Destruction of the Amazon: What You Need to Know

The Amazon rainforest is a vital carbon sink

Often referred to as the "lungs of the planet" the Amazon is the world's largest tropical forest. Spanning roughly 6.7 million square kilometers (2.6 million square miles), it plays a vital role in reducing levels of air pollution.

When their plants photosynthesize, rainforests absorb massive amounts of carbon dioxide — one of the climate change-inducing greenhouse gasses released into the atmosphere when we burn fossil fuels.

But the Amazon rainforest also influences the water cycle, not only in the counties it spans — Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, French Guiana, Guyana and Suriname — but in other corners of South America too.

Winds from the east bring water that has evaporated from the Atlantic Ocean to the Amazon where it falls as rain. Like giant pumps, the trees soak up the water and release it back into the atmosphere. This way the forest produces about half of its own rainfall.

The Amazon's trees are essential to absorb carbon dioxide and regulate the region's water cycle

But some of the moisture the trees transpire also travels past the Andes to southern and central regions of Brazil and on to Argentina and Paraguay through humid air currents known as "flying rivers." With the climate crisis making some of these areas more susceptible to droughts, the "flying rivers" act as a vital rain source. The Brazilian metropolis Sao Paulo felt this in 2014 when it nearly ran out of water.

"If we lose the water coming from the Amazon, it will push some cities in these areas over the edge," said Philip Fearnside of Brazil’s National Institute for Research in Amazonia (INPA). "It won't be possible to have a city the size of Sao Paulo in that area."

What is the current state of the Amazon rainforest?

About 17% of the rainforest has been cut down already for cattle ranches, soy farms, logging, mines and dams. Much of this destruction is illegal. Last year, about 95% of the areas were deforested without a permit, according to the environmental think tank MapBiomas.

Brazil registered a record high deforestation rate for the first nine months of 2022

Just last month, 1,455 square kilometers were cleared — the largest area ever documented for the month of September. Satellite data from the Brazilian space research agency INPE revealed a record high deforestation rate for the first nine months of the year.

Part of the reason is rampant wildfires. Most are started when farmers burn down trees to clear land for crops and the flames get out of control. INPE detected more than 42,000 fires in September, the highest number since 2010.

"We're very close to a point of no return," said Fearnside, referring to the Amazon’s ability to mitigate climate change. "This could snowball into a disaster and the Amazon is at the center of it."

Touted as a weapon in the fight against climate change, the Amazon has actually become part of the problem — because it is being destroyed. The rainforest is now emitting more carbon dioxide than it is removing from the atmosphere, according to a 2021 study published in Nature.

"I'm going to be honest with you. When I saw our early data, I began to question our method," said Luciana Gatti from INPE who was lead author of the study. "Where was the carbon sink?"

The researchers refined their method and it became clear: Though the Amazon has the ability to absorb billions of tons of carbon dioxide per year, it is now emitting more than that. The southeastern part of the forest, a hotspot for fires and deforestation, is driving this trend.

"They're destroying the Amazon without realizing they are destroying us all," Gatti said of agribusinesses clearing the land.

Land in the Amazon is often cleared for cattle pastures and soy fields

How did we get here?

In Brazil, which is home to more than half the Amazon rainforest, the widespread destruction dates back to the 1970s, when the military dictatorship built a trans-Amazonian highway through largely untouched forest.

The nationalist regime incentivized Brazilians to move there and cultivate land, alleging that foreign companies would otherwise get hold of local resources. People from around the country flocked to the forest to log for timber and raise cattle.

In the following five decades, global demand for beef has grown. Brazil's agribusinesses have boomed, forcing the rainforest to make space for pastures, and later for soy farms to produce protein-rich feed for livestock. About 90% of soy produced ends up in farm animals' troughs. Brazil is one of the world's largest exporters to countries such as China, the Netherlands and Spain.

