Explained: Why Has Allahabad HC Struck Down the Madarsa Act?

Image Credit: The Leaflet

IN a significant ruling, the Allahabad High Court has struck down the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004 (Madarsa Act, 2004) enacted by the state government.

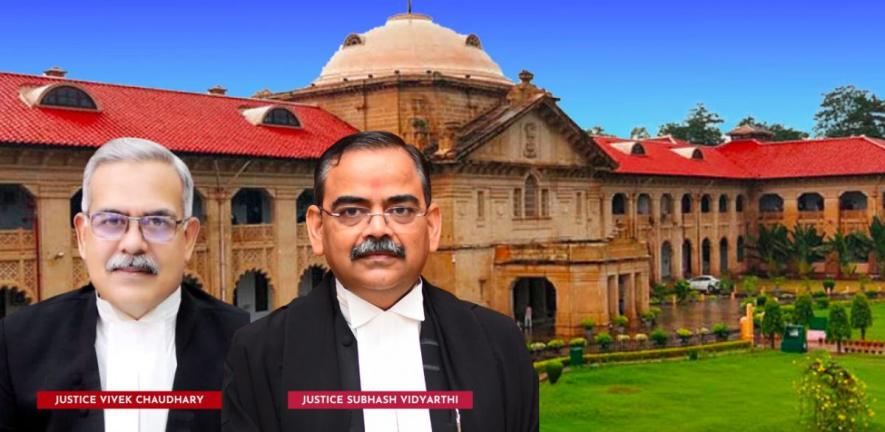

A division Bench of Justices Vivek Chaudhary and Subhash Vidyarthi declared that the State has no power to create a board for religious education or to establish a board for school education only for a particular religion and philosophy associated with it.

The Bench held that the Madarsa Act, 2004 was against the principle of secularism which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India and also violative of Articles 14, 21 and 21-A of the Constitution of India and violative of Section 22 of the University Grants Commission Act (UGC), 1956.

The Bench, however, directed the state government to take steps forthwith for accommodating madarsa students in regular schools recognised under the Primary Education and High School and Intermediate Education boards of Uttar Pradesh.

“The state government for the said purpose shall ensure that as per requirement, a sufficient number of additional seats are created and further if required, a sufficient number of new schools are established.

“The state government shall also ensure that children between the ages of six to 14 years are not left without admission in duly recognised institutions,” the Bench ordered.

Background

On October 23, 2019, a single judge of the high court, while hearing a petition filed by one Mohammed Javed, doubted the validity of the Madrasa Act, 2004.

Javed was appointed as a part-time assistant teacher in 2011 for the primary section of Madarsa Nisarul Uloom Shahzadpur, Akbarpur Post Office, District Ambedkar Nagar on a fixed salary of ₹4,000 per month, subject to 8 percent annual increment.

In his petition, Javed prayed that no regular appointment should be made by the state government, the Madarsa Shiksha Parishad and the district minority welfare officer and his service should be regularised. Further, he prayed that he should be paid a salary equivalent to regular teachers.

In this matter, the judge framed the following question among two other issues: “With a secular Constitution in India, can persons of a particular religion be appointed or nominated in a board for education purposes or should it be persons belonging to any religion, who are exponent in the fields for the purposes of which the board is constituted or such persons should be appointed, without any regard to religion, who are exponent in the field for the purposes of which the board is constituted?”

After framing the issues, the judge referred the matter to a larger Bench. Thereafter, based on the single-judge Order, other petitions were also referred to a larger Bench.

In the meantime, one Anshuman Singh Rathore, who is also an advocate, filed a petition challenging the validity of the Madarsa Act on the ground that the same violates the principle of secularism, which forms a part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India as well Articles 14, 15 and 21-A of the same.

The larger Bench of two judges reframed the issue to the effect: “Whether the provisions of the Madarsa Act stand the test of secularism, which forms a part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India.”

It is in this background the matter was heard by a division Bench.

High court’s findings

The Madarsa Board raised a preliminary objection against the locus standi of the petitioner Anshuman Singh Rathore and also the insufficiency of pleadings to challenge the maintainability of the writ petition.

The high court, however, overruled the preliminary objection stating that no material was placed before it to show that the petitioner Anshuman Singh Rathore, an advocate who is a regular practitioner before the high court, did not have bona fide intentions in filing the writ petition.

The Bench also said that the cause raised by him was a genuine cause, which impacts not only these children and their families but also each and every citizen of the country.

Madarsa Act violates secularism

The Bench, after surveying several judgments on secularism and its concept, opined that in the Indian context, secularism means equal treatment to all religions and religious sects and denominations by the State, without either identifying itself with or favouring any particular religion, religious sect or determination.

On October 23, 2019, a single judge of the high court, while hearing a petition filed by one Mohammed Javed, doubted the validity of the Madrasa Act, 2004.

On this basis, the Bench examined various provisions of the Madarsa Act, 2004.

