Delhi Riots: At GTB Hospital, Fault-lines Blur As Sorrows Mount

The dead have no memory. The living have lost theirs. Or so it would appear after one enters the neuro-emergency ward of the Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, which is overflowing with victims of the communal strife that engulfed North-east Delhi from 24 February onwards.

Lok Mani, a resident of Nand Nagri, is swaddled under a red blanket. His forehead has been covered by a thick bandage. All one can see are a pair of swollen and startled black eyes. He was returning home late in the evening of 24 February after meeting his sister when he was attacked by a stone-pelting crowd that was also armed with knives and iron rods. They left him bleeding and unconscious on the road.

His wife Guddi, along with their 14-year-old handicapped daughter Kiran, are by his bedside. “We do not know who brought him to the hospital except that he was admitted here on the morning of 25 February. When he did not return home the night before, we realised something was seriously amiss and we came looking for him here,” says Guddi.

His aged mother Ganga Devi, who lives alone in Sonia Vihar, has also come to enquire about his well-being. “He is in complete shock and has no memory of what happened to him. We ourselves are so traumatised, we have still to come to terms with this,” says the grief-stricken white-haired woman.

On the next bed lies forty-year-old Talib, a resident of Maujpur. He too was attacked by a mob on the morning of 25 February when he was taking his daughter for her school examination. His head is swaddled in bandages. Heavily sedated, he is in no position to talk. His father Abdul Khalid says, “My son worked in a jeans factory. He was outdoors when a mob attacked him. Fortunately, my granddaughter was not harmed.”

The last bed in the ward has been given to twelve-year old Shafiq who is a resident of New Seemapuri.

Shafiq, in the blue and white night suit all patients are given, looks dazed. His older sister Shireen, a teenager, says, “Imagine—they did not spare a young boy like him. They were attacking people with stones, bricks, bottles and rods. He was beaten with iron rods. He is lucky to be alive.”

The death toll in Delhi’s worst riots in three decades has crossed 42 and left hundreds injured. Shireen, and many others here, are convinced it is the handiwork of “outside elements” brought in to kill, set fires and loot.

Rahul Pal, an eighteen-year old resident of Mahalaxmi Enclave in Karawal Nagar was hit by a stone and was brought to GTB hospital with major head injuries. He was lying unconscious on the road, bleeding heavily. “There were no ambulances or any other transport available. We brought him to the hospital on a motor cycle,” says his father, Raheer Pal Singh.

These disturbing four days have left Raheer Pal all but speechless. “I was a young lad when the Sikh riots of 1984 took place. But what we have seen in the last four days has been worse than hell,” he says.

Rahul opens his swollen eyes, “I am lucky to be alive. A bullet grazed my forehead. I heard it go past. For a moment, I thought I had been hit but luck saved me,” he says.

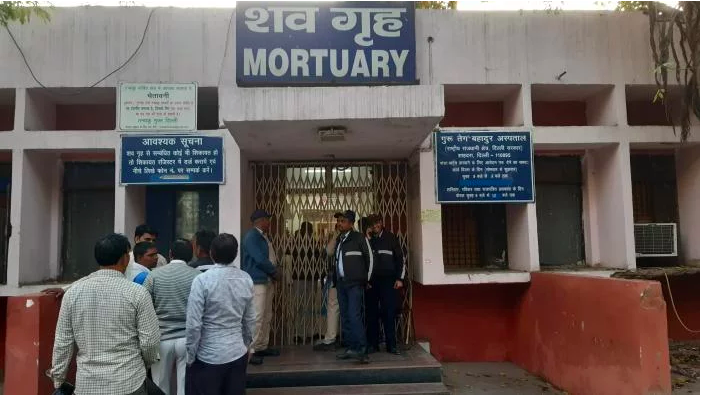

The scene outside the mortuary is frankly depressing. Grief is naturally more palpable here. The loud sobs of grieving families can be heard while others quietly wipe their tears. Some say that Shiv Vihar was the epicentre of the worst carnage. The refrain is also that these attacks were carefully planned, that locals had provided outsiders with details of each mohalla and house. Armed with this information, the arsonists and looters put their stones, bottles, petrol bombs and iron rods to deathly use.

No doubt both Muslim and Hindu victims in this hospital share a thread of pain and sorrow in the aftermath of this riot.

Salim Kesar, an autorickshaw driver and resident of Shiv Vihar, describes the horrors he and his family faced on the night of 25 February. “I looked out of the window and saw a crowd of armed men outside my house, their faces covered as they picked up my parked Nano [car]. They set it on fire. A chill went down my spine. At 10.30 pm, my five children, my wife and I sought refuge in my Hindu neighbour’s house. We stayed with him for the next twelve hours,” he says. “He saved our lives. The next day, he made me wear a saffron kurta, tilak and put threads on my and my children’s wrists and we moved to a safer place.”

Kesar’s brother Anwar, who reared goats and rented out rickshaws for a living, was killed during the riots. It is to collect his body that Salim is in the mortuary.

The Kesars have lived in their home for over 35 years. Salim describes his relations with non-Muslims in the neighbourhood as “excellent”. They knew of late that there were tensions developing between those in favour and those protesting against the amended citizenship law, but he had “never dreamed” that riots would break out.

Mahesh Prasad Tewari, from Bhadohi, is in the mortuary to collect his 32-year old son Aloke’s body. Aloke was killed by a mob while he was on his way home on the evening of 25 February. He lived in Shiv Vihar and used to work in a factory. He has two children, a nine-year-old daughter and four-year-old son. “We have still to break the news of his death to my daughter-in-law Kavita,” said Tewari tears streaming down his bespectacled face.

“I cannot understand why riots are taking place,” says Tewari. “The government has to talk to the protesters. It has to find a solution. In my village, both Hindus and Muslims live in harmony.”

North-east Delhi’s riots have left a trail of death. In this densely-populated urban landscape, neighbourhoods have ended up divided along community lines. In this part of the Capital, temples are situated next to mosques, neighbourhoods of Muslims and Hindus are cheek-by-jowl, and their livelihoods are also intertwined. Today, both communities have members who have progressed economically. However, both the Hindus and the Muslims are at present blaming each other for the recent violence. The absence of any political initiative or attempt to create a semblance of harmony is worsening this divide.

Fareen, who lost her husband Asif, sums up the situation, “Ever since the CAA was implemented, we Muslims have become scared. We want an assurance from the government that even if we do not have documentation, we will not be sent into detention camps. We were born here, have lived here all our lives—where can we go now? But no one is willing to talk to us.”

The medical superintendent of GTB Hospital Sunil Kumar confirms that one woman patient was admitted to the hospital. The hospital has treated around 215 riot victims. Thirty eight victims of the violence have died. Right now, 52 patients are still under treatment.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.