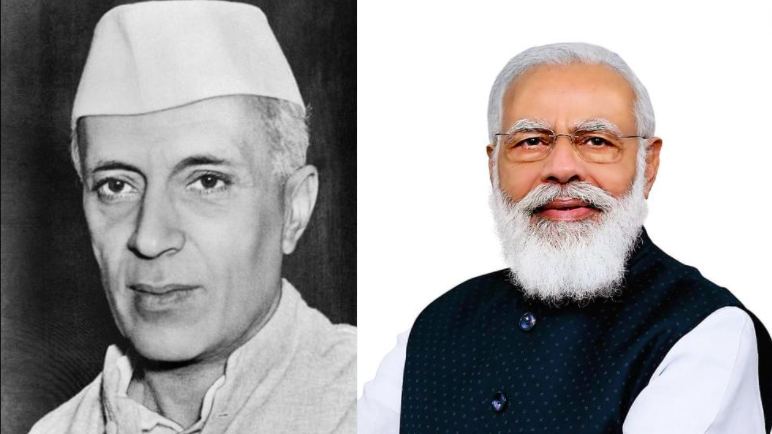

Harmony vs Polarisation: Difference Between Nehru, Modi Poll Campaigns

The significant downward slide in India’s democracy after Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi assumed office in 2014 has been globally calibrated by indices prepared by several respectable institutions.

As the country prepares to celebrate the 75th year of its independence—Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav—it is important to ask if the electoral process has gone backwards to the pre-1947 era as well in spirit, at least, if not in words?

The question arose while pondering over a remark made recently by reputed historian Salil Misra in the course of a conversation with Newsclick. While talking about the first general election in March 1952, he dwelt on how then-PM Jawaharlal Nehru campaigned.

Misra’s observations brought out starkly the contrast between Nehru’s and Modi’s approach to the election and how it underscores the difference in their raison d’être for being in politics. While Nehru was propelled by the idea of applying balm over the trauma of Partition and the ensuing communal riots, Modi is driven by the objective of inflaming passions.

A quick reminder is in order in this post-truth era when claims are made on basis of arguments divorced from facts. After independence, following an inclusive and largely non-violent national movement waged for several decades, the Constituent Assembly agreed on two essential features for the new India. First, India would not be established on the basis of religion and second, there would be universal suffrage. These were the reasons for almost 35 million Muslims staying back in the land of their birth and not migrating to newly formed Pakistan.

Because of the commitment of Indian leaders to establish a secular and democratic State, these Muslims also acquiesced to abolishing their separate electorate, which existed since 1907—although voting rights before 1947 were restricted to the elite. Despite never having a presence in legislatures proportionate to their population, their faith in India was unshaken for a variety of reasons, including being featured prominently as a community in political dialogue.

However, the situation has drastically changed. Now, Muslims are mentioned in political discourse only as a vilified community, an image spearheaded by this regime and led from the front by Modi. There is no one in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to remind its leaders of Raj Dharma.

During the first Lok Sabha election, there was little doubt that the Congress would secure a massive majority—eventually, it won 364 of the 489 seats. Because there was little doubt about his continuation as PM, Nehru used the campaign to achieve two objectives.

First, Nehru strove to develop a baseline agreement or consensus among citizens on India’s basic secular and democratic character. In his speeches, he incessantly spoke more against communalism and its dangers and hardly made promises that could be fulfilled after he was formally elected as PM. He conceded that there would be differences but also drew a boundary within which debates would be conducted democratically.

Another historian Mridula Mukherjee has written that Nehru “converted the (1951-52) election campaign into a referendum on ‘the idea of India’ challenging the communal forces responsible for the Mahatma’s assassination who had been demanding a Hindu Rashtra”.

Second, Nehru enlisted citizens as stakeholders in the process of nation-building. He kept conveying to people that the era of raja and praja (the ruler and the ruled) was over and that leaders would not just do their job but that people would also have to become ‘interested parties’ in India’s future which had to be inherently secular.

Nehru did not provide citizens with a dream of the future. Instead, he said that he was there to enlist the support of all communities to collectively aspire for a glorious future founded on constitutional principles.

The campaign met with considerable success and secured people’s support in overwhelming numbers. This became evident when right-wing communal parties collectively garnered barely six per cent of the popular vote.

In contrast to Nehru’s argument that people should not discriminate on the basis of religious identity, Modi’s regime wins elections by incubating divisiveness and pitting one community against another.

Uttar Pradesh (UP) chief minister (CM) Yogi Adityanath’s assertion that the fight in the recent Assembly elections was a “80 vs 20” contest epitomises the principal thrust of the BJP under Modi and stands in complete contrast to Nehru’s repeated calls for forging a secular country.

Adityanath remained unabashed even after being pinned down on the issue. The CM ‘clarified’ that he did not mention the figures on basis of people’s religious identity but went on to assert that “20% are those people who oppose Ram Janmabhoomi, Kashi Vishwanath Dham and the grand development of Mathura-Vrindavan. The 20% are also those who sympathise with the Mafia and terrorists”. He remained firm on his claim because he did what his ‘boss’ has done in elections since 2002.

In more ways than one, the Adityanath formula, with Modi’s implicit backing, revives the spirit of a separate electorate when Muslims voted for candidates from their community and vice versa for Hindus. This may not have happened with the legislative stamp but has certainly been witnessed effectively.

The BJP’s principal campaign in UP was that the Samajwadi Party was essentially a party of Muslims, Yadavs (read Muslim supporters) and others who supported its ‘minority-appeasing’ politics. The success of this stratagem is evident in the findings of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies’ post-poll survey.

The BJP ploy ensured that Hindus voted only for the party (read party of Hindus) wherever Muslims were significantly ‘visible’: in constituencies where Muslims accounted for 40% or more, 69% of Hindus voted for the BJP. In its goal of consolidating a majority of Hindus in its favour, the BJP has never tried to woo Muslims or reach out to them by even meagre tokenism.

Modi too has campaigned to make people stakeholders, not in nation-building like Nehru, but in pursuing utopian ideas—doubling the farm income, making India a $5 trillion economy, stop being “job-seekers” and instead become “job-givers”.

This regime also revels in using the jargon of ‘outreach’ and “participatory democracy”, but this is a hollow pledge because of its insistence that only its view of issues is acceptable and the ‘right’ one.

The difference between the Nehru and the Modi regimes is that the former built a democracy by consensus while the latter has abandoned the consensual style of politics even within the BJP.

In 1952, Nehru led India into becoming the largest democracy in the world in which the last person in the line had stakes. In contrast, this government is solidifying the country into an authoritarian democracy where citizens are stakeholders in name but are effectively either rubber stamp, ‘invisible’ minorities or those who argue against exclusivist policies and for an inclusive, pluralistic and egalitarian India.

The writer is an NCR-based author and journalist. His latest book is ‘The Demolition and the Verdict: Ayodhya and the Project to Reconfigure India’. His other books include ‘The RSS: Icons of the Indian Right’ and ‘Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times’. He tweets at @NilanjanUdwi

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.