The definition of “institution” under Section 2(f) of the Madarsa Act includes a madarsa or ‘oriental college’ established and administered by Muslim minorities and recognised by the board for imparting “madarsa-education”.

The definition of ‘madarsa-education’ under Section 2 (h) includes “Islamic studies”.

As far as the composition of the board, sub-Section (3) Clause (a) of the Act requires a Muslim educationist in the field of traditional madarsa-education to be chairman. Under Clause (c), Principal, Government Oriental College, Rampur (a unique college run by the state government having power to give its own certificates of education, with only around 35 students and a principal and no teachers), under Clause (d) and (e) a Sunni Muslim and a Shia Muslim legislator, under Clause (g) one head of institution established and administered by Sunni Muslims and under Clause (h) one head of institution established and administered by Shia Muslims, amongst others, are designated as members of the board.

Section 9 (a) includes, amongst the other functions of the board, prescribing course of instruction, textbooks, other books and instructional material. Section 9 (b) provides that one of the functions of the board is to prescribe the course books, other books and instruction material of courses of Arabic, Urdu and Persian for classes up to High School and Intermediate in accordance with the course determined therefor by the Board of High School and Intermediate Education.

Section 9(c), however, empowers the board to prepare manuscripts of the course books, other books and instruction material referred to in Clause (b) by excluding the matter therein wholly or partially or otherwise and to publish them.

The Bench said under Section 9, the board is not bound to adopt the books of the Board of High School and Intermediate Education as they are but modify the same as it so desires.

Clause (e) and (f) empowers the board to grant degrees, diplomas, certificates or other academic distinctions and to conduct examinations for the same. Clause (g) empowers it to recognise institutions for the purposes of examination.

For the purpose of performing its functions, the board is required to constitute committees and sub-committees under Section 17. These committees are to be constituted from amongst the members of the board itself.

Regulations on the Act were issued in 2016. Under Regulation 2 of Part-I, containing definitions “tahtania” means elementary classes (1 to 5); “fauquania” means upper elementary classes (6 to 8); “quari” means diploma in tajweed-e-Quran; “hafiz” means the certificate of hafiz-e-Quran.

Regulation 3 provides for the qualification of teachers of madarsas. The Bench said, surprisingly, without first recognising institutions, that it recognises certain degrees granted by those private religious institutions, as named in regulation 3(2), as equivalent to senior secondary and undergraduate (alim/fazil) of Madarsa board.

The Bench also looked into the syllabus. It found that the syllabus of primary classes (1 to 8) shows that Quran and Islamiyat, amongst other subjects, are taught in every class.

Similarly in Class 10 (maulvi/munshi), Sunni and Shia theology are compulsory subjects while only one optional subject is required to be taken from amongst math, home science (only for girls), logic and philosophy, social science, science and tib (medical science).

Similarly in Class 12 (alim) both Sunni and Shia theology are compulsory subjects while one of the optional subjects is to be opted from amongst home science (for girls only), general Hindi, logic and philosophy, tib (medical science), social science, science and typing.

The certificates of “hafiz” and ‘“quari” mean certificates of ‘hafiz-e-Quran’ and ‘tajveed-e-Quran’ [Part-I Regulation 2 (l)(m)], which are certificates of having knowledge of the Quran— the religious book of Islam, including its religious instructions, making these certificates only with regard to study of a particular religion and its instructions.

The Bench noted that Sections 2 (a), (f), (h), Section 3, Sections 9 (a), (f) and Part-I Regulation 2 (d), (l) and (m) prescribe for the teaching of a particular religion, its prescriptions and philosophy.

It is on this basis that the Bench said it was clear that under the provisions of the Madarsa Act that to be recognised by the Madarsa Board an institution needed to be set up as a Muslim minority institution and it was also compulsory for a student of a madarsa to study in every class Islam as a religion, including all its prescriptions, instructions and philosophies, to get promoted to next class.

The modern subjects are either absent or are optional and a student can opt to study only one of the optional subjects.

The Bench thus observed that the scheme and purpose of the Madarsa Act was only to promote and provide education on Islam, its prescriptions, instructions and philosophy and to spread the same.

This fact, the Bench said, was admitted to the state government and the board and was also not disputed by any of the respondents or intervenors.

The state government and the Madarsa Board argued that the State has sufficient power to frame laws with regard to education to be provided at the school level, including traditional education. It was argued that in the exercise of its powers under Entry 25 of List III of Schedule VII of the Constitution of India, the State has enacted the Madarsa Act.

It was also argued that if the court finds any provision of the Madarsa Act to be violative of the Constitution of India, it may only strike down such provisions and may save the remaining portions of the Act. The entire Act may not be struck down by the court, the argument went.

Although the Bench accepted that the State has sufficient power to frame laws with regard to education to be provided at the school level, both primary and thereafter up to intermediate level, it said such education has to be secular in nature.

“The State has no power to create a board for religious education or to establish a board for school education only for a particular religion and philosophy associated with it.

