A Close Look Into 24-Word Equality Provision in Constitution

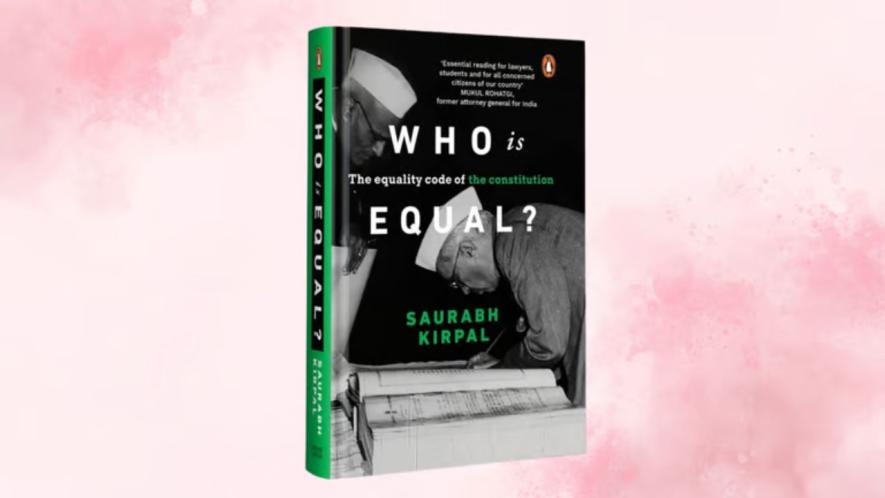

Review of Who is Equal? The Equality Code of the Constitution, Penguin Random House India, Hardbound, pgs. 273, INR 699

There is an African adage: ‘The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.’

Senior advocate Saurabh Kirpal’s Who is Equal: The Equality Code of the Constitution, is an examination of the resonance of this adage within the Indian constitutional framework.

He deftly navigates the judicial interpretation of the 24-word equality provision and probes whether the clause keeps the marginalised insulated from the harshest blizzard of inequality.

In a subtle yet significant departure from the traditional male-dominated language of the law, the author consciously uses feminine pronouns, i.e., ‘she’ and ‘her’, throughout the text. The shift is welcome to make a statement on equality in a manner that challenges the pervasive gender bias and that true equality requires linguistic reforms along with legal reforms.

Kirpal opens his exploration with two fundamental questions: What is equality? Why does it matter? Addressed from a rigorous academic perspective, his work anchors readers in a commitment to the pursuit of equality. He unpacks the rule of law through layered interpretations, revealing how it operates against arbitrary actions, grounded in the reading of the equality clause and rooted in principles of natural justice offering a work that goes beyond abstract wisdom while he discusses philosophers and precedents.

Instead of offering the definitive answer to equality, he attempts to refine the equality clause by sparking a discourse to inquire into the existing interpretation of equality.

Answering the question of the nature of equality, he writes, “One can hardly endeavour to provide the ‘correct’ formulation of equality, particularly when these questions have caused forceful disagreements between the finest minds in the world. The attempt is only to state that the very idea of equality is controversial”, and “this (equality) ideal runs like a golden thread through the entire text of the Constitution”.

The book traces the evolution of equality through India’s long and arduous journey toward independence, beginning with the Commonwealth of India Bill of 1925.

Following the trajectory through the gestation period, its adoption and judicial interpretation, Kirpal writes, “The colonial concept of the master–servant relationship between the State and the citizen was abandoned and a more egalitarian power structure was adopted. Every person was equal in the eyes of the law— a statement that sounds trite today, but was truly revolutionary.”

His usage of the word revolutionary liberally overlooks the contention he raises throughout the book.

The Constitution was not an outright revolutionary draft; at best, it was a radically transformative one designed to forge a new social order amid the enduring tension that continues to ripple through India’s diverse yet stratified society.

Achin Vanaik, in his book Nationalist Dangers, Secular Failings, argues, “The Constitution betrayed its elitist character by placing some principles concerning socio-economic justice in the non-justiciable section of the directive principles, not in the binding fundamental rights.”

In a subtle yet significant departure from the traditional male-dominated language of the law, the author consciously uses feminine pronouns, i.e., ‘she’ and ‘her’, throughout the text.

Dr Ambedkar clarified the meaning of provisions put in the Directive Principles of State Policy as a political roadmap that should be mandated and every political orientation would strive to achieve.

On the dichotomy of the justiciable rights and non-justiciable rights, i.e., social and economic rights, Kirpal writes, “Indeed, given the limited jurisdiction and expertise of the courts, it is likely that most social and economic interventions to make the country a more equal place would happen through a political process.”

Kirpal’s examination of the equality clause extends across critical facets of public and private life, including education, employment, business, democracy and marriage.

