Gandhi and Oxford: A Parable for Our Times

Gandhi in the Second Round Table Conference, 1931 (Image from the British Library)

If you look up from the gallery of St. Mary’s Church in Oxford, you will find amongst depictions of mythological animals and heraldic devices, a boss on the ceiling representing Mahatma Gandhi. He sits cross-legged with both hands raised, as if to endow all with benediction, wearing only a white loincloth around his waist and featuring the signature round-framed spectacles, whose glasses are also white — appearing to be opaque. Gandhi’s slender frame in this rather strange depiction is reminiscent of the famous ascetic (or starving) Buddha sculpture renowned in the tradition of Gandhara Art.

Emblem of Gandhi on the Ceiling of St. Mary's Church, Oxford (Image from Oxford and Empire Network)

Gandhi, of course, was likened to a proto-Christian of sorts by liberal Anglicans back in the day. The boss was probably mounted on the roof of the Church at the behest of C.F. Andrews, Gandhi’s friend and an Anglican liberal himself, who identified with the cause of Indian nationalists and taught at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi, and Tagore’s Visva Bharati in Shantiniketan. This was done shortly after Gandhi’s fifth and final visit to Britain, late in 1931. He had come to attend the second of the round-table conferences — a series of unsuccessful peace talks between Indian political representatives and their British counterparts to address the constitutional question of autonomy for India.

Gandhi had been in Britain before, as an anxious and curious student between 1888 and 1891, as an outspoken lawyer agitating to safeguard Indian interests in South Africa in 1906, as a seasoned activist campaigning against racial discrimination in 1909, and as a leader of the Indian Volunteer Corps attempting to contribute to the British war effort in 1914. All these visits were made prior to his permanent return to India and immersion in Congress politics there.

By the time the SS Rajputana arrived at the Tilbury Docks in September 1931, Gandhi had already become a household name in Britain, having remade the Congress organisation in his own image and having imbued Indian politics with a distinct mass-character through his novel techniques of mobilisation and agitation.

Gandhi, who was the sole representative of the Indian National Congress in the conference quickly realised its futility when it became clear to him that there would be no consensus on the question of making an actual political breakthrough. Thereafter, he decided to concentrate his efforts outside the conference as much as possible. In London, he stayed at Kingsley Hall in the East End, spoke with the common people and journalists, addressed students and postal workers, befriended street urchins, and held forth on the contrast between poverty in Britain and in India.

Gandhi travelled widely as well, meeting with clergymen in Chichester, Birmingham and Canterbury and textile workers in Lancashire, got acquainted with Bernard Shaw and Charles Chaplin, and visited university students in Cambridge, Nottingham, Birmingham, LSE, and Oxford. Even though nothing concrete came out of the Round Table Conference, Gandhi emerged triumphant in his public relations, impressing many with his charisma and candid engagement even if they remained unconvinced about his brand of politics.

He visited Oxford twice during this period, staying in the Master’s lodgings at Balliol College, accompanied by his son, Devadas, friend C.F. Andrews, principal secretary Mahadev Desai (later replaced by Pyarelal), and disciple Mirabehn (Madeleine Slade).

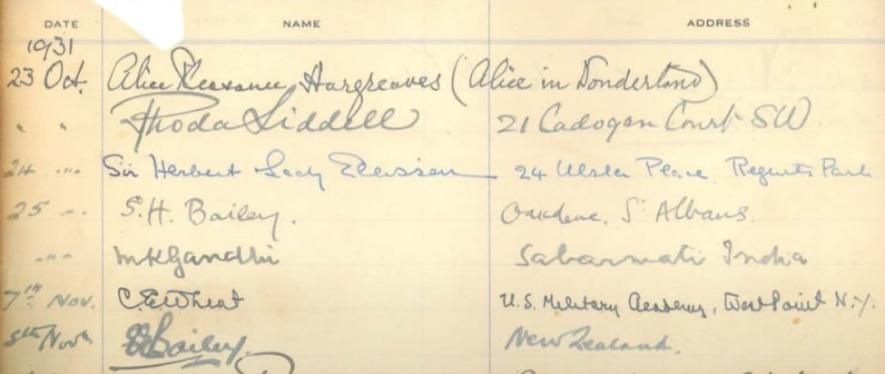

Gandhi's signature in the visitors' book of the then newly inaugurated Rhodes House, Oxford (Image from the Rhodes Trust)

