Long Read | Ronnie Govender: ‘Unbowed, Unbroken’

22 June 2019: Writer and poet Ronnie Govender, who died on 29 April 2021, at the Durban Literary Festival invoking the blessings of Mother Saraspathie, the goddess of learning. (Photograph by Jeeva Rajgopaul)

Ronnie Govender was gargantuan – in appetite and spirit, in his ramrod physical and moral presence, in his creative output, in how he held court as a raconteur, and in those sledgehammer-sized hands with which he grabbed life.

The manner in which he filled a room was matched only by the empathy with which he observed the world around him and drew those who peopled it into an inexhaustible heart: family, friends, kindred spirits, the oppressed, the marginalised and the denigrated.

This, in turn, fed into the work of the award-winning man of letters – a short story writer, playwright, journalist, novelist, poet and activist – who died in Cape Town on 29 April 2021 at the age of 86, after a short struggle with dementia.

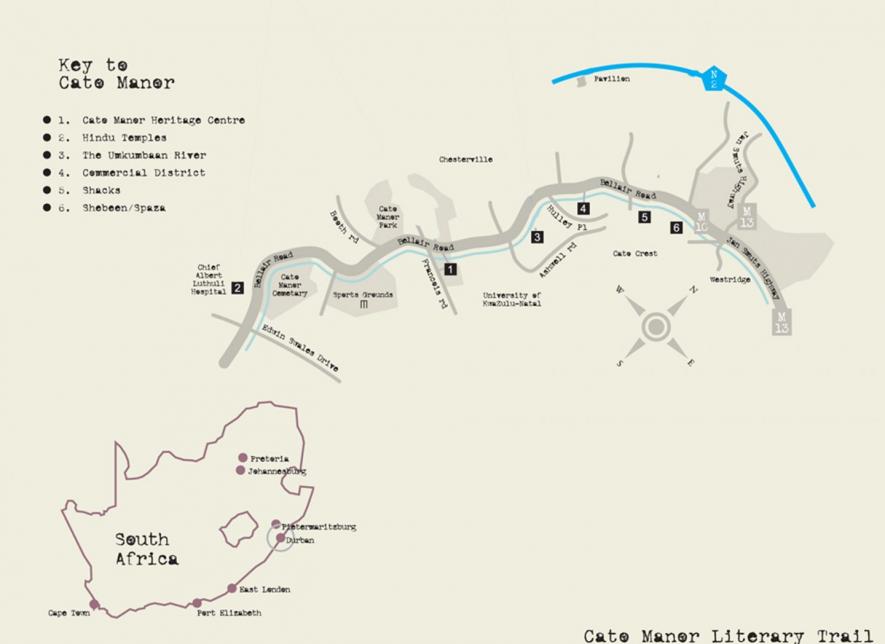

His greatest works drew substance from Cato Manor, where he was born on 16 May 1936, and where he grew up. These include the 1970s play The Lahnee’s Pleasure; the collection of short stories At the Edge and Other Cato Manor Stories (1996), which won the Africa section of the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best First Book; the novel Song of the Atman (2006); and the one-handers At the Edge and 1949.

22 June 2019: Ronnie Govender speaking at the Durban Literary Festival. He says, “It is either ecstasy or deep sadness that propels you to craft the word.” (Photograph by Jeeva Rajgopaul)

At the time, Cato Manor was an area of Durban populated both by the working class of South Asian heritage – which had emerged after obtaining their freedom from indentured labour contracts – and an urbanising African peasantry, drawn to a city promising employment, but which resisted their presence there.

His grandparents, indentured labourers from South India, had settled in Cato Manor, or Umkhumbane, after completing their periods of bondage. The area would evolve into a multicultural and multi-ethnic suburb. It experienced race riots, fanned by the white establishment, in 1949 and was the first to experience forced removals after the passing of the 1950 Group Areas Act.

