Housing For All by 2022? Here’s The Status

Image Courtesy: pmay-urban.gov.in

One of the favourite promises often repeated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi over the years was that by the 75th year of India’s Independence – that is, by 2022 – all Indians will have houses of their own. Even before coming to power in the 2014 general election he had promised this, and it has been asserted periodically over the years. To achieve this popular goal, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government launched a revamped version of the earlier existing Indira Awas Yojana with more funds and more political backing. It was rebranded as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), with two parts, Gramin (rural) and Urban.

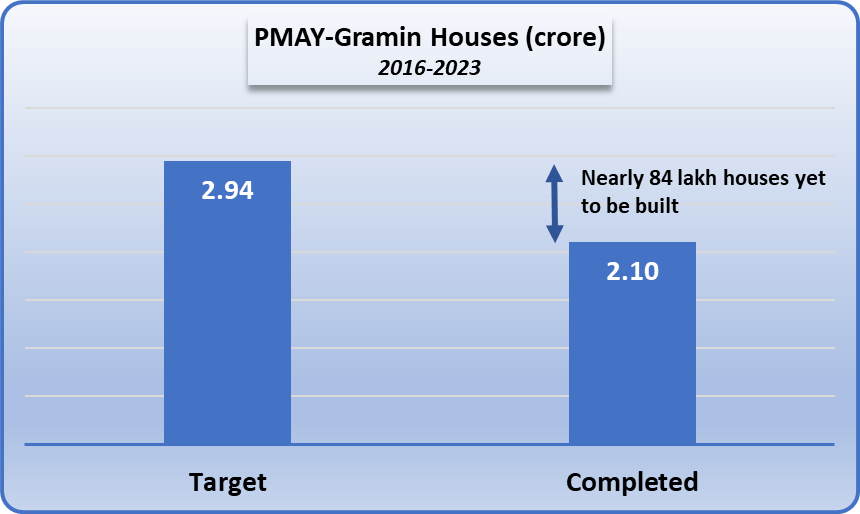

As of January 6, 2023, out of the target of building 2.94 crore houses in rural areas, 2.1 crore have been built, as per the official website for the scheme. That is about 72% of the target – leaving a whopping 84 lakh houses yet to be completed. (See chart below)

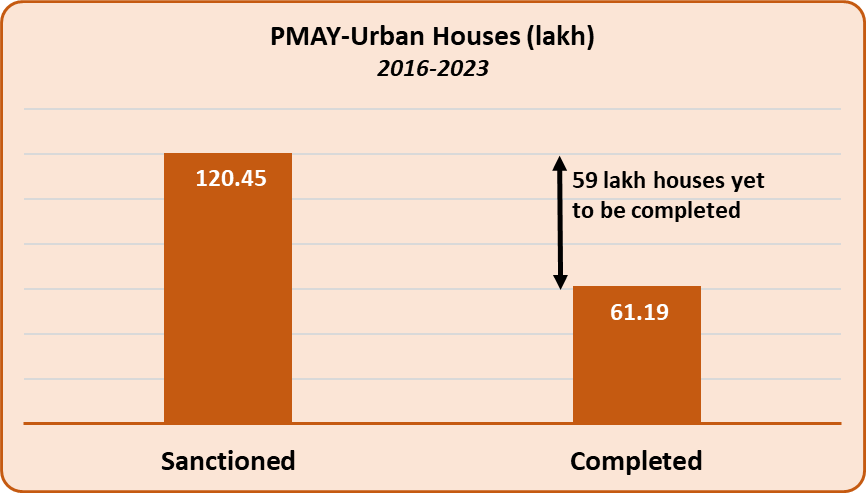

In urban areas, the situation is worse, with about 51% of the target achieved. Out of a sanctioned target of building about 1.25 crore houses, 61.2 lakh houses have actually been completed, according to a government reply in Rajya Sabha on December 12, 2022. That means 59 lakh houses remain to be completed. (See chart below)

Aware that the scheme was running out of time and targets were falling short, the Central government extended its operation to 2024. PMAY-G was extended to March 2024 by a Cabinet decision in December 2021 while PMAY-U was extended to December 2024 in a Cabinet meeting in February 2022. This appears to have put paid to the promise of providing houses to all needy families by 2022.

