National Rural Health Mission in Shambles, What Does Budget Promise

(NewsClick analysed the status of National Health Mission in India. This is part 1 of a two-part series.)

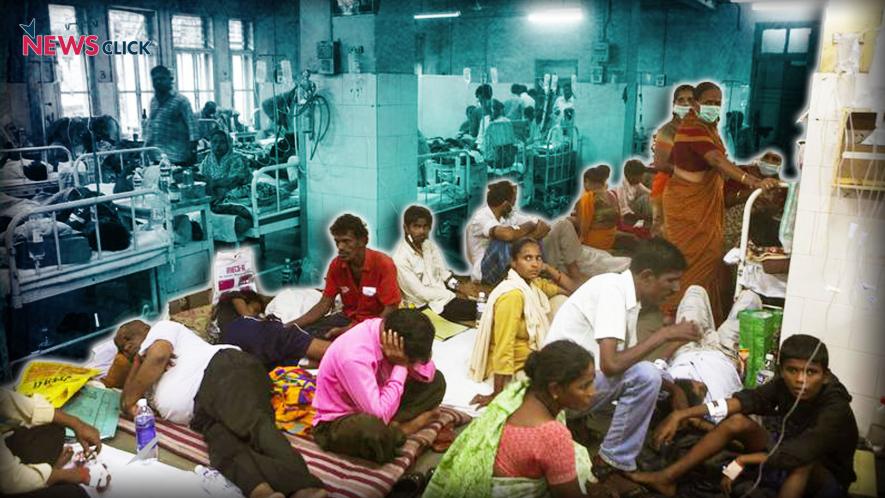

The real thrust of Modi government’s health policy is revealed by the recent Budget details. While health expenditure seems to be increasing, in terms of its share of GDP, it is stagnant. But that is not the whole picture. Even within the stagnating expenditure, the focus is shifting away from primary healthcare delivery through public facilities towards tertiary care through private facilities. This spells a dire threat to the country’s population which is already suffering from rampant disease susceptibilities.

Budget Allocations for Health

Since Financial Year (FY) 2014-2015, the Union Government’s expenditure as a proportion of GDP has been stagnant at around 0.3%. According to the budget estimate for FY 2019-2020, the percentage of the funds allocated to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) is only 2.32% of the total allocation, and only 0.326% of the GDP. According to Oxfam India, the country spends less than neighbouring Sri Lanka and Nepal on health.

In the Union Budget for FY 2019-2020, the allocations for MoHFW was increased by 13.64%, from Rs 56,226 crore in the Budget Estimate for FY 2018-2019 to Rs 64,559.12 crore. The allocation for Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) has gone up from Rs 2,400 crore in the revised budget for FY 2018-2019 to Rs 6,400 crore in the current fiscal year.

Also read: Increase in Budget Allocation for Healthcare Not Enough

Talking to NewsClick, economist Indranil Mukhopadhyay said, “The government, even though there is an increase in funds allocated to the ministry, is cutting down on primary and secondary health care. Tertiary care is important, yes, but it cannot come at the cost of primary healthcare. Insurance-based schemes like PMJAY come at the cost of primary and secondary healthcare.”

National Health Mission

National Health Mission (NHM) is the Indian Government’s largest public health programme. It consists of two sub-missions, National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and National Urban Health Mission (NUHM). The budget allocation for the NHM has been increased by 9.51% in the current fiscal year, from Rs 30,129.61 crore in the budget estimate for FY 2018-2019 to Rs 32,995 crore. However, this allocation does not cater to just NRHM and NUHM. Out of the allocation for NHM, Rs 8,405 crore, that is 25.47% of the funds cater to tertiary care programs, and human resources for health and medical education.

The allocation for NHM as a proportion of total health spending has been continuously declining since 2017. The health and wellness component of the Ayushman Bharat scheme is also routed through NHM, so it further affects the allocation for sub-centres, Primary Health Centres (PHCs), Community Health Centres (CHCs), sub-divisional hospitals, and district hospitals.

According to the Centre for Policy Research, a break-up of the total NHM approved funds along the functional budget heads reveals that a 15% share is going towards community-based healthcare interventions and service delivery initiatives in FY 2018-2019. The share of health facilities meeting the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) out of the total functioning health facilities in the country has continued to decline. As of March 2018, only 7% of the functioning sub-centres, 12% of the PHCs, and 13% of the CHCs met IPHS norms.

