Woman of the Street

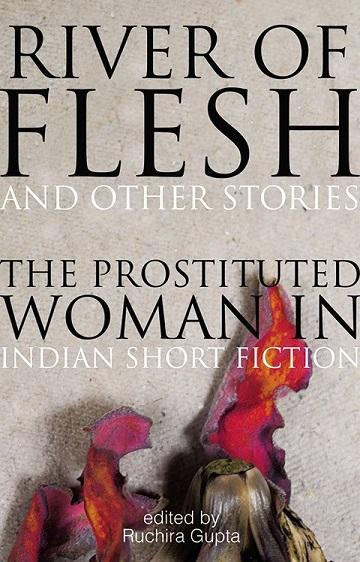

Image courtesy Speaking Tiger

Ruchira Gupta's River of Flesh and Other Stories: The Prostituted Woman in Indian Short Fiction brings together twenty-one stories about trafficked and prostituted women by some of India’s most celebrated writers — Amrita Pritam, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Indira Goswami, Ismat Chughtai, J. P. Das, Kamala Das, Kamleshwar, Krishan Chander, Munshi Premchand, Nabendu Ghosh, Qurratulain Hyder, Saadat Hasan Manto and Siddique Alam, among others.

An unprecedented anthology—for its subject, as well as for the range of authors and translators who are part of it — the book offers a harsh indictment of this practice of human slavery, too often justified—and occasionally glorified—as the ‘world’s oldest profession’.

The following are excerpts from the Introduction and Baburao Bagul's story in the book.

The idea for River of Flesh and Other Stories germinated five years ago over a conversation with my friend Rakhshanda Jalil. I was talking to her about the roadblocks I faced when I tried to make people understand that prostitution was not just a function of women’s inequality, but that it actually deepened women’s inequality.

Wherever I travelled, I came up against the word ‘agency’. I was told that some women choose prostitution over marriage, that they find freedom from patriarchal structures in prostitution, that college girls prostitute themselves for the sake of consumerism— to buy shoes, lipstick, bags, clothes, perfume… I was also told that prostitution was a livelihood choice many women make when confronted with sweat-shop work, domestic servitude and oppressive marriages.

As an activist, organizing girls and women suffering from inter-generational prostitution in red-light districts and caste-ghettoes, the reality I saw was vastly different. I witnessed prostituted women struggle to access even their most basic needs— food, clothing, shelter and protection from violence. I saw women live and die in debt bondage. I came to know of the huge profits which pimps and brothel-keepers make. I saw girls and women chewed up and spit out by the brothel system. I met women in their early thirties who had been thrown out of brothels because they were no longer commercially viable—customers constantly demand ‘fresh meat’.

The average age of a girl pulled into prostitution is between nine and thirteen years. Ice is used to physically break pre-pubescent girls and make them amenable to exploitation. They are put through a process known as ‘seasoning’, in which they are beaten,

starved, drugged, told to call their pimp ‘Papa’ and their brothel-manager ‘Ma’ or ‘Masi’, and made to believe that they are repaying the small loans of five or ten thousand rupees which their fathers have taken. These girls are raped by eight to ten customers every night. They are made forcibly available to customers at any time, day or night. They have to stand on the streets for long hours to attract customers for themselves or for older women. They suffer from sleep deprivation, insomnia and aching legs.

I saw mutilated bodies, bottles shoved up vaginas, scars of cigarette butts on breasts, repeated fractures, suicides and murders. I saw pimps and brothel-managers beat women black and blue for talking to other girls or for simply crying. Many suffered from Stockholm Syndrome, and were grateful for small acts of kindness by their kidnappers.

Almost everyone had normalized the violence to such an extent that, if asked, they denied having faced any. For the women, the violence inflicted by the customers upon them was paid for, and thus couldn’t be defined as such. However, according to current research, the physical and mental consequences of the repeated body invasion that prostituted women face is so extreme that these girls and women suffer from higher rates of psycho-social trauma than even war veterans.

I saw little ‘agency’ in their lives.

Yet, I have heard smart men—and smart women, too—say that prostitution is empowering and not de-humanizing; that it is one livelihood choice among the other unequal choices available to women. Some even say it should be defined as work like any other and prostituted women should be called ‘sex-workers’.

I cannot tell whether these men and women are protecting the status quo or just have no faith in anyone’s ability to change it. Do they, by accepting prostitution as inevitable, accept women’s inequality as inevitable? When they said that women prostitute themselves, did they mean that these women have sex with themselves? Why do they negate the role of men? Perhaps the problem is that they do not want to address the issues of male power and privilege. So, as long as men hold on to power and entitlement, my friends are happy to let women settle for ‘agency’ within deeply exploitative systems…

Over the twenty-one stories in this collection, a system of abuse by customers, pimps, brothel-keepers, lovers, husbands and recruiters is delicately uncovered.

