Beyond PMAY-U Blueprint: Challenges Facing India's Landless Poor

Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi

“If the poor have to pay out of their own pockets to access government welfare schemes, then the government is failing in its responsibilities,” said a beneficiary of PMAY-U at Jailorwala Bagh Jhuggi Jhopadi (JJ), in Delhi.

Launched in 2015, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna-Urban (PMAY-U) aims to provide affordable housing to India's urban population. The scheme has focused on delivering all-weather pucca houses equipped with essential amenities to eligible households.

PMAY-U is implemented through four sub-schemes: In-Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR), Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS), Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), and Beneficiary-led Construction (BLC).

In the Union Budget 2024, the government has announced an investment of ₹10 lakh crore for the flagship Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) scheme. This includes Central assistance of ₹2.2 lakh crore over the next five years, reinforcing the government's commitment to affordable housing. For all projects under PMAY till 2022, the investment announced by the government was of ₹8.31 lakh crore. This investment, however, underscored a crucial aspect: the Central government's share remains relatively modest compared to the overall investment.

The parliamentary report of 2022-23 provides insights into the funding mechanism of PMAY as:

-

Total Investment: ₹8.31 lakh crore

-

Central government's share: ₹2.03 lakh crore (24.4%)

-

State government's share: ₹1.33 lakh crore (16%)

-

Beneficiary's share: ₹4.95 lakh crore (59.6%)

This breakdown highlights that the central government's contribution constituted only 24% of the total ₹8.31 lakh crore investment, emphasising a significant reliance on state contributions and beneficiaries.

With the new announcement of a ₹10 lakh crore investment over the next five years, Central assistance of ₹2.2 lakh crore suggests that the Central government's share might increase slightly but will remain lower than that of the beneficiaries. This indicates a consistent strategy where the bulk of the funding responsibility is distributed among state governments and largely borne by the beneficiaries.

Reflecting this burden, another resident of Jailorwala Bagh JJ, Okaram Prajapati, told this writer: “We know the struggle of arranging money for the flat. We had to borrow from the open market, family members, and employers at high rates of interest.”

Addressing the Housing Gap

According to Census 2011 data, the total number of slum households stands at 139.20 lakh, with a migrant population of 44.66 lakh. Combined, the housing need for all states and Union Territories, as per the 2011 Census data, is 183.86 lakh. Given the absence of a Census since 2011, it is likely that this number has significantly increased.

In the Parliamentary report of 2022-23, the Ministry concerned stated that 122.69 lakh houses had been sanctioned, 105.32 lakh had begun construction, and 64.33 lakh had been completed. Today, the PMAY website shows updated numbers: 118.64 lakh houses sanctioned (a decrease of 3.3%), 114.33 lakh under construction (an increase of 8.6%), and 86.04 lakh completed (a significant increase of 33.8%).

Despite the government's commitment to completing all sanctioned houses by the end of 2024, the number of sanctioned houses has slightly decreased. However, there has been substantial progress in the number of houses grounded for construction and completed, indicating a strong push towards meeting the existing housing targets.

This data illustrates the ongoing efforts and progress under the PMAY scheme to address the substantial housing needs identified in the 2011 Census. However, despite significant advancements, there remains a considerable gap to meet the total housing demand of 183.86 lakh households.

Houses for the Landless Poor

Residents of Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi.

The majority of PMAY projects have been sanctioned under the Beneficiary-Led Construction (BLC) scheme, which accounts for 60% of the total. States find it more convenient to provide houses in smaller cities to people under the BLC scheme, as they already own land.

In stark contrast, schemes aimed at assisting the landless poor, such as the In-Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR) and Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), account for only 3% and 17% of the total projects, respectively.