Cato Manor was, as Govender noted in his poem Who Am I?, filled with the sort of people who made him and of whom he was made: the “cane-cutter, house-wife, mendicant, slave, market gardener, shit-bucket carrier, factory worker, midwife, freedom fighter, trade unionist, builder of schools, of orphanages, poet, writer, nurse”, “the spirit of Cato Manor”.

This was to inform Govender’s own proletarian spirit throughout his life.

A marginalised history

In a 2002 interview with the Sunday Tribune, Govender told Nashen Moodley: “When you write you write about things you are familiar with and you write out of a strong motivational feel. It is either ecstasy or deep sadness that propels you to craft the word. This process has got no boundaries. It might be located within a certain community but at the end you are talking about people. My work is people-centric; you can transcribe that anywhere.

“The history of Cato Manor has been marginalised. It was the first and largest district where more than 180 000 people, most of whom owned their properties, were kicked out.

“Everybody knows about District Six and Sophiatown but nobody knows about Cato Manor. The continued neglect of a wonderful history is morally wrong.”

Forced removals rendered so many people and communities exiles in the country of their birth, often with the inescapable burden of being spectral presences in their own lives.

Govender’s daughter, Pregs, a political activist, former chair of Parliament’s committee on women and deputy chair of the South African Human Rights Commission, and an ANC member of parliament in South Africa’s first democratic legislature, said: “Forced removals were and remain painful for all who go through this. He had a powerful healing weapon: his writing. And his activism. And he used it to heal himself and many others.”

Literary scholar Betty Govinden, whose works include A Time of Memory: Reflections on Recent South African Writings, noted that the project of “remembering” – and what Toni Morrison described as “re-membering” (“where we stitch and patch together our broken past, in order to re-create it”, according to Govinden) – is essential to contemporary South African literature’s response to this traumatised condition. Colonialism, apartheid and dispossession inflict this condition, which is premised on the continuous demand for Black amnesia.

Undated: Map of the Cato Manor literary trail. Ronnie Govender’s writing was profoundly influenced by Cato Manor’s forced removals, which displaced 180 000 people. (Image courtesy of KwaZulu-Natal Literary Tourism)

Remembering and “re-membering” course through Govender’s work, according to Govinden: “In this inescapable and compelling project, we reconstruct past images of places and spaces birthed by the logic of apartheid, but also signifying resistance to it.”

Cato Manor, Govinden asserts, was such a place for Govender and his “peripatetic imagination”, which compelled him to “excavate” and “recreate” from the “archives of his mind”.

Place, people and patois

Pat Pillai, who acted in the first version of At the Edge, which travelled to the Edinburgh Festival in 1991, remembered accompanying Govender on “immersive research” trips to Cato Manor to get the detail of place, people and patois.

In a moving piece published in the Daily Maverick, Pillai remembered drinking (milk in his case) with Govender’s brazos (male friends) from the district who used “Tamil phrases and slang that I’d never heard before” and meeting others whose lingering smiles and comfortable silences spoke of long-time friendships, which Govender’s curiosity and empathy were keen to capture.

“Much of Cato Manor was in ruins or overgrown, but there was enough left for him to point out the hotspots, the streets and the overgrown plot that once held someone’s wood-and-iron home, someone he knew. Zinc shacks were now beginning to pop up. ‘Cato Manor was spontaneous. The beginnings of an integrated community,’ Ronnie said. ‘They [the apartheid government] hated that prospect the most.’ I lifted my pencil and pad. My immersive research process had begun,” Pillai wrote.

“Later, we stopped under the shade of a tree, leaned up against the car and spread our tea and sandwiches on the warm bonnet. In that moment Ronnie Govender wasn’t my director. He was a son of Cato Manor, a disenfranchised South African who was marginalised. I asked about his childhood, his parents, his early days as a young man … his activism for non-racial sport, his days as a journalist, his protest theatre, his family. I listened.

That day I saw a strong six-foot-two-inches man moved as he spoke of community, life, loss and his dreams for a better South Africa. ‘If only those in power saw the potential in all our people 50 years ago, he said. Just imagine! But it’s not too late. We’ll soon have a government by the people. It’s close now.’”

