Modi’s Autocratic Style Clicks, but is not Fool Proof

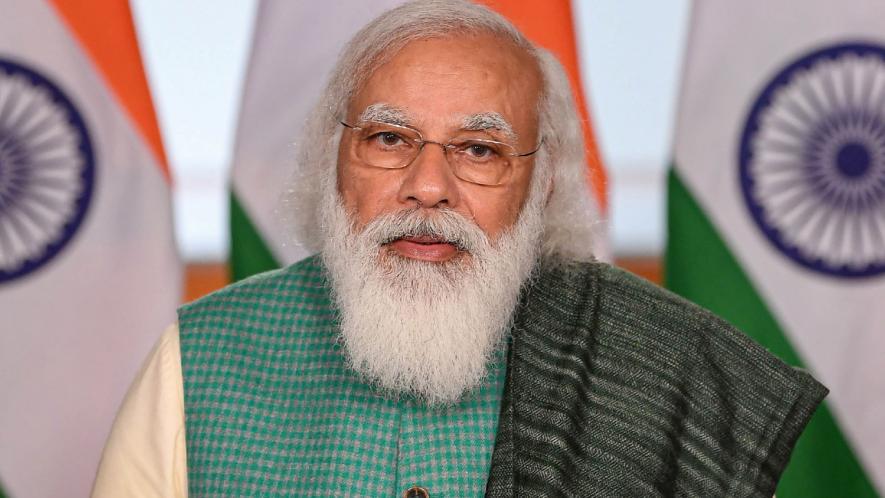

Image Courtesy: PIB/PTI

On 8 November 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the demonetisation of Indian currency notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 denomination in a national telecast with no advance notice. On 24 March 2020, he announced a Covid-19 lockdown in the entire country with four hours’ notice through yet another telecast. Future historians are likely to see both actions of Modi as Tughlaqi farmans or ill-thought, with no prior planning, nor concern for consequences. Both were trumpeted as good for the country but, in reality, proved to be disasters. The more than six years of Modi’s rule are marked with many other similarities to feudal statecraft. Like feudal monarchs punching coins in their name, crores of Covid-19 vaccination certificates issued by the government of India carry his visage as a reminder of his benediction to citizens. His picture on billboards in all petrol pumps announces one or the other social welfare scheme.

While the symbolic form and manner of the Modi regime’s actions may be feudal, their content is autocratic. The imposition of black laws such as UAPA and NSA against those who oppose its policies, its use of police, CBI, and the Enforcement Directorate against political opponents, devaluation of parliamentary procedures, and subversion of the autonomy of the judiciary, election commission, etc., are the most visible authoritarian actions of the Modi government. Democratic forces in India rightly decry the autocratic content and feudal forms of the Modi regime. However, they face a complicated task in challenging them. The Prime Minister is still the most popular leader of the people of India. The Constitution gives citizens the right to choose the bearer of the most powerful office. Yet, they are democratically voting for autocracy as if the grotesquely feudal forms of Modi’s rule do not put off the citizens of a democratic republic.

The way out of this contradiction lies in realising that even though Modi is a democratically elected leader, the source of his appeal does not lie in the democratic politics of the country. The success of his authoritarianism is not just based upon his abilities, the BJP’s electoral management or the RSS’s ideological cohesion. Recent changes like the neo-liberal political-economic order and long-standing anti-democratic tendencies of the Indian state and society provide a breeding ground for the Modi regime to garner popular support despite its anti-people policies and feudal forms of self-promotion.

Ambedkar’s Warnings to the New Republic

Prescient observers of Indian politics have long been aware of the contradiction between democracy and society in India. Dr BR Ambedkar warned about these in many speeches in the Constituent Assembly. In particular, his last speech contained three warnings. One, the preponderance of “bhakti” in Indian politics, which according to him “is a sure road to degradation and eventual dictatorship”. Social and economic inequality in India was the second thing he warned against. While in politics, the Constitution enshrined the principle of one person one vote, the social and economic structures denied the principle of one person one value. His third warning was about the lack of fraternity. He went so far as to claim that “in believing we are a nation, we are cherishing a great delusion”.

