet, I was able to perch myself on a safer spot. Our perilous journey had begun.

From the moment we left Singhu till the bypass on NH44, where everything came to a halt, the parade was properly managed and supervised by thousands of SKM volunteers. Running in between vehicles, they were updating the farmers about the route, throwing water pouches and handing bread pakoras and plates of hot khichdi. Indeed, a struggle cannot be won on an empty stomach. With this philosophy, the unions showed acute coordination and a sense of responsibility for each protester heading towards Delhi.

Initially, it was easier for the volunteers when the tractors were following a single lane. But soon, with a bottleneck popping up on our rear, farmers had no choice but to spread out. By the time we crossed Alipur, we could see tractor trolleys, four-wheelers, SUVs, motorbikes, trucks and even bicycles everywhere. On top of one of the SUVs passing by us was Kanwar Grewal, a hugely popular singer from Punjab singing his hit protest songs to boost the morale of the protesters.

On way to Delhi.

About 15 minutes before reaching the bypass, a major junction where sections of the highway diverge towards different parts of the city, we started receiving panic calls from friends who knew we were part of the parade. TV channels were showing visuals of the police firing tear gas and beating up protesters near the bypass, they said. We shared the news with Balsharan, who nodded his head to signal that he had heard us but was stoic enough not to say a word. We dialled a few numbers to confirm the news while swinging back and forth as the tractor sped up on the highway’s last stretch.

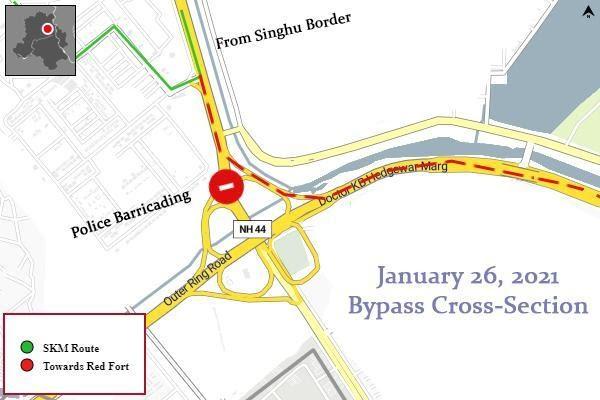

Soon, everything came to a grinding halt. The bypass was a theatre of sorts. While the police blocked the highway with riot vehicles, water cannon trucks and hundreds of armed personnel, the authorities had conveniently left wide open two exits—one on the right led to Sanjay Gandhi Transport Nagar, part of the SKM’s decided route, and the left was towards ITO and the Red Fort. In this rather Robert Frost-esque situation, it was up to farmers to take the final call. The KMSC leadership had already taken the left exit whereas SKM leaders like Balbir Singh Rajewal who were only minutes away had yet to cut through the dense gridlock at the bypass to remind farmers to follow the decided route.

Some abettors, possibly Sidhana’s men, were shouting “Dilli, Lal Qila!” from the left flank of the highway’s cross-section. For a while, everyone waited with each tractor halting edge to edge. When a few started moving left, those right behind them had only a brief moment to decide.

At this moment, the sentiments of the previous night and the present confusion crystallised. Balsharan made frantic calls to AIKS leaders for their final word. They said: “Take right and follow SKM’s route.” And he did. A column of tractors followed us and within minutes, the SKM leadership made it to the front. But the damage had been done: all this while, hundreds of tractors had taken the left exit oblivious of the consequences. This contingent, only a minor part of the humungous rally, would nonetheless go on to reach the heart of the national capital with the vultures of the mainstream media waiting to pick on them.

A section of farmers who took left at the bypass move towards central Delhi.

“Whenever the government organises the military parade on Republic Day, it deploys 50,000 security personnel to manage a tiny audience. Our parade had lakhs of participants. Even then, despite assurances from the police regarding the guidance with the route, what we saw was an eyewash presence,” remarks Yudhvir Singh with a sigh adding, “This government has perverted minds; they can go to any extent to maintain their rule.”

A year has passed since that eventful day, which saw both the highest and lowest ebb of the farmer movement. Victory embraced them in the end but more than 700 farmers had lost their lives in the long bitter struggle.

When I ask SKM leaders how they would assess the tractor parade, they differ. “It was a sad day. We were going to make history with the Kisan tractor parade; even the Guinness Book World Records would have noted it. Log humari misaal dete (People would have given our example). Even the people enthusiastically came on the streets and showered flowers on the farmers. But we got stuck in a government trap and failed. I will regret it my entire life,” says Yudhvir Singh striking a sombre note. Dallewal adds that “Bhaisaab [Yudhvir] is correct. Everyone feels this way. If we had succeeded, the world would have known about our feat."

Mollah, on the other hand, sees the parade as a crucial moment “that turned public favour perfectly in favour of the farmer movement in the long run”.

Either way, the disarray that farmers found themselves in the aftermath of the parade made them realise the necessity of discipline in a mass movement and putting up a united face. This, no leader will deny, was the most outstanding contribution of the historic rally of millions in the national capital.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.