Failure of Atlantic Alliance and Neighbours Largely Responsible for Afghanistan Tragedy

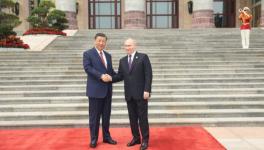

Image Courtesy: Reuters

Dr Radha Kumar is a historian and specialist in ethnic conflict and peace building. She was an interlocutorson Jammu and Kashmir appointed by the Manmohan Singh government and, till recently, director-general of the Delhi Policy Group, an independent think tank. She speaks to Rashme Sehgal about the sudden withdrawal of United States forces from Afghanistan. Kumar calls the latest developments a “horrible tragedy”, caused in large part by the failure of the Atlantic Alliance and Afghanistan’s regional neighbours to work together, and clears some popular misconceptions about India’s role in Afghanistan and the possible fallout of developments. Importantly, she flags the need for a substantive peace process in Jammu and Kashmir, and with Pakistan, to deintensify violence in the region. Edited excerpts.

The Taliban seem to be on the verge of gaining control of Afghanistan, having occupied a large part of the strife-torn country. India has closed its consulates in Herat and Jalalabad and removed its citizens from the consulate in Kandahar. What is this indicative of?

The closure of the consulates indicates a sharp reduction in India’s presence and programs in Afghanistan, from diplomatic to development. It also suggests there might be a corresponding drop in aid. In fact, the Modi administration had already begun to curtail its engagement in Afghanistan from 2014 on—look at the rapid decline in high-level visits between the two governments. It is only recently, after the US announcement of a quick retreat, that the Indian government has stepped up diplomatic activity to acquire some traction with the Taliban. It is too early to see whether efforts will bear fruit, even though it is vital to India’s security that Afghanistan does not become a sanctuary for anti-India armed groups again, as it was under Taliban rule.

Reports suggest that 13 districts in Afghanistan have been taken over by the Taliban in the last 24 hours. They are using captured American weapons and have their eyes on Kabul.

Capturing districts is different from holding on to them after capture. The Afghan army is currently adjusting to US withdrawal, but there will certainly be a fightback. How effective such a fightback will be will depend on several factors: payment, equipment and morale of the troops, the determination of the Afghan government, support from neighbours—all factors in flux at present and therefore difficult to assess.

Bear in mind also that while regional and great powers are all trying to strike deals with the Taliban at present, this semi-hands-off approach by regional and international actors depends on how the Taliban behave and will continue to so depend. If the Taliban gains power but embarks on mass victimisation—of members of previous governments, women, independent media, NGOs—they will face financial and diplomatic pressure, at the least, as will countries supporting the Taliban. If anti-US/Europe/India armed groups do manage to find sanctuary under the Taliban, military pressure, such as airstrikes might be added.

More than 2,00,000 Afghan civilians have been displaced and many more will meet this fate. There is active fighting between Afghan forces and Taliban fighters in 200 of the country’s 375 districts. Hundreds of Afghani security personnel have fled to Iran and Tajikistan. Businesses and professionals are fleeing the country. This does not bode well for the Afghan people. Your comments?

Afghanistan is plunging deeper and deeper into civil war, with all the concomitant evils of refugee and capital flow. It is a horrible tragedy, caused in large part by the failure of the Atlantic Alliance and Afghanistan’s regional neighbours to work together over the past twenty years.

The Indian army helped equip the Afghan army. Why have they failed to build up leadership to take on the Taliban?

Once the US-led NATO missions began, the Indian military was only minimally involved, when at all. Indian military support for the Afghan army was chiefly during the pre-Taliban period, i.e., pre-1996. After that, it was support for the Northern Alliance, which was not really an army. Post-NATO involvement, India continued with its military training programs in which Afghan officers sometimes participated, along with officers from many other countries. These programs are chiefly for different national armies’ officers to learn about each other’s strategic thinking, not about army command or leadership-building.

India has invested in aid to Afghanistan, building hospitals and roads. What will happen to all these assets?

India’s investment and expenditure in institution-building and development in Afghanistan have gradually reduced since 2014. Assets such as schools, hospitals and roads often become primary targets in civil war, and India is in no position to protect them. Earlier, such assets which India built were managed and protected by the Afghan forces and people, now their survival will depend on the different warring forces and their goodwill.

How will this civil war in Afghanistan impact India’s security ramifications, especially in Kashmir?

The violence in Jammu and Kashmir correlates to peace-making by the Indian government. Statistics show that when there has been a substantive peace process in Jammu and Kashmir, and with Pakistan, violence has declined dramatically. Conversely, draconian actions by the government, together with failed hopes for peace-making, can lead to the intensification of violence.

If the Indian government uses the coming year to initiate a peace process along the lines of the [former prime minister Atal Bihari] Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh-led peace processes, then public support for armed groups is likely to sharply decline, which will strengthen our security against Pakistan-backed armed groups. It is unlikely that arms will start flowing out of Afghanistan to these groups just yet since the demand within Afghanistan will be great while the civil war continues, as it is likely to for at least a year and possibly far longer.

Remember, the last time US and Saudi-financed arms were funnelled through Pakistan, whose government diverted supplies to anti-India groups based in Pakistan, and they, in turn, passed them onto militants in Jammu and Kashmir. That situation is unlikely to be repeated this time. Foreign countries that may support one or another side in Afghanistan are unlikely to use Pakistan as a funnel—they will have more direct routes.

