A Not So 'National' Education Policy

The final version of the National Education Policy is out in public domain; although, it still needs the final approval of the cabinet to be called as the country’s official policy for education. The demands for a new education policy which addresses the fast changing education system were in the offing for some time, as the previous policy—enacted in 1986—was revised in 1992, leaving much needed changes in course correction. So, how is the new policy different from the previous draft released in May this year and what would be its implications? The 55-page document talks about a vision of school education, higher education, and vocational and professional education through the use of complicated words and emphasising connotations. But a thorough reading of the document reveals glaring gaps, which point towards exclusivity in the education sector.

Large Schools and Problem of Accessibility

An interesting but significant departure from the existing mode of education comes in the form of large school complexes with shared campus including libraries, laboratories and even teachers, likely to be built across the country. Section 7.7 of the draft reads, “The aim of the school complex will be to: a) build vibrant communities of teachers, school leaders, and other supporting staff; b) better integrate education across all school levels, from early childhood education through Grade 12, as well as vocational and adult education; c) share key material resources such as libraries, science laboratories and equipment, computer labs, sports facilities and equipment, as well as human resources such as social workers, counsellors, and specialised subject teachers - including teachers for music, art, languages, and physical education - across schools in the complex; and d) develop a critical mass of teachers, students, supporting staff, as well as equipment, infrastructure, etc. - resulting in greater resource efficiency and more effective functioning, coordination, leadership, governance, and management of schools in the schooling system.”

The subsequent sections talk about the management of the campus. While the argument given is the optimal utilisation of resources, a major concern remains about the the accessibility of children as major facilities are likely to be centred in these complexes. The example of science stream schools easily to comes to mind as these schools are often centred in urban areas forcing thousands of students to travel far. In the national capital itself, only one-third of the schools are offering science stream in higher secondary classes (Class XI- XII). The ratio further dips in relation with other states.

Also read: Why National Education Policy May End up Being a Missed Historic Opportunity

Another reason the whole provision of large school complexes is being furthered is to cut down the number of small schools providing education in remote and tribal areas. The policy talks about small schools being "economically suboptimal and operationally complex". Thus, the best possible remedy for these schools can be to consolidate these schools by creating large school complexes.

However, the consolidation of such schools, or merging the schools, to make them economically viable comes with a similar terminology used earlier by the Ministry of Human Resource and Development (MHRD) and Niti Aayog. In its letter in 2017, the MHRD had asked states to come for “rationalisation of small schools across the States for better efficiency”. But, the rationalisation process itself has brought havoc to students and their families in Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha. While 4,600 schools were merged in Jharkhand, a whopping 22,000 schools were merged in Rajasthan, effectively leaving thousands of students in the lurch as they were forced either to travel far for studies or drop out.

An independent study by Accountability Initiate (AI) maintained that Rajasthan saw a 6% decline in enrolment of backward social groups including Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Castes (OBCs). More importantly, the study highlighted that the stakeholders in the process namely teachers, principals and parents were never consulted.

Curtailing drop out rates with a compromised Right to Education Act

Beginning with a brief section on Early Childhood Care and Education, this part talks about the dismal drop out rates and the country's failure to retain children in schools. Section 3.1 under this states, “One of the primary goals of the schooling system must be to ensure that children are actually enrolled in and attending school...However, the data for later grades indicates some serious issues in retaining children in the schooling system. The GER [Gross Enrolment Ratio] for Grades 6-8 was 90.7%, while for Grades 9-10 and 11-12 it was only 79.3% and 51.3%, respectively - indicating that a significant proportion of enrolled students begin to drop out after Grade 5 and especially after Grade 8. As per the annual Educational Statistics published by the Ministry, an estimated 6.2 crore children of school age (between 6 and 18 years) were out of school in 2015.”