Managed by the rural development ministry, PMAY-G involves funding of Rs.1.2 lakh for plains areas and Rs.1.3 lakh for hilly areas with labour being contributed by the beneficiary (paid a daily wage of about Rs.90 through the rural job guarantee scheme). Central government and state governments share the expenditure in 60:40 ratio, except for the North-East and hilly areas, where the sharing ratio is 90:10. PMAY-U is managed by the Housing and Urban Affairs Ministry and is differently designed, with four verticals, viz., Beneficiary Led Construction (BLC), Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), In-Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR) and Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS). Private sector construction players are roped in for partnership in this scheme.

Targets Based on 2011 Data

The real shortfall in providing houses for all is larger than reflected in the official figures quoted above because the need for housing has been assessed on the basis of housing deprivation data from the 2011 Socio-Economic & Caste Census. Those who were houseless or living in one or two kutcha-walled or kutcha roofed houses were counted as needing proper liveable houses, and hence to be considered for PMAY-G. The process is routed through the Gram Sabhas, who must verify and recommend names of beneficiaries.

While many people might have, through their own efforts, improved their housing condition since 2011, a large number of new households would also have come up over the years, as population increased. Many households might have descended into poverty too and condition of their houses deteriorated. This equilibrium would have realistically shifted toward more numbers needing better housing. However, the scheme will not be able to take these changes fully into account.

According to a study by Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), urban housing shortage increased by 54%, from 1.88 crore in 2012 to 2.9 crore in 2018.

Besides, there have been innumerable instances of corruption and neglect because the whole decision to include a resident in the waiting list hinges on the village head. The recent exposure of corruption in West Bengal is an example of this sort of discrimination and neglect of the really needy.

Read Also: Corruption Deep-Rooted in West Bengal PMAY-G

In short, the number of needy families that still yearn for a better house to live in is likely to be far more than the shortfall reflected in the official numbers.

Even BJP-ruled ‘Double Engine’ States lagging

Many states have been lagging in implementing the scheme, including even BJP-ruled states. The under-developed North Eastern states, which get 90% of funds from the Central government and are mostly ruled by BJP alliances, seem to be particularly lagging in providing houses, according to latest data available on the official PMAY-G website.

Of the eight North-Eastern states, Sikkim with 78% target achieved and Tripura with 67% achievement are the better performing states. The achievement with respect to targets for the other six N-E states are: Nagaland (21%), Arunachal Pradesh (26.4%), Mizoram (30%), Assam (34%), Manipur (39.4%) and Meghalaya (43%).

Among major states, Telangana is not implementing the scheme at all while Andhra Pradesh was reported to have completed only 18.2% of the target houses while Goa was able to meet only 8%. Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Odisha, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Uttarakhand etc. were all below the all-India average of nearly 72% completion rate.

Some of the states doing well were Bihar, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh (all above 80%), and Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and West Bengal (70-80%). Clearly, implementation is patchy and irregular – and far below the mark.

Read Also: Housing for All: A Basic Need But a Pipe Dream For Majority in Rural India

There has been a tendency on the part of the Central government to imply that the tardy implementation is perhaps due to states’ inefficiency. This does not seem to be the case, as many of the “double engine” governments – with BJP ruling the state – are also lagging.

In reality, many state governments have their own well-functioning state-level schemes, too and these have been providing the houses in parallel. In some states like Kerala, the number of households that needed better houses was very small, at just over 42,212. Out of these over 25,000 houses were built. So, the proportion of target achieved may not account for the ground situation.

The Central push for providing the balance funds amounting to 40% of the total for a particular state also has left state governments in rather dire straits, especially during the pandemic and generally after they have been deprived of revenues due to GST or goods and services tax. Being the implementing agency on the ground, state governments have also had to face land- related disputes, electronic transactions problems and delays in fund transfers.

What all this means is that the much-vaunted efficiency and determination that the Central government often boasts of has not really been effective and workable even in a scheme that has been very popular. This has led to widespread discontent regarding neglect and deprivation.

(Peeyush Sharma contributed in data collation.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.