Why Gyanvapi Case Reminds of ADM Jabalpur

Hope fate will protect Justice DY Chandrachud from regretting the Supreme Court order that he and two other judges—Justice Surya Kant and Justice PS Narasimha—recently passed in the Gyanvapi mosque case. Yes, in much the same manner as his father YV Chandrachud repented his verdict in ADM Jabalpur.

Delivered on 28 April 1976, veritably the peak of Prime Minister India Gandhi’s brutalisation of India, YV Chandrachud and Justice PN Bhagwati were two of the four judges who upheld the government’s claim that when fundamental rights are suspended during an Emergency, a person cannot approach the court even when unfairly detained. The sole judge who dissented was Justice HR Khanna.

In later years, both YV Chandrachud (hereafter, Chandrachud Sr) and Bhagwati regretted the ADM Jabalpur verdict. Of the two, the position of Chandrachud Sr in ADM Jabalpur flowed, as he made it very clear in an interview to constitutional historian Granville Austin, from his philosophical view of the Indian Constitution.

To begin with, Chandrachud Sr, in a speech to the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, on 22 April 1978, explained the position he took in ADM Jabalpur. He said, “I regret that I did not have the courage to lay down my office (sic) and tell the people, ‘Well, this is the law.’”

He explained his FICCI speech more cogently in an interview to Austin in 1994, nearly a decade after demitting the office of Chief Justice. Austin writes, “Justice Chandrachud [Sr] continued to hold to his belief that for Indians there was neither natural law nor pre-constitutional rights. If the freedoms in the Constitution are suspended, then they are suspended, he said. ‘In the Habeas Corpus case [as ADM Jabalpur is also known], I should have gone against the law.” (Page 342, Working a Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience; author: Granville Austin) In other words, he should have resigned from the Supreme Court, as he had told the FICCI audience, than uphold the law.

Chandrachud Sr’s comment to Austin underscores a telling point: when the Constitution and laws hinder doing justice to the people, the right course for a judge is to quit his post.

In 2017, in the KS Puttaswamy case, a nine-member bench unanimously ruled that the right to privacy is a fundamental right. Justice DY Chandrachud (hereafter, Chandrachud Jr.), in his judgement, wrote, “When histories of nations are written and critiqued, there are judicial decisions at the forefront of liberty. Yet others have to be consigned to the archives, reflective of what was, but should never have been. ADM Jabalpur must be and is accordingly overruled.”

Later, in a lecture on Freedom as Art in Mumbai, Chandrachud Jr said, “I know he [Chandrachud Sr] believed through his life that ADM Jabalpur was wrong.”

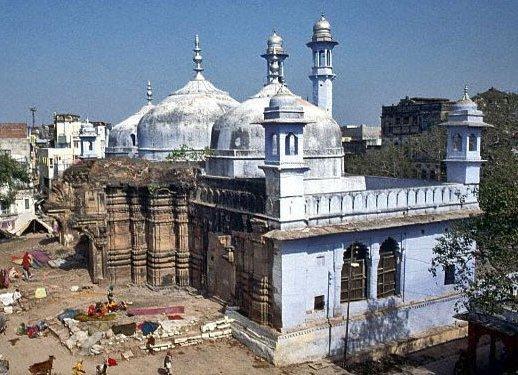

The Gyanvapi Mosque

Cut to 2021. Five women filed an application in a civil court in Varanasi requesting that they be allowed to worship Maa Shringar Gauri Sthal located on the outer wall of the Gyanvapi mosque. The court, in May this year, ordered a survey of the mosque and asked him to file a report, the contents of which were leaked. A shivling is claimed to have been located in the hauz or pond meant for wuzu or ablution Muslim do before offering namaz or prayer.

Although Muslims countered saying the shivling was just a fountain, as is found in several mosques built centuries ago, as this story points out, a frisson of excitement swept Varanasi. Hindus flocked to the Gyanvapi mosque, as also did Muslims in an obvious attempt at counter-mobilisation.

Meanwhile, the Committee of Management of Anjuman Intezamia Masjid, responsible for the upkeep of the Gyanvapi mosque, moved the Supreme Court that the proceedings in the Varanasi court were in violation of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991. Its lawyer, Huzefa Ahmadi, argued that since no relief can be given to the women under the existing law, the women’s plea should be rejected under Order 7 Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

No relief could be given to the women, Ahmadi argued, because the Places of Worship Act, 1991 freezes the religious character of places of worship as it existed on 15 August 1947. For sure, any piece of legislation can be amended by Parliament.