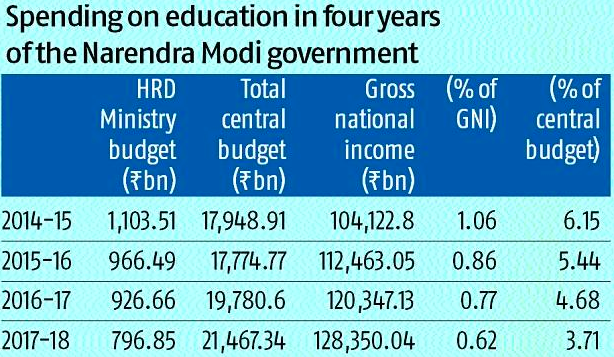

For years, experts have been opining that the drop out rate can be curtailed only if the reasons for drop outs namely as lack of interest in studies, rising costs of education in remote areas and engagement of child labour in labour intensive industries are dealt with. An effective way to bring back these children to schools is by extending universal coverage to class XII for impoverished students under Right to Education Act. The extension of coverage under RTE was mentioned in the previous draft. However, the provision seems to have been thrown into cold storage as the government appears non-committal on the issue. A similar position appears on financing where it advises that the expenditure component should be extended to 6% of Gross Domestic Product but it does not bound the Centre and states in any manner.

Higher Education- from Crumbling to Beleaguered

An intriguing part of the final policy reveals a common phenomenon; the obsession of the large. Not only does it advocate for large school complexes, it also advocates for mammoth higher education institutions with thousands of student enrolments. Under the section, Institutional Restructuring and Consolidation, sub-section 10.1 notes, “The main thrust of this policy regarding higher education is the ending of the fragmentation of higher education by moving higher education into large multidisciplinary universities, colleges, and HEI (Higher Educational Institution) clusters, each of which will aim to have upwards of 3,000 or more students."

Also read: New Education Policy: RTE Pruned, Research Market Based

The policy document mentions the names of Taxila and Nalanda, even the elitist Ivy League Universities as its source of inspiration. But a more perturbing trend could be noticed on two broad themes of autonomy and research driven by market forces. The policy strongly advocates that “all colleges shall eventually become Autonomous Colleges, which are large multidisciplinary institutions of higher learning primarily focused on undergraduate teaching. A college should, therefore, either be an autonomous degree granting institution, or a constituent college of a university - in the latter case it would be fully a part of the university.” (Section 10.3)

However, the entire phrase has made teachers sceptical about the trajectory of implementation of the policy. Saikat Ghosh, who teaches English at Shri Guru Teg Bahadur Khalsa college, Delhi University, told NewsClick that the provision of autonomy for colleges come with a new set of administrators called as "Board of Governors" responsible for every major decision regarding the institution.

He said, “There are no specific rules for members who will constitute the board of governors. It can be any person who may or may not have been associated with the academics. Secondly, they can decide a teacher's pay scale, salary or increments, meaning complete removal of existing rules regarding remuneration. Till date, universities were following the recommendations of pay commissions formed by government. Thirdly, the democratic decision-making bodies like Academic and Executive Council may be done away which would be a set back for discussion and dialogue within the campus. Most importantly, it pushes for private takeover of public resources. When it pushes autonomy for colleges, what it means is that the college may be deprived of affiliations from a university. Now, we all know students come to the national capital to study in Delhi University irrespective of colleges. Once the affiliation of colleges are stripped, there may not be many takers for not so popular colleges like Ram Lal Anand or Shyam Lal College. Once it happens, it might bring down the shutters on these colleges making them available to be taken over by private sector. "

Snatching Education from States

Taking a step back from the previous draft, the new version mentions about establishing a central National Education Commission/ Rashtriya Shiksha Aayog under the chairmanship of Minister of Education. The commission will have members from the ministries concerned with education, few members from states as state education ministers and other eminent personalities. In the document, the policy suggests that the new body will replace the Central Advisory Board on Education which failed to deliver its duties.

The policy recommends the “creation of a Rashtriya Shiksha Aayog (RSA) / National Education Commission (NEC) as an apex advisory body for Indian education, duly replacing the Central Advisory Board on Education (CABE). The existing CABE mechanism has added a lot of value to the Indian education system, but has fallen short of leading the much needed radical changes required for a great leap forward; not only was CABE an ad hoc body that was unable to meet regularly, but was not having any expert body to work on key matters on a continuous basis."

Also watch: Students Speak Up Against NEP

However, educationist Anita Rampal, formerly teaching at Faculty of Education in Delhi University, finds the entire arrangement disturbing and an encroachment on other states' jurisdiction. Talking to NewsClick, she said it is absurd to say that CABE did not function properly. She said, “It was an advisory body which had very little role. Since education is a subject matter of concurrent list, the new body deprives states of rights in deciding the affairs of education they want. The education commission directly under the education minister will leave very less scope for dissenting voices to emerge."

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.