India has reportedly held “back-channel” talks with the Taliban. What has been their outcome, given that India had insisted they would not talk to terrorist organisations?

Most countries say they will not talk to terrorists and then do so, so I take such statements with a pinch of salt. As to the back-channel attempts with the Taliban, it is an unfolding story. Judging by the Moscow meeting, there seems to be some cautious progress but we will have to wait and see.

How will this dialogue with the Taliban be interpreted by [the former constituents of] the Northern Alliance?

There is no Northern Alliance. Many of its constituents have been absorbed into the Afghan government and I do not know which way those that were left out will go. Most of them will put the preservation of their fiefdoms first; some may be able to negotiate a deal with the Taliban that will give them some power in their areas, others not.

Will the developments in Afghanistan help Pakistan gain clout? It is under pressure from the US to act against terror, but that does not mean it will listen.

True. But as I have explained, the situation is different insofar as Pakistan will no longer be the funnel for arms to anti-India groups. Pakistani intelligence might be able to recruit Afghan Pushtun fighters for Kashmir again, as they did in 1948 and during the 1980s and 1990s, but I imagine that will take a year or two to do. International pressure on Pakistan is unlikely to increase, as you say.

The Taliban’s aggressive push for a military victory and their refrain from participating in intra-Afghan political dialogue proves that the Doha deal between the US and the Taliban did not provide any framework for peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan. Rather it was like a cover-up to facilitate American withdrawal?

Certainly, the US-Taliban agreement was intended to provide a framework for US withdrawal, and it is equally true that there were no penalties for the Taliban’s repeated violation of the agreement. It can’t be called a cover-up because it was see-through.

With the sudden pull-out, the Americans have pulled the rug from under the feet of the Afghan republic, undoing twenty years of work. Would you say the Afghani people have been thrown to the wolves?

Yes. At the same time, it has to be acknowledged that the US-NATO-Afghan engagement was unwieldy from the start—to avoid any taint of colonial or imperial intentions, the arrangement was to cobble together an Afghan government that was supported by US-NATO military forces. But Afghanistan was intensely fragmented politically, and each Afghan government was formed only after the US intervened. Moreover, each leader depended on US backing more than he did on Afghan public support. That was not a sustainable mechanism—it created a state of constant political and therefore security instability.

Pakistan earlier stated that a Taliban Emirate was unacceptable, but they have back-tracked. Does it mean they played a double game?

No great surprises there. The speeded-up US exit has given Pakistan’s old strategic depth theorists renewed voice. With the endgame nearing, the Pakistani government and military would prefer to keep in with the Taliban rather than lose favour by pressuring them.

Pakistan had provided the Taliban with sanctuaries, training, financial support and weapons. Will the rise of the Taliban and militancy adversely impact Pakistan and its struggling democracy?

The threat of blowback must surely be of concern for the Pakistani government and military, along with a renewed surge of vitality among armed groups such as the LeT and JeM. Pakistani officials often complained about the high cost their country paid for the Afghan war, both in security terms and the cost of hosting refugees. A refugee wave is a more imminent concern than blowback, which will take some time to materialise. Interestingly, there have been relatively few reports of a refugee exodus to Pakistan thus far, in contrast to reports about refugees seeking shelter in Iran and Tajikistan.

Did a perceived “Chinese threat” precipitate US withdrawal?

I think that is a slight misreading. The Biden administration has said that China poses a much greater strategic and security challenge than Afghanistan and that is its focus. Rather than the US withdrawal being precipitated by this challenge, the China challenge replaces the Afghan/terrorism challenge in American public attention. In this sense, it diverts public questioning of the tragedies that have unfolded in the wake of the unilateral US decision to withdraw.

Will China fill the strategic depth provided by the withdrawal of US troops?

That is highly unlikely. China is not seeking to send troops to fill the security vacuum created by the US troops’ withdrawal. Rather it is seeking a deal with the Taliban, firstly to ensure that they do not allow Uighur militants to find sanctuary and training in Afghanistan as they had before 9/11, and secondly to see how they can ensure their Belt and Road Initiative against the fallout of the continuing civil war in Afghanistan.

In any case, Afghanistan does not provide strategic depth for China. If such a role was required to China’s west, it could be filled by the Central Asian Republics, though more as buffers than depth (the latter is Russia’s domain). For China, strategic depth is a goal in the Indo-Pacific.

Victory for the Taliban in Afghanistan will destabilise South Asia and have a global ramification akin to the rise of the Islamic State in Syria and the Levant in 2014. Your comments?

The IS and the Taliban are completely different. Brutal as they were, the Taliban did not have slave ‘comfort’ women, nor were they a peculiarly morphed ideological grouping influenced as much if not more by experience in Europe and the US. There are some IS splinters in Afghanistan; it remains to see how the Taliban will deal with them if or when they establish control over the country.

By and large, the Taliban have been focused on Afghanistan. I do not see them being in a position to expand to any significant extent across the South-Asian or Central Asian region. The threat they pose is that of offering sanctuary to other armed groups, each with their own sectarian or localised regional battle to fight. Since Afghanistan borders six countries (if we include a tiny border with China), the cross-border threat to each is not insignificant, but the threat of all these groups banding together is minimal, at least at present.

(Rashme Sehgal is an independent journalist.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.