Govinden remembered watching all Govender’s plays with her husband, Herby, and laughing “at the tragedies, the illogicalities, the foibles, the indignities of the apartheid past … Ronnie had an inimitable way of showing up the lunacy and absurdity of apartheid, alongside its unspeakable violence.

“But he also showed how people, constrained to live ‘at the edge’, in the margins, created life-affirming ways of centring themselves,” she said.

“Indeed, he portrayed another kind of living ‘at the edge’. He showed how the oppressed reach deep into ancient rivers of faith coursing through their veins, evoking the song of the atman, the song of the spirit, that remains inviolate.”

Evocative storytelling

Govender often credited his grandmother, Amurthum, for his love of storytelling and an appreciation of his roots. He was fascinated by the Tamil language, which is thousands of years old, and by the Dravidian science and art that spanned the Indus Valley Civilisation and ancient Africa, as evidenced by the archaeological finds in the Karoo and Mpumalanga, which predate the Nguni migration into sub-Saharan Africa and which Govender enthusiastically explored. He also admired Koothu, the epic storytelling folk art incorporating dance and song, which indentured labourers brought to South Africa from 1860 onwards.

This informed Govender’s ability and compulsion “to return to the evocations of ‘primitive’ fireside storytelling”, as he described it, and to his cultural and spiritual roots, as seen in The Lahnee’s Pleasure or the short story Incomplete Human Beings.

In interviews, his memoir In the Manure (2008) and the biography At the Edge: The Writings of Ronnie Govender by Rajendra Chetty, Govender credits his compassion for the downtrodden to his mother, Chellama. From his father, Jack Dorasamy Govender, a bakery delivery-van driver, he would get an early sense of politics. With his father, Govender attended rallies at the Red Square addressed by the likes of president of the South African Indian Congress Monty Naicker, the fiery doctor and activist Kesaveloo Goonam and the ANC’s Albert Luthuli.

Cato Manor, meanwhile, was home to the Natal Indian Congress president George Sewpersadh while the trade unionist RD Naidu, who attended the first Communist International as a South African delegate, was forming the Baking Workers Trade Union around the corner at 44 Trimborne Road.

After his primary education at Cato Manor School, Govender matriculated in 1957 from Sastri College, the only Indian high school for boys in Durban at the time. The principal there, Mr Barnabas, cultivated Govender’s love for writing. This was also nurtured by his elder brother Gonny, a journalist who worked for Drum magazine, the Golden City Post and, in later life, for the BBC in England. One of South Africa’s first Black investigative journalists, Gonny also wrote the book The Martyrdom of Patrice Lumumba.

Writing against and towards

In the 2002 Sunday Tribune interview with Moodley, Govender talked of submitting a short story to that very paper as a 20-year-old.

It was, as Moodley recounted, “about a skinny, bucktoothed, dark boy who, ostracised by his peers, makes friends with a fish in a little pond. The boy feeds the fish every day at the same time until one day he is late and is devastated to find his friend dangling on the end of a rod.”

The editor compared Govender’s work to Ernest Hemingway. “I felt on top of the world but the next thing he told me was that he couldn’t use it because the paper was ‘unfortunately aimed at a white readership’.”

“I went home and I tore that story up. I tore it up. It’s a strange thing – like committing suicide. You punish yourself. I could not explain why I did it, but I did it.” This experience, both petty and commonplace in apartheid South Africa, scarred Govender as much as it fired his already growing disdain for the white establishment. But it would not dissuade Govender from pursuing the word through writing plays and working as a sports columnist for The Graphic, The Leader and New Age newspapers, where he wrote about football and boxing.