However, the 2019 Ayodhya judgement, unanimously delivered by a bench of five judges, including DY Chandrachud (hereafter, Chandrachud Jr), elevated the Places of Worship Act to the status of those legislations that reflect the basic features of the Constitution, as Sriram Panchu, senior advocate and mediator in the Ram Janmabhoomi dispute, points out in this interview to The Print news portal. Parliament, as the Supreme Court has said, can amend the Constitution but not its basic structure.

An analysis of the Ayodhya judgement establishes how the status of the Places of Worship was elevated.

The Ayodhya judgement says, “The Places of Worship Act imposes a non-derogable obligation towards enforcing our commitment to secularism under the Indian Constitution.” The term non-derogable means certain rights are inalienable and cannot be infringed, regardless of the circumstances, including war.

The Ayodhya judgement goes on to say, “The law [Places of Worship Act] is hence a legislative instrument designed to protect the secular features of the Indian polity, which is one of the basic features of the Constitution.” It then adds, “Non-retrogression is a foundation feature of the fundamental constitutional principles of which secularism is a core component.” The term non-retrogression means a right once bestowed upon the people cannot be diminished or extinguished.

The Ayodhya judgement concludes its analysis thus: “The Places of Worship Act is thus a legislative intervention which preserves non-retrogression as an essential feature of our secular values…. In preserving the character of places of public worship, Parliament has mandated in no uncertain terms that history and its wrongs shall not be used as instruments to oppress the present and the future.”

What noble sentiments those, expressed so beautifully!

Two Generations, Same dilemma

The nobility expressed in the Ayodhya judgement has been matched by the brilliance of Chandrachud Jr, who perceived in the Places of Worship Act a lacuna none had seen in its 31 years of existence. To the argument of Huzefa Ahmadi, son of former Chief Justice AM Ahmadi, that the Places of Worship Act rendered the suit in the Varanasi court non-maintainable, Chandrachud Jr countered that the “… ascertainment of the religious character of a place is not barred by…the Act.”

Chandrachud Jr then cited a parallel, which, because of its sheer logic, has had many to go, OMG! “Suppose there is an agiary (fire temple). Suppose there is a cross in another segment of the agiary in the same complex… Does the presence of the agiary make the cross an agiary? Does the presence of a cross make the agiary a place of Christian worship... What does the Act therefore recognise? That the presence of a cross will not make an article of Christian faith into an article of Zoroastrian faith, nor does the presence of an article of Zoroastrian faith make it an article of Christian faith,” Chandrachud Jr said.

Indeed, the Places of Worship Act does not debar religious ascertainment. The interpretation of Chandrachud appears to be legally right, as his father, from his perspective, was right in believing what he did in 1976—and which he later came to rue.

As a matter of fact, the Places of Worship Act does not even allude to ascertaining the religious character of a temple or a mosque or whatever, perhaps because Parliament never thought the need for it would arise. To figure out Parliament’s thought readers need to ask the question: Why would anyone need to ascertain the religious character of a place?

One compelling reason could be to determine the historicity of a structure. But it is already well documented that Mughal emperor Aurangzeb demolished the Vishwanath temple in 1669 and built the Gyanvapi mosque. The Vishwanath Temple was reconstructed in 1780, next to Gyanvapi. None of the five women is either a historian or an archaeologist. Their plea in the suit is that they be allowed to worship Maa Sringar Gauri in the Gyanvapi complex. Their plea does not express a historical interest in the complex.

The ascertainment of the religious character of the Gyanvapi mosque is, thus, linked to the claims of five Hindu women to it. Obviously, we cannot prejudge the pronouncement of Varanasi’s district court, to which the suit has now been referred.

Yet the experience of the Babri Masjid controversy has also to be reckoned with. Ever since a claim was made on the Babri Masjid in the 19th century, on the grounds that it was the very spot where Lord Ram was born, judicial pronouncements, spread over a century, only expanded the rights of Hindus to it, an account of which can be read here.

During the next eight weeks, the period during which the district court is supposed to deliver its verdict, the belief that there is a Shivling in the Gyanvapi mosque will harden. A Mathura court has now said that the Religious Places of Worship Act does not bar a plea against the 1968 agreement between the SriKrishna Janmabhoomi and the Shahi Idgah over there. Such disputes over places of worship will likely now surface countrywide.

It can, obviously, be argued that the battle between the votaries of composite nationalism and those espousing Hindutva should be fought in the political arena, not in courts. But when disputes over mosques acquire judicial validity, in violation of the Places of Worship Act—and that, in turn, tacitly encourages copycat acts elsewhere in the country—there would be very little to fight over in the political arena. What then would be left for us is to lament the remains of the Republic—and watch the retrogression of the Constitution.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.