What Ambedkar terms “bhakti” in Indian politics is akin to charisma in the Weberian scheme of legitimate authority. Charismatic leadership rests upon the perception of “magical abilities, revelations of heroism and powers of the mind and speech”. The purest types, according to Weber, are “the rule of the prophet, the warrior hero and the great demagogue”. Charismatic leadership is, in principle, non-democratic. The actual content of its authoritarianism, however, depends upon the political context and the intent, and the working style of the leader. Certain actions of Gandhi, for example, his unilateral withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement, and opposition to Subhash Chandra Bose’s candidature for the Congress president, were authoritarian.

That said, the authoritarian edge of Gandhi’s leadership was moderated by his style of working through committees, his habit of explaining his reasons for his actions, and willingness to draw in people from diverse backgrounds without narrow doctrinaire straight jackets, besides the context of a mass movement with clear democratic goals. The public also perceived Indira Gandhi as a fearless warrior-mother. It was because she projected herself as a protector of the poor who took on moneybags and ex-princes and threw an open challenge to the imperialist core in 1971 when the United States sent its Sixth Fleet to the Bay of Bengal to try to save Pakistan from a humiliating defeat. Her charisma had a sharp authoritarian edge due to her summary dismissal of dissent. Still, it lay in tatters when her rule took on a direct authoritarian form during the Emergency, and she was perceived as using state authority for personal gain.

Modi’s charisma is a product of the neo-liberal moral economy. Neo-liberalism is most widely recognised as an economic programme of privatisation and state withdrawal from the economy. As a social ideology, neoliberalism projects the world-view of commodity owners to all spheres of life. The neo-liberal moral economy is the moral dimension of this ideology, which presents self-interest as the sole virtue. At the level of mass psychology, where the devoted followers of a leader like Modi live, neoliberalism has pushed in an unceasing need of “feel good” factors, from consumerist goods and services to extravagant festivities and identitarian practices that provide a feeling of “belonging” to a community.

The kit of “feel-good” goodies in India’s religious context also includes a liberal dose of services and practices that are considered sacred. Due to its hegemonic status rooted in the political-economic form of current capitalism, the sway of neoliberalism spreads much beyond the wealthy and upper strata of society. Its exact form varies with context. Modi appeals to the affluent and privileged savarna caste Hindus who detest even half-hearted steps towards social justice and a much larger, footloose aspirational class that has emerged with expansion of the market in all nooks crannies of the country.

Neoliberalism devalues the notion of a universal good and weakens public rationality. These come in very handy for authoritarian projects that strategically target select minority groups in the name of the interests of the majority. While a weakened public reason is unable to counter emotive identitarian demands of the majority, the oppression of others is not much of a bother to a morality that is centred around self or community interests. Though Hindutva has been around as a political project for more than a century and has enjoyed localised bands of ardent followers among savarna Hindus for generations, attacks on minorities and aggressive glorification of Hindu communitarian identity did not yield political dividend so long as welfarist nationalism dominated the political common sense.

The scenario changed with the neo-liberal turn in the nineties. Modi is the mascot par excellence of Hindutva in the neo-liberal order. What should especially worry democratic forces in India is that Modi’s charisma is more organic and rooted in contemporary India than were of Indira Gandhi and even of Gandhi in their time.

With regard to Ambedkar’s second warning about social and economic inequalities, seven decades of constitutional democracy and capitalism have made fundamental changes. Many oppressed castes have mobilised electorally and laid claim to state office and resources. Colonial underdevelopment has been replaced by a fast-growing market economy. One would have hoped such changes would mitigate inequality-induced threats to Indian democracy. The reality is vastly different. Economic inequality and the disempowerment of working people under neoliberalism is a global phenomenon that needs to be addressed in India, too. Further, democratic forces in India also need to take account of specifically Indian social inequalities, which strengthen the hand of authoritarianism.

Everyday Authoritarianism of a ‘Democratic’ State

Indians enjoy the right to elect the highest office-bearers of the state. The Constitution also guarantees the fundamental rights of citizens. Nevertheless, their interactions with the organs of the state are determined by their rights as citizens. It is especially true of the poor, the members of oppressed castes and minorities. In fact, even better-off Indians from the privileged strata use their social networks or bribe officials when they deal with the Indian state rather than assert their citizenship rights.