That Oxford wielded disproportionate influence over matters of the British Indian Empire through Viceroys who were its former fellows and civil servants who were its probationary students, was not lost on him. In a large meeting with senior members of the University at the newly inaugurated Rhodes House, he responded to Professors Gilbert Murray and Reginald Coupland’s advice on restraint and gradualism in constitutional affairs by invoking the history of the American Revolution in his own inimitable manner:

“A reformer cannot always afford to wait. If he does not put into force his belief, he is no reformer. Either he is too hasty, or too afraid, or too lazy — who is to advise him, or provide him with a barometer? You can only give yourself, with a disciplined conscience, and then run all risks with the protecting armour of truth and non-violence. A reformer could not do otherwise.”

In Oxford, Gandhi also addressed the students from India and the British Dominions (many of whom were Rhodes Scholars) at meetings organised by the Indian Majlis and the Raleigh Club. At the house of the historian and author Edward Thompson atop Boar’s Hill, he discussed the possibility of a political settlement in which autonomous provincial governments would constitute the stepping stone for an eventually autonomous central government in India with parliamentary undersecretaries like Lord Lothian and Malcolm MacDonald and friends such as Henry Polak and Horace Alexander, but to no avail.

His second visit was much less eventful. Gandhi went to Ruskin College to explain how reading Ruskin’s book, Unto this Last, had influenced him profoundly. On his way back to London, he paid a visit to Colonel Maddock, who had removed his appendix in prison as a government surgeon back in India.

The Master of Balliol, A.D. Lindsay, wrote about Gandhi’s earnestness, throughout his stay, to interact with the most distinguished politicians and academics with the same candour and humility as with ordinary students and members of the public. Throughout his stay in Oxford with Lindsay, Gandhi had impressed him and his wife deeply.

There are at least 30 countries other than India where a street or road is named after Gandhi and at least 70 which can boast of his statues. Gandhi did not visit nearly as many countries in his life. In places, such as in South Africa, his memorials are contested. His politics drew attention and criticism in India and abroad while he lived, and his legacy has been debated vociferously since his demise.

Outside India, he remains one of the most famous Indians of all times. He was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist called Nathuram Godse on January 30, 1948. Today, a Hindu nationalist party is in power in India. Its functionaries and spokespersons have time and again made their allegiances clear in public: Godse over Gandhi. And yet, Gandhi has endured as the pre-eminent international icon of India.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party knows this, as does its supreme leader, Narendra Modi, who spares no opportunity to share in Gandhi’s reflected glory. He repeatedly condones his party and parliamentary colleagues’ remarks which celebrate Godse’s crime and himself pays frequent homage to Godse’s ideological preceptors D.D. Upadhyaya and V.D. Savarkar in domestic politics. However, whenever he goes on a state visit to another country or receives a foreign head of state in India, Gandhi is the name that he invokes. Recently, he led an entourage of leaders from around the world to the Gandhi Memorial at Rajghat during the recently held G20 summit in Delhi.

The contradiction in Modi’s actions is a clever ploy. He is known to weaponise India’s foreign policy objectives and obligations to reap domestic political rewards without hesitation. On the other hand, he projects an image of a secular, tolerant, and peaceful country — Gandhi’s India — in front of the wide world, while Godse’s politics gain wide currency in an India that has never before been so riven by tensions — frothing with deceit and seething with violence and its persistent possibility.

Gandhi’s extraordinary international reputation was not built in a day. It was the outcome of a life lived through relentless honest dialogue with everyone. It cannot be appropriated so easily to create diplomatic alibi for a regime that is insistent on wearing its democratic and non-violent credentials on one sleeve while it goes about wielding the rod, persecuting a fifth of its populace, with the other hand. Gandhi would have had none of it. It might be timely, therefore, to remind ourselves of what he said while addressing students in London and in Oxford in October 1931:

“If India becomes free from this curse of exploitation, under which she has groaned for so many years, it would be up to India to see that there is no further exploitation…Of course you will say that free India can become a menace herself. But let us assume that she will have with herself her doctrine of non-violence, if she achieves her freedom through it, and for all her bitter experience of being a victim to exploitation.”

Sources:

1) Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi vol. 54 (October 13, 1931 – February 8, 1932).

3) Richard Symonds, ‘Gandhi in Oxford’, Oxford Society Journal 48 (May 1996): 82-85.

The writer is a Rhodes Scholar from India, studying Global and Imperial History at the University of Oxford. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.