Is History Repeating Itself?

Image courtesy: Vijay Prashad

Over the weekend, an Afriqiyah Airways flight bound from the southwest Libyan town of Sebha bound for Libya’s capital Tripoli was hijacked to Malta. The negotiations with the two hijackers ended in three hours. The men – Subah Mussa and Ahmed Ali – surrendered to the Maltese authorities. When they disembarked from the plane, Mussa held up a small green flag – the symbol of Muammar Qaddafi’s Green Movement. He said that Ali and he had conducted the operation to promote their new party – al-Fateh al-Jadid. The name – the new Fateh – is significant because it echoes the name used in Qaddafi’s Libya for the month of September, when he had conducted his popular coup in 1969.

Since the hijacking was so brief and it seemed of a piece with the anarchy inside Libya, few paid it any heed. The men had used replica weapons and appeared uninterested in violence. They made their political point and left it at that. The Western media suggested that the men had hijacked the plane in order to flee Libya for refugee status in Europe. There is no indication that this was the men’s motive. Their little green flag signified other ambitions.

Sebha, from where the hijacking began, is a junction in Libya’s Sahara. Roads from the northern Libyan cities, where most of the population live, gather here and then branch out towards Algeria and Niger. After the NATO bombing of Libya, the northern rim of the country crumbled into chaos with militia groups controlling territory for brigandage and god. Southern Libya, particularly the Fezzan region, had been a stronghold of Qaddafi supporters, many of whom fled to Algeria and Niger during the NATO war. The two most prominent leaders – General Ali Kana and General Ali Sharif al-Rifi – took shelter in Agadez. When the dust settled, General Ali Kana returned to the Sebha area, where he began to consolidate his support base.

One of the tired clichés of the NATO war of 2011 was that the Libyan people were united in opposition to a very small circle of Qaddafi followers. In other words, a push by NATO’s bombers would liberate Libya and turn it over to the Libyan people. There was no indication here of the wide support base that Qaddafi enjoyed, certainly not the totality of the population but notably important sections of the country. In the Fezzan, where Sebha is the major city, the population had fewer grievances against Qaddafi’s regime. Pockets of pro-Qaddafi support were evident even in the two most rebellious cities – Benghazi and Misrata. But the sheer force of NATO’s support for the uprising meant that only madmen would decide to fight to the end. Qaddafi fighters either slipped out of the country or went deep underground. Those who tried to hide were ferreted out by the victorious militias and either summarily executed or held in prison (there are about 10,000 such people who have been held without trial since 2011).

Qaddafi’s close ally Khuwaildi al-Hamidi, who died in a Cairo hospital in 2015, formed the Libyan Popular National Movement in Egypt. He was eager to run candidates in the elections of 2012 in order to test the strength of the Green Movement, the name given to the pro-Qaddafi camp. But the new dispensation – backed by the West and the Gulf Arabs – banned the movement and disallowed any symbols associated with the Qaddafi era (Laws 37 and 38). Pro-Qaddafi sentiment, in other words, had to fight its politics in the underground. Al-Hamidi and his associates made it clear in 2013 that their objective was not nostalgia. Over the decade before the NATO war, these people had fought against the sale of Libyan land and resources to private capital. This was a battle that brought them directly into conflict with Qaddafi’s son, Saif al-Islam Qaddafi (now free, after years in captivity). Their patriotism, al-Hamidi had said, should be measured in their fealty to the 1969 Revolution and its goals.

Underground politics has its great limitations. Small groups began to re-emerge across the country, including in Sirte (then held by ISIS) and in Derna (previously held by ISIS, but now by ISIS lite). On occasion, these groups would come outdoors and wave their green flags, chanting pro-Qaddafi slogans. Great distress at the capture of the country by militia groups and by rival governments, a country awash with guns and testosterone, has led ordinary people to look back longingly to the Qaddafi era. In 2015, on the fourth anniversary of Qaddafi’s death, the chants from Bani Walid to Benghazi were revelatory – inshallah ashra Saddam, ashra Muammar (May God send ten Saddams, ten Muammars). Slogans such as Muammar is the Love of Millions began to appear on walls. In Sebha, protestors carried their green flags into the streets. When a fighter jet flew low to intimidate them, they fired their guns into the air.

Fezzan, the southwestern region, was not immune to the fissures of tribe and clan that had refracted the rebellion of 2011 and its aftermath. Long-standing animosities between the Tebu and the Tuareg ripped through Fezzan. Around the town of Awbari, towards the Algerian border, the conflict broke into open warfare in 2014. Dueling governments between Tripoli and Tobruk/Bayda inflamed the differences here, where the oil rests beneath the desert sands. The Algerian government hastily closed the border, afraid that the Tuareg would use their regional links to broaden the conflict at about the same time as Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb had begun to strike inside Algeria (after they had been ousted from Mali). A French military base in Niger, not far from Libya, a US military presence in that country and the ubiquitous trans-Saharan smugglers complicates the Tuareg-Tebu conflict even more. In November 2015, representatives of the two sides signed a peace deal, which – apart from some breakdown in January of this year – has held in place.

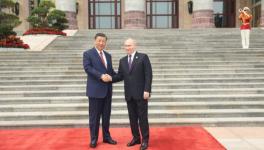

The consolidation of the Green Movement required this peace deal. General Ali Kana’s support base is amongst the Tuareg and the new political party (al-Fateh al-Jadid), which was announced with the hijacking, has roots amongst the Tebu. When Libya’s Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj went to the southwestern town of Ghat – on the border with Algeria – he was greeted with protests from the Green Movement (see picture). This was a week before the hijacking. It suggests much greater confidence amongst the pro-Qaddafi supporters.

A dash across the desert by the Libyan National Army – led by General Khalifa Hafter – brought these troops into Sebha this week. They have, for now, been stopped by Misrata’s Third Force, which had come south to block Hafter’s advance. Hafter, who is backed by Egypt, the UAE and most likely France, has been engaged in a major battle against extremist groups in Benghazi and other parts of eastern Libya. He claims to be the legitimate Libyan army, but refuses to be under the civilian command of either Prime Minister al-Serraj’s weak UN-backed government or its opposition (which is largely based in various political Islamist parties). To complicate matters further yet, Hafter, who was once an asset of the CIA, went to Moscow in late November to seek help in his fight. The realignment of strongmen in search of Russian help to combat terrorism has given Hafter an opening and potentially given Russia its first proxy inside Libya. Rumors suggest that Ali Kana’s southern army is now joined with Haftar and that other pro-Qaddafi forces are considering following suit.

But Tahar Dehech, a close ally of Qaddafi, suggests that the Green Movement has built up its bases and will rise on its own. When asked about an alliance with Haftar, Dehech was clear, ‘Haftar participated in the destruction of Libya in 2011. He is an American. He has his own agenda. The Green soldiers who joined him may have thought of saving Libya by his side, but that will not be the case.’ Dehech says that the Green Movement will prevail in 2017. The men who hijacked the plane to Malta might agree with him. So would the soldiers in Ali Kana’s army. But whether their reappearance will help a Libya torn to shreds by violence is hard to predict.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.