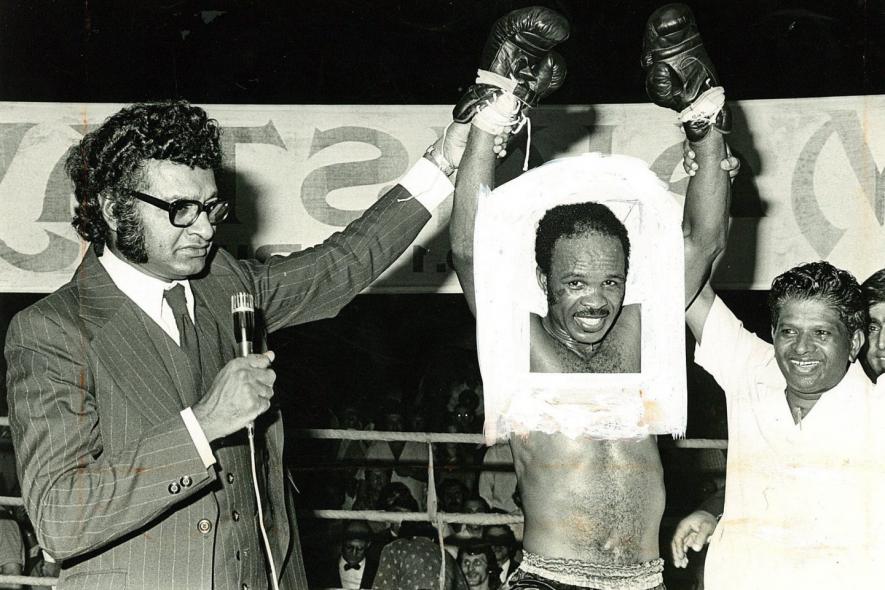

Circa 1971: From left, Ronnie Govender, who wrote a sports column, winner Elijah “Tap Tap” Makhathini and Chin Govender at Curries Fountain. (Photographs courtesy of 1860 Heritage Centre)

The money from New Age financed Govender’s first year at the University of Cape Town. But the paper was soon banned for its alleged communist sympathies, curtailing his studies. Govender returned to Durban to train to become a teacher.

While teaching in places such as Mandeni and Newlands, Govender kept writing. A workshop in the early 1960s with Krishna Shah, whom the Union Artists of Dorkay House had brought to South Africa to direct a local version of his off-Broadway staging of Rabindranath Tagore’s King of the Dark Chamber, led to Govender’s first staged play, Beyond Calvary.

In honour of Krishna Shah, Govender formed the Shah Theatre academy in 1962, which concentrated on the staging of contemporary and indigenous theatre. Govender had, a year earlier, already led a breakaway group that included Bennie Bunsee and Muthal Naidoo, from the Durban Academy of Theatre Arts headed by Devi Bughwan. This was in protest against the Eurocentric approach of Bughwan’s academy, according to his biographer.

As Thavashini Singh notes in her 2009 thesis, Govender was also at the forefront of the cultural boycott in Durban from the 1970s onwards. “Once again artists were caught between their political allegiances and their commitment to their art. Govender, who was clear about his position, refused to showcase his plays abroad and rejected invitations to participate in national festivals. In this sense, theatre certainly was a weapon against oppression.”

The tool of theatre

While not formally trained, Govender pointed to the influences of Bertolt Brecht, Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal, Tagore and Dambudzo Marechera, among others, in his work and methodology. And he revelled in using this organically nurtured intellectual background to take on the academics and theatre critics who populated the white establishment.

In the 1980s, the white supremacist government looked to entrench divide-and-rule politics through the tricameral parliamentary system, which gave “Indians” and “coloureds” limited franchise and representation in separate race-based legislatures.

It did this while clamping down on freedoms by introducing states of emergencies, unleashing death squads to disappear and murder activists, increasing its banning and detention without trial of those it couldn’t kill and censoring the media.