“Any such action on the part of the State violates the principles of secularism, which is in the letter and spirit of the Constitution of India. The same also violates Article 14 of the Constitution of India, which provides for equal treatment to every person by the State,” the Bench ruled.

Articles 25, 29 and 30 have no application

The Bench also overruled the argument that the Madarsa Act is in consonance with Articles 25 and 29 of the Constitution. The Bench observed that these Articles relate to the rights of the citizens and not those of the State.

“It is the citizens of this country who have the right to profess and propagate their religion and its values. A citizen of this country doesn’t need to be secular by nature. He can have faith in his own religion or in some/every religion or may not have faith in any religion. But, the State cannot do so. The State has to remain secular. It must respect and treat all religions equally,” the Bench held.

The Bench said that providing education is one of the primary duties of the State, it is thus bound to remain secular while exercising its powers in the said field.

“[The State] cannot provide for the education of a particular religion, its instructions, prescriptions and philosophies or create separate education systems for separate religions. Any such action on the part of the State would be violative of the principles of secularism,” the Bench said.

Regarding Article 30, the Bench said the Article only protects the rights of minorities to establish and administer their educational institutions. The same, like Articles 25 to 29, had no application on the exercise of power by the State government while establishing an education board.

“The protection of Article 30 is only to the minorities, both religious and linguistic, to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

“The board is not an educational institution established and administered by any minority, but is an institution established by the State for providing an education system. It prescribes courses, recognises degrees and certificates, conducts examinations and also recognises schools and colleges for providing education,” the Bench observed.

Eventually, the Bench concluded that the very object and purpose of the Madarsa Act and the relevant provisions are violative of the principles of secularism and thus violate the Constitution of India and cannot stand.

Violation of Articles 21 and 21-A of the Constitution

The Bench observed that the Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasised the need for quality education for the children which is universal in nature.

“Without quality, the idea of education in itself is a failure. Teaching merely one religion and a few languages, without any study of modern subjects, cannot be called quality education,” the Bench said.

Based on the syllabus in the madarsas, the Bench said that education under the Madarsa Act was certainly not equivalent to the education being imparted to the students of other regular educational institutions recognised by the state Primary and High School and Intermediate boards and, therefore, the educations being imparted in madarsas is neither “quality” nor “universal” in nature.

“While the students of all other religions are getting educated in all modern subjects, denial of the same quality by the Madarsa Board amounts to a violation of both Article 21-A as well as Article 21 of the Constitution of India,” the Bench held.

It observed that the State could not hide behind the lame excuse that it is fulfilling its duty by providing traditional education at a nominal fee.

“The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasised on modern education with modern subjects, an education that is universal in nature that prepares a child to make his future bright and to take this country forward.

“It does not prescribe, by any stretch of imagination, limited education with emphasis only upon a particular religion, its instructions and philosophies.

“Education being provided by the Madarsa Board, therefore, is in violation of the standards prescribed by the Supreme Court while interpreting constitutional provisions.

“Therefore this court has no hesitation in holding that the education being provided under the Madarsa Act is violative of Articles 21 and 21A of the Constitution of India,” the Bench said.

Conflict between the UGC Act and the Madarsa Act.

Under the Madarsa Act, the Board is empowered with regard to madarsa education from primary level to postgraduation and research level. The Bench referred to Section 22 of the UGC Act.

Under this Section, a right to confer a degree has been given to a university established or incorporated by or under a Central Act, a provincial Act or a state Act or an institution deemed to be a university under Section 3 or an institution specially empowered by an Act of the Parliament to confer or grant degrees.

The Bench said that the consistent law settled by the Supreme Court is that higher education is a field reserved for the Union of India. Therefore, the state government has no power to legislate in the said field.

Section 9 (a) of the Madarsa Act confers power on the board to prescribe a course of instructions, textbooks, other books and instructional material even for an alim, i.e., undergraduate course; kamil, i.e., postgraduate course; fazil, i.e., junior research programme; and other courses.

Section 9 (e) empowers the Madarsa Board to grant degrees to persons who have pursued a course of study in an institution admitted to the privileges or recognition by the board or even those who have studied privately and have passed an examination of the board.

Section 9(f) of the Madarsa Act empowers the board to conduct examinations of the alim, kamil and fazil courses; Section 9 (g) empowers the Madarsa Board to recognise institutions for the purposes of its examination and Section 9 (h) empowers it to admit candidates to its examination.

Section 9 (p) empowers the Madarsa Board to provide for research or training in any branch of madarsa-education.

The Bench noted that these provisions confer powers on the Madarsa Board which are vested in the University Grants Commission by the UGC Act and fall within the purview of Entry 66 of List I of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution of India and, therefore, the Madarsa Act is violative of the provision contained in Article 246 (1) of the Constitution of India and is unconstitutional to the said extent.

As a result, the Bench declared that the Madarsa Act, 2004 is violative of the principle of secularism, which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India, violative of Articles 14, 21 and 21-A of the Constitution of India and violative of Section 22 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.