New Education Policy 2020: Did it Forget Tribal Students?

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: Social Media

Even after 74 years of Independence, tribal literacy in India has not reached desired levels. The high dropout rate among tribal students—70.9% for classes I to X according to the Statistics on School Education, 2010-11—is a glaring example of the challenges that need to be addressed. India has the single-largest tribal population in the world, constituting 8.6% of the population as per Census 2011, but this is not a homogenous group. Some 574 individual groups make up India’s tribal population. Members of each tribal group tend to follow almost identical occupations, but each is at a different level of social and economic development. Yet on the whole, a considerable proportion of tribal children remain outside the school system. The question is whether the New Education Policy, 2020, can address the central issues associated with tribes and poverty.

Even in the age of globalisation, many countries have succeeded in providing equitable treatment to citizens, but in India tribal communities remain distant from the mainstream and deprived of benefits of growth or development. India’s diversity has made the social fabric highly stratified and hierarchical. Social and economic opportunities are differentially distributed along caste and class lines. There are wide divergences in ecology and geography which, too, relate to occupational differentiations among tribals.

That said, the predominant occupation of three-quarters of Indians is agriculture, and more than 65% of the population lives in rural areas. India’s elitist and discriminatory social order has made the gap between tribals and others in terms of access to opportunities and participation in development wider. Scheduled Tribe groups have traditionally lived in more remote areas, in closer proximity to forests and natural resources, and in regions not well-served by roadways, nor near places of political, financial, industrial or business and entrepreneurial importance. Thus, tribal India is characterised by lack of infrastructure, widespread poverty and indebtedness. The resultant social deprivation tellingly reflects in their educational backwardness.

However, no limitation—geographical or socio-economic—has stopped the forces of modernisation and accumulative processes of production from making massive encroachment into the natural habitats of tribal communities. This has resulted in their displacement, poverty and heightened exploitation through bonded labour. The Indian government has banned child labour from unsafe occupations, but it has found both free education and the ban on child labour difficult to enforce among tribals. That is why the term “double disadvantage” is used to characterise the socio-economic and spatial marginalisation of Scheduled Tribes.

“Why is it so important to close the educational gaps, and to remove the enormous disparities in educational access, inclusion and achievement? One important reason for this is for making the world more secure, as well as fairer. HG Wells was not exaggerating when he said, in his Outline of History: ‘Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.’ If we continue to leave vast sections of the people of the world outside the orbit of education, we make the world not only less just, but also less secure,” Amartya Sen wrote in 2003.

It is a proven fact that students learn better when they are active participants in learning. But coupled with poor infrastructure and low standards of teaching, curricula that neither relates to the lives of tribal students nor teaches them about their history has made many tribal communities disenchanted with the present education system. Further, educational reformers such as John Dewey believed human beings acquire knowledge through a hands-on approach; students must interact with their environment to learn and adapt. Rousseau, in his theory on education, also cited the importance of using expressions which can generate a well-balanced and independently-thinking child.

Problems and education indicators

In most countries, it is compulsory for children to receive at least primary education. The major goals of primary education are basic literacy and numeracy, establishing foundations in science, mathematics, geography, history and other social sciences. In addition, the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations sought to universalise primary education by 2015. However, due to shortage of resources and lack of political will, massive gaps remain. This reflects in high pupil-to-teacher ratios, shortage of infrastructure and poor teacher training.