Despite the high demand, ISSR has struggled to meet housing needs. As of March 2022, only 4.33 lakh houses were sanctioned under ISSR against a demand of 14.35 lakh houses. This number further dropped to 2.96 lakh sanctioned houses by November 20, 2023. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs cites several challenges for both AHP and ISSR projects, including the scarcity of land within municipal limits, the need for various statutory clearances, and lengthy processes such as tendering, re-tendering, clearing slums for redevelopment, and arranging transit accommodation. Additionally, the unwillingness of slum dwellers to relocate poses a significant challenge for the ISSR scheme.

Case Study: Jailorwala Bagh Slum Redevelopment

Residents of Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi

The Delhi Development Authority (DDA) announced the redevelopment of the Jailorwala Bagh slum in 2012 that was later expanded under the ISSR scheme, with an initial completion target of 2021. Nearly 12 years later, DDA allotted 1,396 flats to the slum dwellers. “We were asked to pay ₹1,76,400 as our contribution for the flat in June 2023.

They said we will get the flat by March 2024, but we still have no completion date,” said Shrikant Prabhakar, a resident of Jailorwala Bagh slum.

Each flat, spanning 340 square feet, features a bedroom, living room, kitchen, separate toilet and bathroom, and a balcony. The entire project's residential area covers around 67,000 square meters, with an extra 1,000 square meters designated for community facilities and parking for 337 vehicles. However, according to a labourer on the site, there is still a lot of work to be done. "We are still working on water pipelines. It will take at least another year to complete," he said.

Rehabilitation Building Next To Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi.

According to residents of the slum, DDA conducted a survey at Jailorwala Bagh in 2015 and again in 2021 to determine eligible slum dwellers for rehabilitation. Approximately, 600 families were deemed ineligible due to inconsistencies in paperwork. Residents pursued the case with the DDA Appellate Authority, and some recently received court orders.

Sumit Kashyap, Residents at Jailorwala Bagh, Ashok Vihar, Delhi.

Sumit Kashyap, a 30-year-old daily wage worker from Jailorwala Bagh, received a court order on May 6, 2024, stating his ineligibility for a flat under ISSR. The order cited his lack of a Voter ID card dating before 2015 or his name in the voter lists of 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015, as a reason for his ineligibility under the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) policy of 2015.

“I have all the other documents mentioned in the policy. I gave them my Aadhaar card from 2011, my bank passbook from 2012, and my ration card from 2014. Even then, I was rejected,” he said.

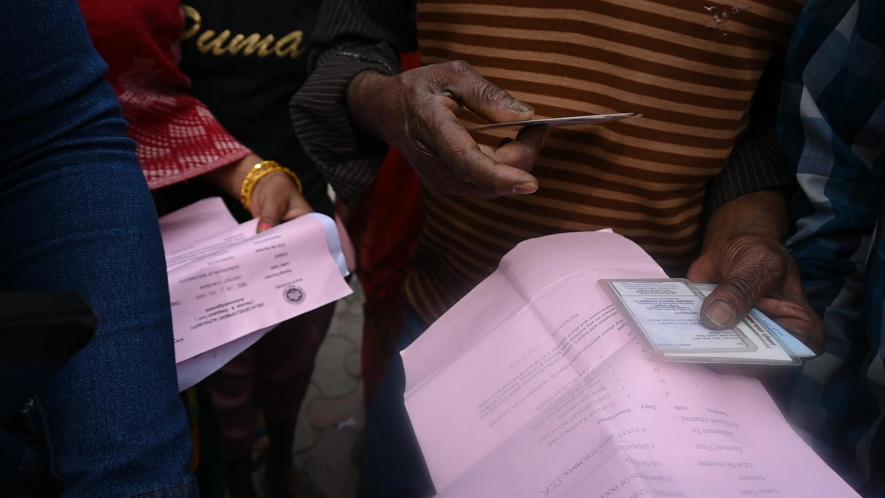

Residents with ID cards for Rehabilitation at Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi.

