Echoes of Bedanbala: Anti-Prostitution Laws in India

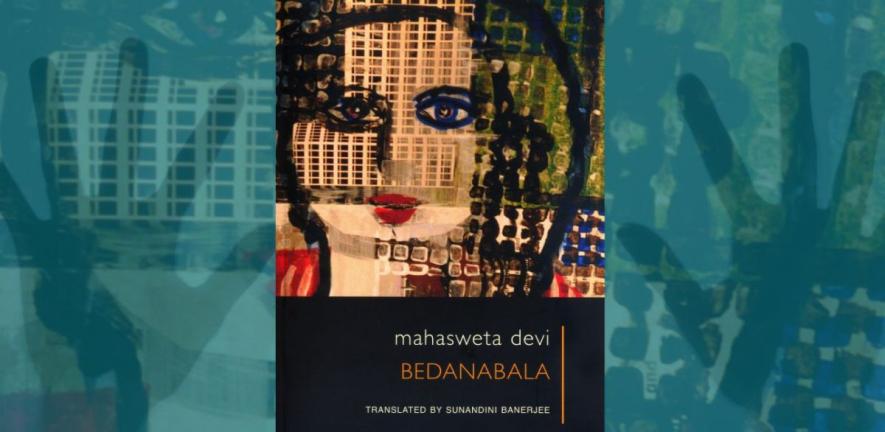

Bedanabala by Mahasweta Devi is a profound exploration of the marginalised and silenced voices in Indian society, specifically focusing on the lives of women who have been ostracised and victimised.

Through her poignant storytelling, Mahasweta Devi brings to life the struggles and resilience of Bedanabala, the protagonist, who represents countless women in similar plight.

The narrative of Bedanabala unfolds against the backdrop of colonial Bengal, a period rife with social inequalities and rigid patriarchal norms. Bedanabala, a devadasi (a woman dedicated to serving in temples, often subjected to sexual exploitation), is at the center of this tale.

Through her poignant storytelling, Mahasweta Devi brings to life the struggles and resilience of Bedanabala, the protagonist, who represents countless women in similar plight.

The devadasi system, historically prevalent in parts of India, involved dedicating young girls to a life of servitude in temples under the guise of religious devotion. These girls were often initiated into the system at a young age, where they were expected to perform various temple duties, including dance and music, ostensibly as acts of worship.

However, the reality was far grimmer; devadasis were frequently exploited sexually by priests, patrons and other influential men. They were denied the possibility of marriage and traditional family life, existing in a liminal space where they were both sacred and stigmatised.

Bedanabala’s journey, from being a vulnerable child sold into this system to a resilient woman fighting against these injustices, highlights the severe oppression and exploitation inherent in the devadasi tradition.

Mahasweta Devi’s writing is evocative and unflinchingly honest. She does not shy away from depicting the harsh realities of Bedanabala’s life, making the reader confront the brutal truths of societal norms and customs that dehumanise women.

The prose is rich with cultural and historical references, providing a deep understanding of the context within which these practices thrived. For instance, Devi refers to the socio-religious sanctioning of the devadasi system, which was often justified by misinterpreting religious texts and traditions.

Ancient texts such as the Natya Shastra and certain Puranas have references to temple dancers and singers, which were later manipulated to sanctify the exploitation of devadasis.

These texts were originally intended to celebrate art and devotion but were twisted to legitimise the practice of dedicating young girls to temple deities, leading to their exploitation by temple authorities and patrons.

Devi also delves into the British colonial period, illustrating how colonial laws and attitudes intersected with and sometimes exacerbated local practices. The author highlights the economic factors that perpetuated the system, such as poverty and the lack of alternative livelihoods for women.

Through Bedanabala’s story, the reader is given a vivid portrayal of the historical and cultural milieu that enabled such practices to persist. Devi’s use of language is both lyrical and raw, capturing the pain, dignity and indomitable spirit of her characters.

One of the most compelling aspects of Bedanabala is its portrayal of female solidarity and resistance. Despite the severe oppression, the women in the story find ways to support and uplift each other. This sense of community and shared struggle is a recurring theme in Devi’s works, emphasising the strength and resilience found in unity.

Bedanabala’s relationships with other women in similar predicaments are depicted with sensitivity and depth, highlighting the emotional and psychological bonds that sustain them.

Bedanabala’s journey, from being a vulnerable child sold into this system to a resilient woman fighting against these injustices, highlights the severe oppression and exploitation inherent in the devadasi tradition.

Mahasweta Devi also critiques the broader societal and institutional structures that perpetuate the exploitation of women. Through her incisive commentary, she exposes the complicity of religious, social and political institutions in maintaining these oppressive systems.

