Political Scientist Neera Chandhoke on the Preamble, its Promises and their Betrayal

Just about a year ago, protesters against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, had made public readings of the Preamble to the Constitution of India a form of protest and a reminder to the government to adhere to the principles enshrined in the Constitution. On 26 January 2021, the country will mark the 72nd Republic Day against the backdrop of farmers also raising similar concerns. Neera Chandhoke, Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Equity Studies and former professor of Political Science at the University of Delhi, talks to Newsclick about why the Preamble has become a means to foster fraternity among ‘we the people’ and a historical and political document to affirm popular sovereignty.

During the anti-CAA protests last year, people were reading out the Preamble to the Constitution at Shaheen Bagh and other sites all over the country. Why do you think people chose to read out this document?

We must understand the protesters’ choices historically. While students are taught in college that the Constitution is an extension of the Government of India Act, 1937, which was passed by the British Parliament in 1935, the freedom struggle had already given final shape to a Constitution in the preceding decades. The Indian National Congress had mobilised thousands of people as a movement, and through the All Parties Conference it came up with a robust proposal for a Constitution in 1928 [the Nehru Report]. This document embodied our aspirations as a people.

This all-party committee was set up after eruption of widespread discontent with the Simon Commission [1927]. The committee had a number of distinguished lawyers and jurists, who drafted this Constitution. It gave us two or three things in writing. The first was universal adult suffrage in 1928, which was when, after many decades of limited franchise, England had finally given universal adult franchise too. If memory serves me right, Motilal Nehru had said at the time that though a number of our people are not literate; they will acquire education in democracy through the exercise of their franchise. So, there were such buoyant hopes in the political classes and in the public at the time.

The second contribution of the Motilal Nehru draft Constitution was that it had given an integrated list of fundamental rights including the right to a reasonable income, the right to form associations and so on. These have been integrated into our Constitution. Social rights, such as the right to a living wage, health and primary education, were adopted in the Constituent Assembly on December 1946 and when the Constitution was finally adopted in 1950, they were integrated into two chapters—on Fundamental Rights and Part IV, on Directive Principles of State Policy.

Of course, Jawaharlal Nehru found its provisions inadequate; he thought there should have been more equitable redistribution, but that was also a younger person revolting against the senior generation that had drafted the Constitution. The fact is that members of the All Parties Conference were very influenced by workers’ movements in Europe and wanted to include these rights.

What is the significance of the history of framing the Constitution?

The Nehru Report becomes the draft which reflects in our Constitution’s provisions. For example, the 1931 Karachi Resolution on Fundamental Rights came after the March 1931 Kanpur riots, when Mahatma Gandhi said the state will practice neutrality towards all religions. Earlier, the All Parties Conference also addressed the question of producing a Constitution that satisfies both Hindus and Muslims. It went to the Muslim League and asked them to participate in the formation of the Constitution. The Muslim League said they would like separate electorates for Muslims. The leaders did not agree to separate electorate, but they talked about state neutrality towards religion, which we recognise in the Constitution as secularism and special rights for minorities, such as independence of institutions and protection of minority languages.

So, the main principles of the Constitution had been already enacted by the freedom struggle, and that became the Preamble of the Constitution. To read that Preamble is to read the Constitution historically, as a product of our freedom struggle. It is to remind everyone that India, despite illiteracy and poverty and backwardness is in pursuit of certain aspirations.

Was it not a small section of elite, through membership in the Constituent Assembly, who gave India its Constitution?

In the 1920s, the Congress transformed from being an upper-class party to being a mass party under the leadership of Gandhi. You have the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920-21, the Civil Disobedience movement in 1930-31. Gandhi believed that the British could not continue to run the government unless the people cooperated with them. So, the idea of non-cooperation from not paying taxes to not taking office, aroused tremendous mobilisation in pursuit of the cause. Tens of thousands of people would mobilise whenever Gandhi called.

This is precisely how liberal constitutionalism has developed in the rest of the world—with a focus on political rights, civil liberties, right to self-determination, etc. Unfortunately, the other side of Independence was Partition. We have to understand that this Constitution is not just the product of jurists and lawyers, but also a result of popular mobilisation.