The term ‘sex-worker’ cannot erase the trauma of body-invasion. Nor can any kind of legislation do away with the shock of body-penetration. There is no glossing over the fact that prostitution is an inherently exploitative practice, more akin to slavery that to occupation. As a feminist and campaigner for social justice, these stories, as well as the lived experiences of the women I meet, have only strengthened my belief that women do not choose prostitution, they are prostituted. River of Flesh and Other Stories: The Prostituted Woman in Indian Short Fiction is our attempt to de-normalize the efforts to legitimize the exploitation of women.

Girija had visited Haji Malang at night. In the morning, as soon as she woke up, she distributed Baba’s prasad to all in the shanty town who would accept it. Then she left for her breakfast. She was still carrying some prasad to give to people she would meet. After breakfast she was going to go up the hill to wash her soiled clothes, to scrub down her body with coir and soap. In the evening she would set off for business, chewing paan. She was going to rake in the money. She was no longer afraid of the new girl. She had asked Baba to ensure her success and made him responsible for bringing ruin upon her rival. Everything was going to turn out according to her wishes. She had the support of so many fakirs’ blessings. She had fed one of them for two days. Done charity with an open hand. Offered a chaddar to Baba. She had done all that was demanded of the faithful. She was certain that her faith would guarantee good business for her.

Knowing this, she went tripping up the steps of the restaurant, laughing, glittering and calling out, ‘Kassam, come get your prasad’. The owner, fed up of giving her credit, told her to come to him. But she didn’t budge from her chair and instead called out her order loudly. The owner was enraged to see the flurry she was in. He shouted, ‘There’s a telegram for you.’

When she heard this, she shoved her chair back with a bang and shouted, ‘Telegram!’ The restaurant owner calmly explained the telegram to her in Marathi. She heard him and howled. She fell at his feet instantly, begging him to lend her money to go to the village. Not in the least bit moved by her pleading, he said, ‘I kept your telegram for two days. I didn’t throw it with the waste paper. Another thing. I gave a woman like you an address. I’ve given you a lot of credit. A lot of credit. Go now. I’ve done enough for you.’

She left without a word. There was a surging lava of grief in her. Every cell in her body was numb. Even then, she began to get ready. She rubbed soap into her face and scrubbed it. She wiped it dry with a used choli. She brought a mirror up to her face. Then the sob that had been heaving in her body, repressed, now broke loose. The mirror fell from her hand. She wept till she grew calm. Once again, she sat down to adorn herself. She oiled her hair and parted it. She made a loose bun on the nape of her neck to make her face look attractive. She pulled out a tendril of hair and let it hang down against her cheek. She etched a kumkum spot on her forehead. She took off her choli, pulled the edging and stretched and knotted it halfway up her breasts. She turned the sari she was wearing inside out and arranged the border to show off her back. Then she stepped out of her shanty, trying to walk mincingly on her toes. She got herself some paan and betel nut on credit after a lot of pleading. But her fingers would not move quickly enough to fold it. Nor did she feel like eating it. She forced herself, only because she had to make her lips red. But her lips would not take the colour and her face would not glow. Her body had no energy. Her walk had no spring. Her heart was despondent. Inside her, sorrow simmered. She tried hard to lessen it, but it only grew. She had lost her mind with the telegram and nothing would bring it back.

Although grief had torn her to pieces, she still walked to the garden and stationed herself there. She had been coming here for many years to do business. So far, nobody she knew had turned up. She continued to chew paan to bring colour to her lips, but her mouth was dry. She kept going to the garden tap to wash her face, to see if she could rid it of its sadness. But the sadness would not go. Men paid no attention to her and the tears in her heart did not have permission to spill.

She smiled at men. She tried hard to muster all the art in her body to arouse them, but none of them approached her. Nobody asked her her price. Time and men passed her by. They felt no concern for her grief. It seemed to her that the day had turned into a dungeon in which all men were locked up.

These are excerpts from River of Flesh and Other Stories edited by Ruchira Gupta and published by Speaking Tiger. Republished here with permission from the publisher.

Ruchira Gupta is a writer, feminist campaigner, professor at New York University and founder of the anti-sex-trafficking organisation, Apne Aap Women Worldwide. She has helped more than twenty thousand girls and women in India exit prostitution systems. She has also edited As If Women Matter, an anthology of Gloria Steinem’s essays, and written manuals on human trafficking for the UN Office for Drugs and Crime.

Baburao Bagul was a radical dalit thinker, poet and writer from Maharashtra, whose writing was among the first wave of modern dalit voices. His first collection of stories, Jewhan Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (The Time I Concealed My Caste) shook up Marathi literature’s ideas at the time with its raw description of the lives of the marginalised and oppressed.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.