According to MoHFW, during the FY 2017-2018, only 62.7% of the funds allocated for NRHM was spent by the department, while NUHM did not spend 11% of the released funds.

Primary Healthcare in Rural India

The Indian public healthcare system was envisaged as a three-tiered structure comprising the primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. The primary and secondary tiers consist of three types of healthcare institutions, namely a sub-centre for a population of 3,000-5,000, a PHC for 20,000 to 30,000 people, and a CHC as referral centre for every four PHCs, covering a population of 80,000 to 1,20,000. The condition of these vital levels that deal directly with the populace is reviewed below.

Sub-Centres

A sub-centre is the most peripheral and first point of contact between the primary healthcare system and the community. The aim of the sub-centres is to provide the minimum healthcare services. As per IPHS norms, each sub-centre should have one female health worker or auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM), and one male health worker.

According to Rural Health Statistics (RHS) 2018, there were 1,58,417 functioning sub-centres across the county as on March 31, 2018. In 2005, this number was at 1,46,026, according to the same data. This means, in 13 years, the number of sub-centres has increased by only 8.5%.

Also read: Unholy Nexus Trumps Public Health

These 1,58,417 sub-centres have a requirement of 3,16,834 health workers in total, and the number of posts sanctioned by the government is 2,81,783. However, according to RHS, there is a shortfall of 65.85% of male health workers, and of 4.54% of female health workers. The amount of vacant posts for male health workers is 41.20%, and for female health workers is 13%. A total of 22.14% of the posts in sub-centres remain vacant.

Meanwhile, in some states like Assam, there is a surplus of female health workers. The sanctioned number of posts for ANMs for Assam is 5,962, while 10,230 workers are in position in the sub-centres. On the other hand, in states like Rajasthan, a large number of posts remain vacant. The sanctioned number of posts for ANMs is 23,859, out of which 5,962 remain vacant.

However, for male health workers, there is a massive shortfall in majority of the states. In Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, the shortfall of male health workers is 92.5% and 96.5%, respectively. In Bihar, there is a shortfall of 87.5%.

Out of the 1,58,417 sub-centres, 7,504 do not have a female health worker or ANM, 75,907 do not have a male health worker, and 5,089 sub-centres do not have either.

Primary Health Centres

PHCs form the cornerstone of rural health services- a first port of call to a qualified doctor of the public sector in rural areas for the sick and for those who directly report or are referred from sub-centres for curative, preventive and promotive healthcare. A typical PHC covers a population of 20,000 in hilly, tribal, or remote areas, and 30,000 populations in plain areas with 6 indoor/observation beds. It acts as a referral unit for 6 sub-centres and refers cases to CHCs and higher order public hospitals located at the sub-district and district level.

Also read: Rajasthan’s Primary Health Centres: A Saga of Insufficient Doctors and Poor Infrastructure

As per IPHS norms, PHCs have a minimum requirement of 11 medical practitioners of various capacities including a doctor, pharmacists, nurses, lab technicians, and male and female health workers and assistants.

Currently, there are 25,743 PHCs functioning across the country, according to RHS 2018. In 2005, this number was 23,236. According to RHS, there has been only a 10.8% increase in the number of PHCs in 13 years.

In the functioning PHCs, there’s a shortfall of 10,557 female health assistants. For male assistants, this number is an even larger 16,981. There’s a shortfall of 3,673 doctors.

Out of the 25,743 PHCs, only 4.47% have four or more doctors. A majority of the PHCs, 57.5%, are functioning with only one doctor, and 5.8% of the PHCs do not have a doctor. Only 28.08% of the PHCs have female doctors present, 34.57% of the PHCs do not have a lab technician, and 15.73% of the PHCs do not have a pharmacist. As many as 15 states reported having zero PHCs running as per IPHS norms.

It is evident that mere lip service is being paid for the maintenance of the lower levels of healthcare delivery system. Lack of infrastructure, lack of health personnel, lack of drugs and lack of support systems like transport have turned it into a mere shell. While the Modi government boasts of initiating the world’s largest health “assurance” scheme – Ayushman Bharat – it has hollowed out the actual system that could have delivered health for all.

Also watch: "Ayushman Bharat Scheme Won’t Cure the Ailing Public Health Sector in India"

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.