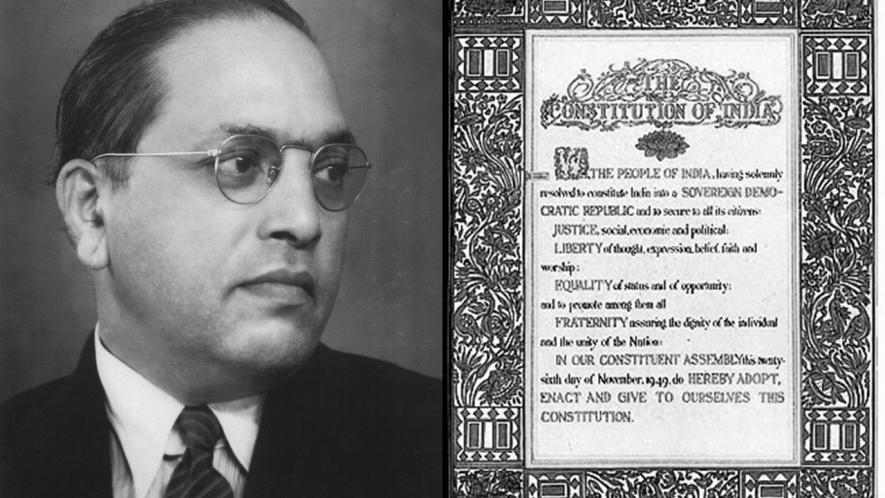

In 1946, when Nehru was interim prime minister, he identified across the country notable jurists, from Ambedkar onwards, to come and help the Constituent Assembly draft the Constitution. Yet it is not just the lawyers who wrote the Constitution, it is the product of a very meaningful historical movement against colonialism, against un-freedom.

You mean that those who protested by reading the Preamble, which begins with the words ‘We the People of India…’, were reminding everybody of that past and the primacy of the people in Indian democracy?

What these young people were doing as part of the anti-CAA movement was to say we are citizens of India by virtue of the fact that we are born here, we belong here, we obey the laws of the state, we pay our taxes, our parents pay taxes, and we do not have to produce documents to show that we are citizens. This is a stand that has been taken by demonstrations across the world, in Europe particularly, by the migrants, for instance. They are saying that we reject papier [paper] citizenship, we want performative citizenship. They are saying, I am a citizen of this country, I was born here, or I live here, study or work here, I obey the laws, so why are you [the State] rejecting me? Why are you saying I must prove I am a citizen? That was also the meaningful lesson of the anti-CAA protests.

One aspect the Preamble stresses on is fraternity, that there should be fellow feeling between people. Has this really developed in India?

That is indeed a lesson from the anti-CAA protests; that even though we are not affected by the new citizenship law, we are protesting on behalf of our fellow citizens. For example, many Hindus will probably not be affected by the National Register of Citizens [mandated by the 2003 amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955, and sought to be implemented countrywide by the present government]. Yet, they expressed solidarity with the Muslim community which was very alarmed that it might be stripped of citizenship. The Muslim community was particularly concerned since the politicians were saying again and again that we are going to follow the CAA with the NRC.

Why did people feel the Preamble was the document to give voice to solidarity?

This is the third important aspect of those protests. First, that protest was spontaneous, not organised by a political party or even by NGOs. There were many big mobilisations during the first term of the United Progressive Alliance government from 2004 to 2009, when [progressive] legislations guaranteeing right to work, right to food, right to primary education and right to information, were passed. At the time, the NGOs would lobby parliamentarians and the media to have these laws passed, but there were no NGOs organising the anti-CAA protests. People were joining it spontaneously, especially women. We can see how important and politically-relevant elderly women have become since that movement. This is why the Preamble is so precious to us. It created space for a reiteration of popular sovereignty in a country that tends to have a very feudal political culture.

The Preamble also mentions “Justice...that is political”. What is political justice and how do people secure it?

The Indian Constitution is a historical document, but like all constitutions it is also an aspirational document. The anti-CAA protesters were saying that we are the locus of sovereignty and you, the government, are our elected representatives. Farmers are saying this too with their protests, that the government must listen to them because they are our representatives.

An assertion of the power of we the people of India who have given to ourselves the Constitution acquires importance because these protests are saying that we have elected you, you are responsible to us, and accountable to us, and if we do not like the citizenship legislation then you please withdraw it. They are doing this non-violently, and that is their importance.

One challenge for governments is that a group would say it does not like a law, but another group or mobilisation would say they want this law. How does the Preamble help navigate this?

You have to understand that politics is a contested field in which you will always have different points of opinion. It is a field where you want power but that power is contested. You do have to distinguish between popular struggles and those struggles that come up to defend the government, in the sense that the latter are obviously party people and so on... the government may want to choose farmers’ organisations which are not concerned about the Minimum Support Price to represent it in discussions about the farm laws. Even so, this is a matter for farmers’ organisations and social movements to negotiate. The government also has to negotiate with minority opinion—it cannot just say that their opinions are unimportant.