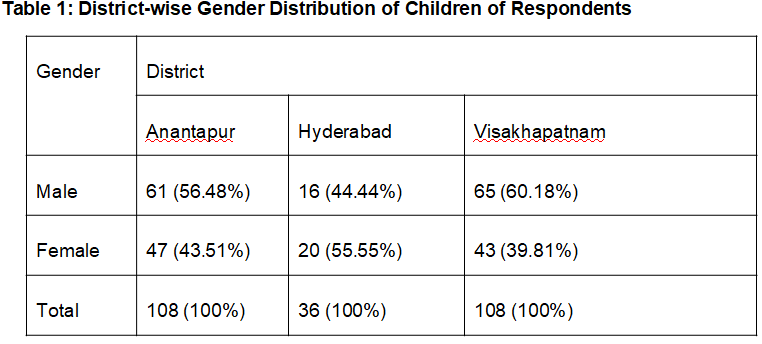

In India, education has been made free for children aged between six and 14 years, or up to class VIII under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009. Due to this, many private-run schools have mushroomed. Against this backdrop, the following section analyses socio-economic aspects related to tribal students, the infrastructure facilities of schools accessed by tribal families, student participation in learning and discrimination faced in schools. The effort is to deal with the perceptions of primary school students on the above aspects. For instance, it is almost a foregone conclusion that the girl child, especially in rural India, is generally discriminated against when it comes to providing education. The underlying justification would be: “How will education be useful for a girl who would later have to perform only domestic tasks?” (See Table 1, based on this author’s field study undertaken between 2012 and 2014).

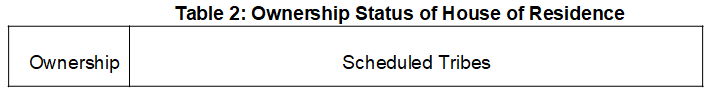

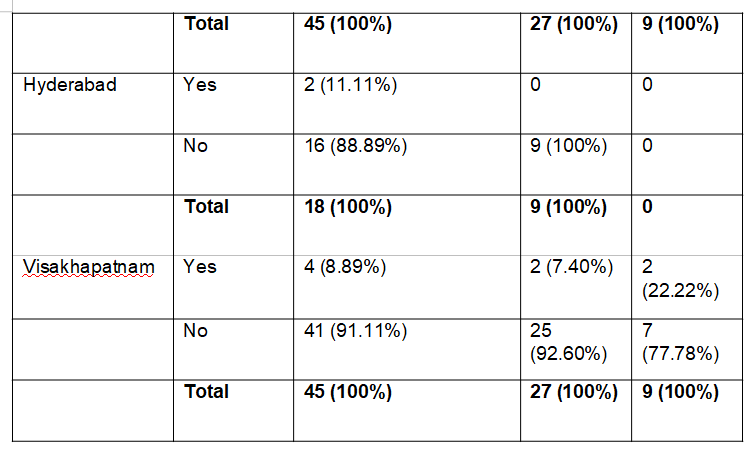

In rural areas, ownership of land and home is associated with social status and imparts “standing”. In times of need, a person who owns property can approach a financial institution more confidently as he or she has collateral to offer. Conversely, someone who does not possess “worthwhile” assets can fall prey to loan sharks. The table below illustrates the situation in three districts of Andhra Pradesh—Anantapur, Hyderabad, Visakhapatnam—studied over 2012-14.

The type of house one resides in is much more than status symbol. For a student, it could determine whether the atmosphere is congenial to study at home or not. A pucca house almost invariably connotes adequate living space and availability of facilities like electricity and running water. On the other hand, a hut or kuccha house may not have electricity and tap water. Lack of water can oblige most female members to help bring water from outside sources, which may erode the time available for study.

Electricity is an important index of the quality of life of any community, and a symbol of its level of development. Electric supply does not only make life more comfortable; it also makes it easier for students to study at night. An encouraging feature is that 92.59% of Scheduled Tribe households in Anantapur and 81.48% in Hyderabad said they have electricity as a source of lighting, compared with only 76.54% of respondents from Visakhapatnam.

Presence of a domestic toilet can also be regarded as an indicator of the level of education of the concerned person. A toilet is not only about good sanitation practices, but also entails dignity and safety of females, who face a greater risk of insect/reptile bites and molestation than males when forced to defecate in the open. Here, this author’s study finds, 46.91% of the respondents in Anantapur, 44.44% in Hyderabad and 50.62% Visakhapatnam stated they have domestic toilets. The alarming fact was that the largest number of respondents (STs, 56.9% and others, 62.2%) reported defecating in the open.

The communications revolution has taken root in education as well. This is clear from the higher proportion of positive responses on ownership of phones/mobile phones. While more than half of all social groups reported owning a mobile phone, 88.88% Scheduled Tribe families in Anantapur; 85.19% in Hyderabad and 88.88% in Visakhapatnam said they had a mobile phone. The corresponding figures for non-SC/ST respondents emerged as 59.26% in Anantapur, 77.78% in Hyderabad and 70.37% in Visakhapatnam). This establishes that residents understand the need to stay instantly connected with their associates. For students, it can be useful for discussing issues regarding their studies.