The DDA order cited Delhi High Court rulings, noting that ration cards and bank passbooks were mistakenly accepted as proof of identity in the DUSIB policy, and stressed the need for a voter ID or inclusion on the voter list. Kashyap expressed his frustration, saying, "Getting any document made in this country is not easy. I tried so hard to get my Voter ID card before 2017, but it was constantly rejected. I finally got it in 2017. I rely on my daily wages—do you think it's possible for me to keep running around for government paperwork all the time?"

Residents with ID cards for Rehabilitation at Jailorwala Bagh Slum, Ashok Vihar, Delhi

In February 2023, the Delhi High Court ruled that slum dwellers cannot be disqualified from rehabilitation merely because their name is not on the electoral rolls. Justice Pratibha M. Singh noted, “The purpose of these policies is to ensure rehabilitation and relocation for economically weaker sections and must be interpreted broadly and beneficially rather than narrowly.”

Many residents, like Kashyap, continue to battle these issues against DDA in the current ISSR project at Jailorwala Bagh.

“We are tired. DDA asked us for money at every step, from filling out forms to submitting documents. They take bribes of ₹300 for every spelling error. Now we have no redressal mechanism left. We were given one hearing, and now I am legally homeless,” alleged Kashyap. This highlights the ongoing struggle of the slum dwellers in Jailorwala Bagh in the PMAY-U, caught in bureaucratic red tape and facing uncertainty despite promises of redevelopment and rehabilitation.

Affordable Housing in Partnership

Under Construction AHP Building at Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh.

The other scheme under PMAY that aims at the landless poor is Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP). The Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP) scheme under PMAY-U provides the highest average financial assistance to Economically Weaker Section (EWS) beneficiaries. However, while Central assistance is fixed for each scheme, state assistance varies significantly, making it a crucial factor in determining the total government aid a beneficiary receives.

For EWS houses constructed under the AHP scheme, states and UTs set an upper ceiling on the sale price of these houses in rupees per square meter of carpet area to ensure affordability for the intended beneficiaries. For example, in Chennai, for each housing unit, the Central government provided ₹1.5 lakh, while the state government contributed ₹7 lakh. The average beneficiary contribution ranged from ₹1 lakh to ₹6.5 lakh.

Under Construction AHP Building at Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh.

Despite the substantial financial assistance, the AHP scheme has not progressed well. Until 2022-23, out of the 20,94,030 houses sanctioned, only 6,70,869 (32%) have been completed. There are also 4,66,548 non-starter houses, which account for 20% of the sanctioned houses. Out of 6.93 lakh completed houses, 5.14 lakh (approximately 74.2%) are still with delivering agencies, and only 1.78 lakh houses have been handed over to beneficiaries.

When asked for state-wise details on why these houses remain with implementing agencies and have not been handed over to beneficiaries, the Ministry explained to the Parliamentary Committee that these houses were unoccupied because the projects were not fully completed. The occupancy of these houses depends on the completion of the entire project, including the availability of water, sewerage, electricity, and other social amenities, along with the issuance of Completion Certificates by the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs).

Under Construction AHP Building at Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

The completion time for houses under the AHP/ISSR schemes typically ranges from 24 to 36 months, which is double the 12 to 18 months required for the Beneficiary-Led Construction (BLC) scheme. This extended timeline further contributes to the challenges faced by the AHP scheme that has barely reached the aspect of beneficiary allotment and is still stuck in its nascent stages.

The PMAY-U scheme, despite its ambitious goals and substantial financial backing, faces significant challenges in execution. While the BLC scheme has seen notable progress due to its convenience for states, the ISSR and AHP schemes struggle with land scarcity, bureaucratic delays, and inconsistencies in beneficiary eligibility.

The case study of Jailorwala Bagh highlights the bureaucratic hurdles and prolonged timelines that plague these projects in the allotment stage, leaving many intended beneficiaries in a state of uncertainty and frustration.

Shubhangi Derhgawen is a freelance journalist based in Delhi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.