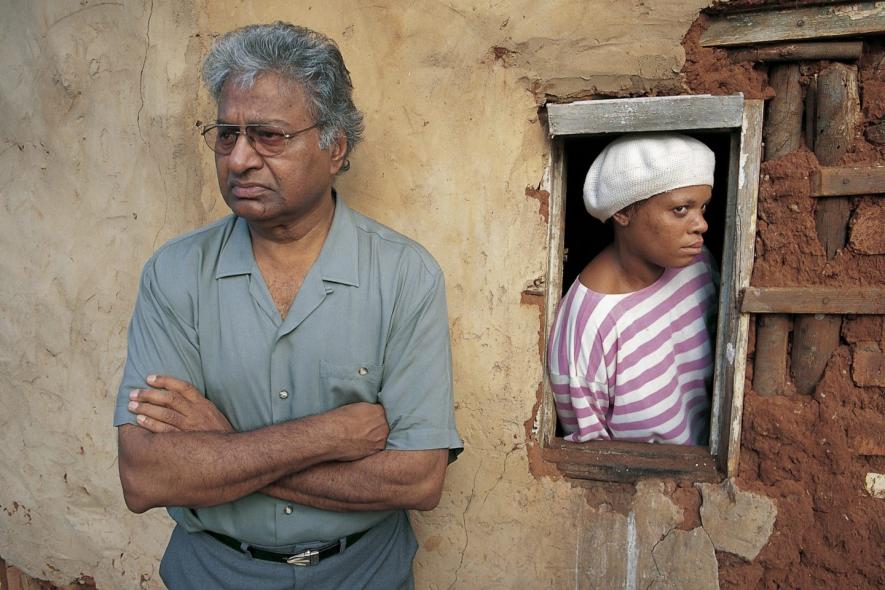

Theatre, and political satire especially, became an increasingly important tool to conscientise and mobilise communities. Govender, in keeping with his independent theatre approach, toured his political plays, such as Offside!, to community halls and school auditoriums around the country.

16 November 2019: Ronnie Govender, Swaminathan Gounden and member of the executive council Ravigasen Pillay at a function to commemorate the arrival of indentured labourers in South Africa. (Photograph courtesy of 1860 Heritage Centre)

Ismail Mahomed, director of the Centre for Creative Arts at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, which previously hosted Govender at various Time of the Writer Festivals, remembers the impact his work had in Johannesburg’s Indian-only suburb of Lenasia, where he grew up: “Lenasia was a political hotbed, but it was culturally conservative. With a mainly Muslim population, it didn’t have the history of theatre and dance which you find in Durban’s mainly Hindu communities. Ronnie’s plays opened our eyes to the power of theatre to conscientise people. It also allowed our parents, who were increasingly fearful for the safety of their increasingly political children, to hide that fear and laugh at the absurdity of life and the system.”

Combined with the mass mobilisation drives by civic associations, trade unions and non-racial sports organisations allied with the United Democratic Front, cultural interventions like Govender’s Offside! contributed to the 4% turnout at the tricameral elections – a resounding grassroots rejection of the apartheid system.

“I am duty bound as a playwright to heighten the social awareness of the people,” Govender observed in 1987.

Govender, in his many guises, had started and run various independent theatres and worked as a rep for South African Breweries by the end of the 1980s.

Myriad lives and layered identities

Into democracy and the 1990s, the former vice president of the Natal branch of the Congress of South African Writers found mainstream work as resident director of the then University of Durban-Westville’s Asoka Theatre, as the marketing manager of the Baxter Theatre in Cape Town and as the director of Durban’s Playhouse Theatre.

He was always a bon vivant with myriad interests, including becoming intensely involved in the anti-apartheid sports struggle as a founding member of the radical non-racial South African Council on Sport in 1973 and an executive member of the South Africa Soccer Federation. He also moonlighted as an announcer at football matches hosted at Curries Fountain, which, in the 1970s and 1980s, was both a sports stadium and a political greenhouse.

Cartoonist Nanda Soobben remembered how his friend would get the crowd geed up with his wit: “He had nicknames for everyone. I remember he would announce Berea’s flying winger James George as James ‘Yathagan’ George. Yathagan was the name of the horse which won the July Handicap that year and the crowd would roar with laughter and cheer his humour.”