The contradiction between the people of India having a say in who will rule over them and their helplessness while facing even lowly state functionaries is a consequence of a historic compromise. The democratic upsurge of the freedom movement forced a change in the legitimacy protocols of the Indian state with a representative form of government. Yet the post-independence state did little to alter the governance practices of the colonial state. The everyday forms of the functioning of the Indian state remain authoritarian.

Violations of constitutional rights do not necessarily affect the legitimacy of those in power. In large measure, this is because the assertion of democratic rights does not rank very high in the moral order of Indian society. Elections to local and national legislative bodies and the market economy have dissolved feudal forms of authority which relied on traditional mores for legitimacy. However, these mores still operate in public life. In particular, caste and kinship-based social networks remain conduits of social control and political mobilisation. Even new avenues of employment are often accessed through these networks. These are the first line of support in times of crisis and the primary arena of socialisation outside the family. These networks affect both individual subjectivity and society, and through these, help weaken the struggle against state authoritarianism. Bonds of mutual obligations through which these networks operate directly constrain the sphere of individual freedom and moral autonomy which underpin citizenship.

On the other hand, these networks also hinder the development of a unitary sense of society. This symbiotic relationship between an organised authoritarian state and fragmented society have created an equilibrium of low expectations and delivery. That is why armies of unemployed migrant workers who walked on national highways for weeks after Modi’s Covid-19 lockdown did not deliver a big enough shock to the system of governance and popular conscience. That is how the state rules, and the poor and the marginal live in India. Neither does the state feel responsible for its actions, nor is a mass upsurge against blatant state coercion a normal reaction of society.

Another pole of uniquely Indian inequality is the cultural capital associated with elite lifestyles, including familiarity with the English language. India has perhaps the most inegalitarian school education system, segregated based on the medium of instruction. It is the only large country that has not developed a higher education system in native languages. Such cultural walls hinder social mobility and have created a culturally segregated “caste” of anglicised Indians who occupy the upper echelons of most professions. Modi’s success presents an outlet to the resentment of the first-generation aspirational class against pre-existing elites. Resentment, of course, is no substitute for self-confidence and creates easy victims of conspiracy theories and fake narratives of grandeur. The cultural machinery of Hindutva is milking this resentment to the hilt.

Breaking the Spell

Every reality is an evolving contradiction. As the BJP’s electoral debacle in West Bengal and Modi’s embarrassing retreat on the three farm laws show, no success is fool-proof. Democratic forces need to capture the contradictory aspects of Indian reality and creatively channel its anti-authoritarian tendencies to strengthen their struggle against the regime. For example, if the self-interest-driven neo-liberal moral order allows Hindutva to tie Indian youth into aggressive communitarian identities, it also frees them from instinctive submission to authority. Democratic sections of this youth are disowning the charms of the vicarious pleasure of violence against minorities and asserting their moral autonomy.

We saw this in the ‘Hum Kaghaz Nahi Dikhaengey’ and ‘Tum Tum Kaun Ho Bey?’ trends in the anti-CAA-NRC-NPR agitation. The challenge before such youth is how to counter fissiparous inclinations of individualism and create organisations that can identify and target everyday authoritarianism of the state in India, including violence on minorities. Grounded youth leaders such as Jignesh Mevani and Kanhaiya Kumar can effectively counter resentments of the aspirational class against cultural elites and channel it to create of an egalitarian society. The class and caste-based domination of the current regime also creates class and caste discontent among its victims. While the kith and community-based networks dissipate victims’ discontent over time through social isolation, the challenge before democratic forces is to build cross-community and cross-caste alliances for mutual support and solidarity.

The success of farmers organisations on this score in Punjab and Western Uttar Pradesh shows that sustained protests against the Modi regime also open up pathways to such solidarity.

As Ambedkar very clearly saw, democracy as a form of government will always be threatened by unequal political economy of capitalism and long-standing authoritarian tendencies of the Indian state and society. The popularity of the Modi regime is based upon the latter—authoritarian tendencies. The challenge for democratic forces is to build a democratic society so that the support mechanisms of authoritarianism, on which leaders like Modi thrive, are automatically disempowered.

The author teaches physics at St Stephen’s College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.