The book is not just a narrative of individual suffering but a scathing indictment of a society that devalues and subjugates women. Devi delves into the hypocrisy of the devadasi system, where religious institutions exploit women while professing spiritual sanctity. This critique extends to contemporary parallels, as the novel prompts readers to consider ongoing issues of gender-based violence and institutional complicity.

The struggles faced by sex workers today resonate with the historical plight of characters like Bedanabala. Many sex workers continue to face exploitation, lack of legal protection and societal stigma. Like Bedanabala, they often navigate a world that marginalises their existence while simultaneously exploiting their labour.

The systemic injustices and the lack of support structures remain critical issues, making Devi’s narrative not only a historical account but also a call to address these persistent inequities.

Bedanabala is a testament to Mahasweta Devi’s commitment to giving voice to the voiceless and her unwavering stand against social injustices. The book is a powerful and moving portrayal of the human spirit’s capacity to endure and resist in the face of overwhelming adversity. It is a must-read for those interested in feminist literature and the socio-cultural history of India.

The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1986

Sex work in India has always been considered taboo. Individuals involved in such activities are deemed outcasts given the ‘unrespectable’ nature of their careers. A well-constructed legislation then becomes pertinent in a country like India where thousands are forcefully dragged into this profession and exploited to a massive extent.

The Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1956 (the ITPA Act) is a legislative framework that deals with trafficking in India. The Act first emerged when Indian became a signatory to the United Nations Convention for the Suppression of Women in Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitations Others in 1950. However, it is limited to commercial sexual exploitation and penalises those who abet or facilitate the same.

Originally enacted as the Suppression of Immoral Traffic in Women and Girls Act, it was later amended in 1978 and again in 1986. Its primary objective is to prevent the exploitation of all individuals including females and children.

However, the ITPA Act has been challenged on various fronts and accused of stigmatising and criminalising sex workers instead of sheltering them.

Mahasweta Devi also critiques the broader societal and institutional structures that perpetuate the exploitation of women.

Especially because, it frequently ignores consent, making it impossible to tell the difference between people who claim they are in sex work voluntarily and those who are being trafficked. As a result, it ultimately denies agency to individuals who are willingly involved in the trade by holding them against their will in protective and rehabilitative facilities.

Section 4 of the Act provides for the punishment of any person above eighteen years of age who knowingly lives on the earnings of prostitution. While the provision intends to target those who financially benefit from the exploitation of sex workers, it disregards the complex socio-economic realities of prostitutes.

There is a lack of caveat for dependents of sex workers, such as their legal heirs or other family members. This perpetuates a cycle of poverty and marginalisation, exacerbating the economic extremes these family members are already being subjected to.

Additionally, Section 17 states that a magistrate, while conducting an inquiry into the offense, if he deems that the person rescued from such an act is in need of protection and care, can detain them for up to three years.

Unfortunately, the concept of ‘protective homes’ is a misnomer as these facilities fail to provide the necessary care and support for sex workers. Allocated resources for basic necessities, including toiletries and food are pitifully low.

Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill, 2021

A revised version of the Bill tabled in 2018, the Trafficking of Persons Bill 2021 seeks to investigate all forms of trafficking including forced labour. But the Bill over-emphasises the criminal response, including the promotion of ‘rescue raids’ by the police and the institutionalisation of victims in the name of rehabilitation, not giving due consideration to their rights and needs, especially in terms of protection.

The Bill grants immunity to trafficking victims for crimes committed under coercion or threat of severe harm, but only for serious crimes punishable by 10 years or more, or death. This means victims cannot claim immunity for minor offences, even if coerced. Additionally, the Bill’s classification of certain trafficking forms as ‘aggravated’ could trivialise other serious offences like sexual exploitation and slavery, leading to potentially less strict prosecution of these crimes.

The Bill continues to deny victims a community-based rehabilitation model and imposes the burden on the accused to prove that the crime was not committed.

The Bill continues to deny victims a community-based rehabilitation model and imposes the burden on the accused to prove that the crime was not committed.

Lastly, Clause 23 of the Bill says that the consent of the victim will be immaterial in the determination of the offence if coercion or receiving of payments was involved. So, even sex workers who are willingly a part of the profession could end up in jail.

Bedanabala’s reminder

Against this background, Bedanabala by Mahasweta Devi sheds light on the enduring struggles and injustices faced by sex workers. The story underscores the flaws in India’s Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, which often ends up punishing rather than protecting sex workers.

To create a fairer society, it is crucial to reform these laws, focusing on the rights and dignity of sex workers and addressing their needs with compassion and understanding.

Acharaj Kaur Tuteja is a fourth-year law student at Gujarat National Law University, Gandhinagar.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.