Soobben fondly recalled nights of hard drinking, which followed football and boxing matches, and said: “Ronnie could be arrogant, but that arrogance was important to have, especially when you had to stand up for your rights or who you were, when the wit ous [white men] were around and needed to be put in their place – he certainly reaffirmed me as a human and an artist at a time when I was being dismissed as a ‘coolie cartoonist’.”

This view is echoed by Govender’s grandson Karlind Govender who remembered a grandfather who “didn’t like labels. He was never an ‘Indian writer’ but a ‘writer’. We, his grandchildren, never had the opportunity to be just one thing, because he taught us there were layers and layers and layers to all our identities.”

Some of Karlind’s fondest memories of his grandfather include trying to win an argument with him – “I could never tell from his facial expression if I ever did, because he conceded so little” – and being chastised for using his grandfather’s hair gel: “He must have been the only grandfather among my friends who used hair gel,” Karlind said with a laugh.

A working-class intellectual

With a cockerel-like brushback bouffant that remained thick well into his 80s, a strutting bounce, large jaw and the sense he’d always be up for a parah (fight), Govender had something palpably virile and masculine about him: a touch of Norman Mailer, a hint of Hemingway, but also singularly Ronnie Govender. The writer Pravasan Pillay described him as being a “ballie’s’ ballie [an old man’s old man]”.

“Uncle Ronnie was at the intersection of a literary fiction writer and a popular writer. He was a proper working-class intellectual. There was also a very real sense of something hardboiled about him. He was street smart. He had a sharp wit. He was a ballie’s ballie. But he was, of course, also this incredibly sensitive man,” said Pillay, whose collection of short stories, Chatsworth, was recently translated into Swedish.

Govender’s daughter, Pregs, a life-long gender activist, agreed: “Ronnie was both a product of and ahead of his time – one of his first plays when I was very little, Beyond Calvary, was about religion and abortion. It was critical of the narrow moralistic religious view and had a strong female lead. He was a sensitive man who was, also, as you say, a ‘ballie’s ballie’.

11 April 2019: Indentured labour scholar Joy Brain and Ronnie Govender at the Durban Book Fair. (Photograph courtesy of 1860 Heritage Centre)

“My father came from a working-class home where he was very close to a strong mother and had strong independent sisters. He and my strong and spirited mother chose each other as powerful people who were unconventional in many ways,” she added.

Pregs said her own memoir, In Love and Courage: A Story of Insubordination, is replete with stories “about his role in my life and my feminism”.

She described a father who encouraged her to debate ideas and “delighted and nurtured my independent spirit” and indulged a young daughter’s exhortations to break the speed limit. He also sought her advice and input as a teenager examining his work: “I felt proud when he would ask me to read his writing and correct it if I wanted to and when he took my changes seriously. When I criticised the lack of female roles in several plays, he took it on board and created roles that women stepped into.

“When I worked in the trade union movement, he heard from someone that a comrade had physically and verbally attacked me. He went to the union to find the guy, who apparently hid cowering in another office until my father left. So, yes, he was both a gentle father and a man in a man’s world.”

The actor Jailoshni Naidoo, who reprised the over 30 characters in At the Edge in the early 2000s, said Govender had no qualms about casting a woman for the one-hander: “Initially I raised the fact that only men had played the role and his response was typical Ronnie. He said: ‘My darling, my baby’ – this is how he spoke all the time – ‘there is no such thing. I know you can. I believe in you.’”

The show experienced a sold-out run that was extended several times and Naidoo said Govender was a flexible director, open to listening to her perspective on a play that had previously found such success with a male lead.

“But this is unsurprising,” she said, “it is clear that Ronnie was a feminist in how he wrote his characters. The character of Savvy in Saris, Bangles and Bees [a short story], for example, it’s clear that her spirit cannot be contained by the stereotypical role of an Indian housewife, that she sought her own personal liberation.”