For instance, the first constitutional amendment following the landmark State of Madras versus Champakam Dorairajan allowed reservation in educational institutions. In Jawaharlal Nehru’s words, “It is all very well to talk about the equality of law for the millionaire and the beggar but the millionaire has not much incentive to steal a loaf of bread, while the starving beggar has.”

Kirpal further raises critical questions on the exclusion of the creamy layer as addressed in Jarnail Singh versus Lachmi Narain Gupta. He contends that reservations were intended to uplift the entire disadvantaged group contrary to the judicial interpretation focused on individuals.

The fact that reservations were never based on economic criteria, his arguments intersect with the debates surrounding the reservation of the Economically Weaker Section (EWS). Kirpal raises a critical question of whether reservation policies have succeeded in their transformative objective of eradicating graded inequalities. For instance, he refers to disproportionately high dropout rates among disadvantaged groups, compared to those in the ‘general’ category.

Kirpal opens his exploration with two fundamental questions: What is equality? Why does it matter?

Alfred Barton in A World History for the Workers observes, “All classes when they get into power, are convinced that equality is an iridescent dream. All classes but one— the working class.”

In India, the sentiment resonates with around 14.4 crore landless agricultural labourers, representing a vast section of society that seeks equality in its truest, most tangible form, i.e., land reforms.

However, Kirpal’s examination of equality has overlooked this very class. History has proven the fact that backwardness exists because of skewed land relations and its interplay with caste. The Mandal Commission report, in its recommendations, had suggested: “Unless these relations are radically altered through structural changes and progressive land reforms implemented rigorously all over the country, Other Backward Classes [OBCs] will never become truly independent. In view of this, the highest priority should be given to radical land reforms by all the states.”

Similarly, the Bandyopadhyay Commission’s recommendations for radical land reforms in Bihar, a state which has the densest population of landless labourers, remains unimplemented after almost two decades.

This is a pattern too familiar in the political landscape where a concerning gap exists between policy proposal and political will, and where those in power often perceive equality as an ‘iridescent dream’.

In a democracy, true representation of the masses is fundamental, Kirpal’s exploration of equality in a democracy reveals the structural cavity between voting rights and equitable representation.

Even with universal adult franchise being in place, he argues that the representation is far from equal; a vote cast for a losing candidate often disappears into statistical obscurity. He draws a parallel with the 2000 US presidential elections. Al Gore lost to George W. Bush despite winning the popular vote by around half a million votes.

He questions the systems’ capacity to reflect the electorate’s will. Similarly, he draws a parallel with the Indian context where minorities remain underrepresented in the Parliament. He advocates a single transferable vote (STV) for proportional representation of the masses to bring their grievances into public discourse and for them to be treated equally.

The Constitution was not an outright revolutionary draft; at best, it was a radically transformative one designed to forge a new social order.

In strong words, Kirpal contends the fallacy of the centuries-old Hale’s doctrine promulgated in The History of the Pleas of the Crown in 1736, “But the husband cannot be guilty of rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife.”

Kirpal argues that when India was protesting against the 2012 heinous rape in India “almost certainly some woman somewhere in India was being raped by her husband”.

The implied consent, as patriarchal as it can be, remains consistent with penal statutes in India even after the decolonisation of the criminal justice system. To this, he writes, “Whether this is a result of most judges being men and therefore steeped in a patriarchal tradition or whether a result of a genuine conflict of constitutional values is a matter for debate.

“However, with the courts failing to perform their role as agents of social change, there is no doubt that the law of marriage in India remains deeply flawed and skewed against the most vulnerable of its citizens.”

Kirpal, being an openly queer individual, answers the question: ‘Why do queer folks want marriage?’ He argues that marriage is not just an archaic symbol of patriarchy but has more to it. Legally, marriage offers a bouquet of rights that includes tax advantages, adoption rights, succession rights and more— unavailable without formal recognition.

Socially, marriage serves as a marker of acceptance for the marginalised queer community. He ends the book with an adage, ‘An Englishman’s home is his castle. But it seems that the castle only belongs to the man and not the woman with members of sexual minorities being halted at the gates.’

In sum, the book offers an in-depth interpretation of the equality clause that it is not a mathematical formula to be put in a straitjacket. It demands continuous inquiry and interpretation towards a more inclusive and equal society.

As a thumb rule, the legislative intent shall be borne in mind while interpreting the statute Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s speech forewarning about the life of contradictions shall be the cornerstone of interpreting the equality clause.

Kirpal, being an openly queer individual, answers the question: ‘Why do queer folks want marriage?’

In his words, “We are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics, we will have equality and in social and economic life, we will have inequality… Our social and economic structures continue to deny the principles of one man, one value… If we continue to deny it (equality) for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in perils.”

The question remains, how long shall we continue to live a life of pervading contradictions?

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.