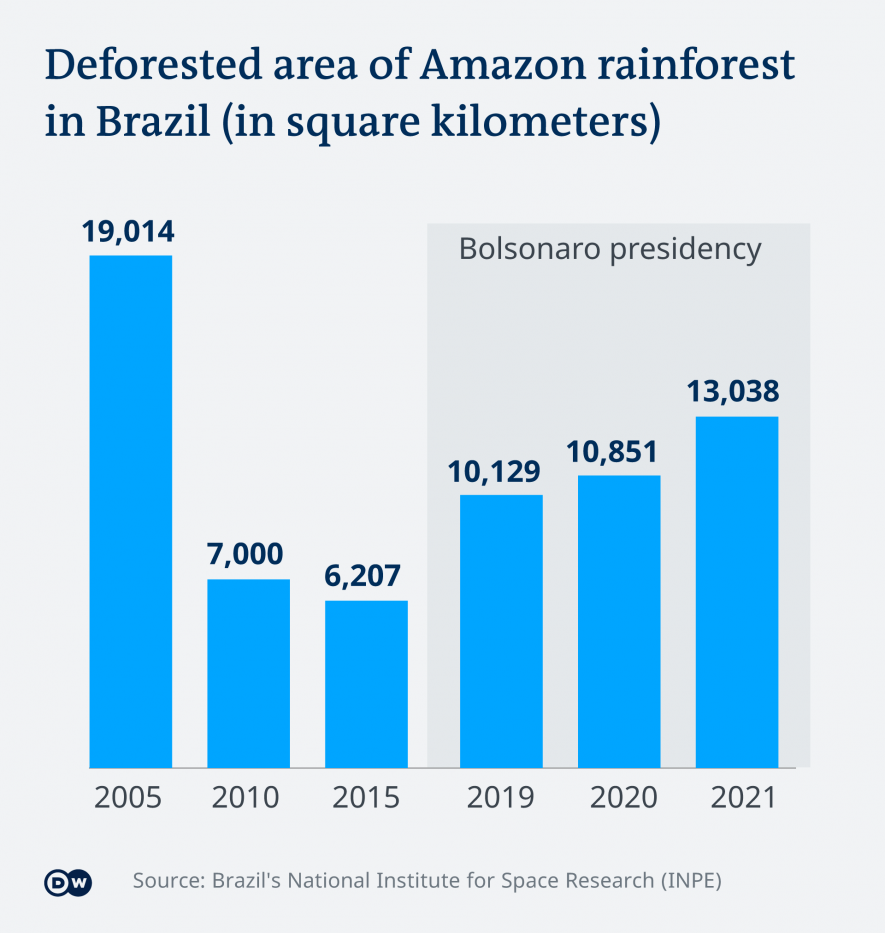

Though deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon took a downturn from 2006 to 2012 due to increased monitoring, they have been soaring since President Jair Bolsonaro came to power in 2019. The far-right leader has cut funding for the environment, downplayed the fires and pushed for Indigenous territories to be opened for mining. Demarcated Indigenous territories tend to have less deforestation exactly because their access is restricted.

How can we protect the Amazon rainforest?

The most urgent solution experts undoubtedly point to is ending deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

There are several ways this can happen. Ramping up monitoring again to crack down on illegal activities, stopping infrastructure projects such as highways and dams from creeping into the untouched parts of the forest, regenerating vegetation in areas that have been cleared. Or pivoting to bio-economies, which aim to make sustainable goods from local resources without depleting them.

"When we talk about climate, we talk about an agenda that is disassociated from biodiversity when in reality they need to be brought together," said Renata Piazzon of Instituto Arapyau, a non-profit promoting sustainable development. "We have the privilege of having the largest tropical rainforest with the biggest biodiversity in the world."

There are several products that grow naturally in the forest, whose production could be scaled up even more: the super berry acai, Brazil nuts, or copaiba, an oil obtained from Copaifera trees.

What is clear is that there is no single approach.

"It will take a lot of knowledge and great effort to save the Amazon,” said Gatti. “But we have to understand that the Amazon doesn't only play a vital role for Brazil or Latin America, but for the entire world. So we have to make that effort."

Edited by: Tamsin Walker

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.