A dynamic language

But Govender did not merely seek to achieve social and political liberation. In using patois specific to Durban’s South Africans of Indian descent he liberated a dynamic language.

As he told Chetty: “Yes, I dressed like them and I spoke and wrote in English but I was not ‘English’. When you are born into a language even if it is ‘foreign’, that language becomes you. The challenge was to bridge the nexus between ‘correct English’ and so-called patois. The latter, though born out of imposition, bears the richness of cross-fertilisation, even in servitude. The great strength of English is its elasticity and its dynamism. The problem was that it was appropriated in the cause of colonisation and class. English, however, does not belong to a small tribe on a small island anymore.”

“Ronnie made an important distinction between language and accents,” Chetty said. “We’ve all seen the sadistic delight that white comedians, especially, take in using Indian accents but what Ronnie did was focus on a language that was nimble and dynamic and flexible. A language where the turns of phrase were absolutely dramatic – and he gave it a literary legitimacy.”

This hyperlocal attention to language and space is what won Govender international accolades and standing ovations from Delhi to Edinburgh. Along with the Commonwealth Writers Prize, it also ensured he was recognised for his contribution to English literature with a medal from the English Academy of South Africa in 2000 and the South African government’s Order of Ikhamanga, Gold, for his contributions to democracy, human rights and justice through theatre in 2008.

Yet, it is also what allowed the white establishment in South Africa to dismiss Govender for long periods as a South African Indian writer, rather than a South African writer. This is, Chetty observes, because the white establishment, in media and academia, “have and do exercise their power to devalue your creativity because it is not in the realm of their own imagination”.

Circa 2002: Ronnie Govender was an activist who used political satire in the theatre to conscientise and mobilise communities against the apartheid government. (Photograph by Paul Weinberg/ South)

This racist crisis of the imagination was apparent as recently as a few days after Govender’s death when the Daily Maverick published a tribute to him by Neilesh Bose from the University of Victoria in Canada. It had a headline imposed by the publication referring to Govender as the “grand old man of South African Indian letters”, a distinction that was never made of the white Jewish Nadine Gordimer or of the white Afrikaner JM Coetzee.

I can almost hear Uncle Ronnie, wherever he is, going: “I’m not a fucking ‘South African Indian writer’. I’m just a bloody South African writer.” So it is perhaps apt to include his poem, Who Am I?, as an epilogue.

Who am I?

I have been called

An Indian,

South African Indian,

Indian South African,

Coolie,

Amakula,

Amandiya,

Char ou

Who am I?

I am,

Like my father and my mother and their fathers And their mothers before them,

A cane-cutter, house-wife, mendicant, slave, market gardener, shit-bucket carrier, factory worker, midwife, freedom fighter, trade unionist, builder of schools, of orphanages, poet, writer, nurse

Embraced by the spirit of Cato Manor

Unbowed, unbroken

I am of Africa

Surging with the spirit

Of the Umgeni as it flows from the Drakensberg through the Valley of a Thousand Hills

Of the timeless Karoo clothed in a Myriad fynbos blooms

I am of Africa

Africa pulsing with the spirit

Of Lumumba and Luthuli

Of Rick Turner, of Lenny Naidu,

Of Valliammah, Braam Fischer, Timol and Haffejee of Victoria and Griffiths Mxenge

Whose assassins lurk in the shadows

Their voices still spreading the venom of race hate

Of internecine strife

And who seek to deny me

What is mine, given me

By Thumbi Naidoo, Dadoo, Naicker, Luthuli and Mandela

Given me through the loins of baker’s van-man Dorasamy

Through the womb of house-wife Chellamma

On 16th May 1934

In a humble abode in Cato Manor

They will not displace me

Though I feel the weight of generations I know who I am

I am an African

Update, 14 May 2021: This article has been updated to reflect that Pregs Govender was the chair of Parliament’s committee on women and deputy chair of the SA Human Rights Commission rather than the chair of the Gender Commission as previously stated.

Courtesy: New Frame

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.