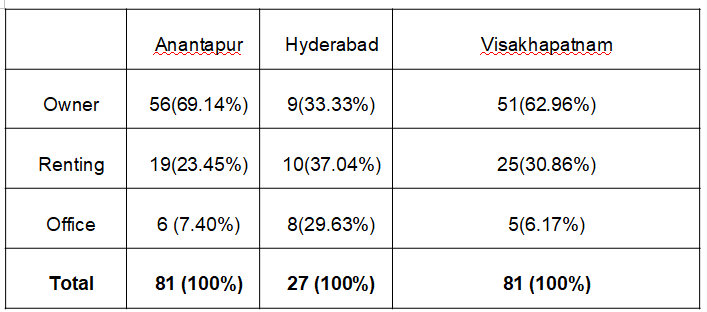

Difficulty in getting admission

One impediment to universal access to education is difficulty in getting admission. This may be largely due to unhelpful attitudes of concerned administrators.

A very encouraging factor is that respondents in all school categories almost unanimously said they did not find it difficult to get admission in a school. This shows that, generally, school authorities were not discriminatory during admissions. A major hurdle to admissions, then, could have been their insistence on production of documents which were not readily available.

Perception of pedagogy and education

Our education system works like a “banking system”—largely a one-way process. Students are depositories and teachers the depositors. The general tendency of many teachers is to “deposit” knowledge, which students are supposed to patiently receive, memorise and repeat. This approach can lead to lack of creativity and knowledge. The study sought to ascertain how well the education system is meeting the felt needs of tribal students and the degree to which it is socially relevant to them.

As regards teaching methods, an ideal teacher would target the lowest common denominator of the students and make efforts to ensure the lessons are properly understood by majority of the students. After all, a school is not a forum for a teacher to parade his or her knowledge. A good teacher must also encourage students to ask questions and seek clarifications before moving to another topic. Teachers should serve as friends, philosophers and guides for the students and not instil fear in them.

A related issue is the medium of instruction: a number of students may not be very conversant with even regional languages, leave aside English. These languages would be very difficult for such students to understand. Ideally, the teacher should be able to lapse into the local language of the majority of the students to make the lesson more interesting. After all, learning should be a pleasurable experience and not something which is forced from above. During personal interactions with student respondents in the study areas, it emerged that many are too scared to respond to questions teachers ask. A possible reason is fear of being humiliated in case their answers are wrong. Such a scenario is definitely not conducive for effective teaching-learning.

During the study, it emerged that cordial relationship can remove the fear psychosis and shyness of students. This enables teachers to understand students better and can check dropout rates, improve participation and strengthen the education system.

Various studies have found that some teachers take the initiative to address student’s problems regarding the coursework. However, more often, tribal students are hesitant to approach teachers even if they have doubts. Private tuitions are not a viable option for them, since most households may not be able to afford these.

Conclusion

Education is the key to tribal development, but tribal children have very low levels of participation. The development of tribes is taking place in India, but the pace is slow. If the government does not take drastic steps, the status of education among tribes will continue to be pathetic. Hence it is time to move beyond the “banking system” of education and provide more avenues for Scheduled Tribe students to engage with education.

Government educational institutions need to be sensitised to find ways to retain and promote tribal students. Acknowledging and preserving their culture and integrity is a valuable asset for a tribal child. It is necessary to revisit pedagogy and curricula and fine-tune them in accordance with the aspirations and felt needs of tribal students. Schools must sensitise, assimilate and incorporate tribal culture and values. In doing so, education can become an interesting and enjoyable learning experience for all students. Schools and colleges would then become incubators of change. New National Education Policy 2020 ignores the old problems of socially and economically backward and marginalised groups and especially Adivasi socio-cultural Identities. It is no solution to push marginalised students out of the mainstream and create labourers out of them in the guise of vocational training.

The author is head, Centre for Human Rights, Department of Political Science, University of Hyderabad. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.