So, while the protesting farmers are contesting the government, they are also contesting the right of the minority opinion to represent the entirety of “farmers”. Therefore, government would have to negotiate with other points of view, and movements have to negotiate too. The women’s movement has had to negotiate; and it has a multiplicity of voices. There cannot be one farmers’ voice, just like there is not one voice in the women’s movement. If there is a minority opinion then it is the duty of the leaders of the struggle to negotiate with it. They have to create a consensus, while the government, too, cannot say, we are right and you have to follow any laws we make.

If you are striving as a country for social and economic justice, is it possible to do so without circumscribing some rights, especially of the elite?

We must remember that both the December 2019 [anti-CAA] movement and the November 2020 [farmer] movement are not raising radical demands. They are not seeking land redistribution, nor are they raising the earlier radical demands for more land or more wages. They are simply saying, give us what the Constitution promises.

The farmers have raised a very important point—that laws must be passed procedurally; you cannot just rush a law through Parliament and think it is binding. The legitimacy of a law depends upon the government adhering to certain procedures, which they obviously did not follow because the three laws were passed in a rush with the Opposition not being allowed to speak and so on...

Now, on whether you can have social and economic justice without affecting the rights of the better-off…in the Scandinavian countries, workers’ movements have negotiated with peasant organisations and the Social Democratic Party [for example, in Sweden] to create a consensus that people of a certain strata should be taxed at about 50%. The taxes are therefore huge, and that is how they have built up their social democratic stature quite well. In England as well, there has been progressive taxation until the time Margaret Thatcher took over. But now the scene is different; we are no longer living in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 and collapse of a socialist society—am not saying collapse of socialism—and we no longer have the widespread approach that the rich have to pay for the poor. Now, I think, you have to build a consensus for higher taxes on the rich, and that has to be thought out in quite a different way from the earlier ideas of redistribution. It has to be in terms of obligations we owe our fellow citizens, and so on.

It is very evident that Indians still have communal feelings, and there still is caste conflict. So, have we failed to live up to or evolve with the Preamble?

In all the literature about India’s past, you will read that people have lived together for centuries. They may not dine together, and may not inter-marry, and yet not kill each other. This might be a very vulgar kind of an argument, which has a grain of truth in it, that a sentiment that I want to have nothing to do with a person or community does not mean that I kill that person or members of their community.

Very unscrupulous elements—who may not be politicians but agents of communalism who serve a political agenda—do not want people to live together and they can manipulate public sentiments. The BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] is not the only party in whose time this has come up. The Congress is also responsible for some of the worst communal riots, the anti-Sikh riots in 1984 for example.

You must let people build bridges with each other—through trade unions, through education—but you are instead dividing people because that would create vote-banks. The killing only happens when there is a trigger, it might be an inflammatory speech, it might be money being paid to these agents to spread violence... Look at the provocative speeches given before the communal violence in north-east Delhi in February 2020. Those who gave those speeches have not been brought to book, and instead many who were actually trying to save the victims have been arrested. And there is a danger that others would be picked up at any moment, the way young people have been picked up in Jawaharlal Nehru University, Jamia Millia and Delhi University. Therefore, what we need is to find out who benefits from casteism and communalism.

As for casteism—it is there, but I think it is also politically very expedient for any ruling party to take advantage of the social cleavages.

How have other countries navigated these cleavages?

I was reading about Nelson Mandela in South Africa, who comes out from prison while the country is transiting to majority rule, and the first thing he says is that the whites have an equal chance to live in this country. Now, the whites had wreaked injustice on the Blacks, but Mandela says—reconcile. Mandela also reminds the Blacks that they are equal citizens, and they have to reconcile with whites as equal members of a political community. I think Mandela should be a model for all divided societies. He did not tell the Blacks [to] go and kill the whites! He said the whites will stay, as equal citizens.

Then Mandela set up the Truth and Reconciliation commission, in which whites could ask for amnesty if they confessed to their crimes done in the public (and not personal) sphere. It served a psychological purpose. It allowed people to accept each other. At least there was no civil war in South Africa, as international commentators had been saying there would be. Mandela asked people put away their hatchets, their instruments of violence... Reading this reminded me of [Jawaharlal] Nehru during the Partition. Mandela [however] managed to stem a civil war. That is a very big political miracle and this is statesmanship. And on the other hand, you have politicians who will pump passions at the drop of a hat. In a very unequal society [such as India’s], economically and in terms of religious and caste considerations, it is perhaps very easy to put the blame on another community and incite people to violence.

Will a truth and reconciliation commission work in India, especially considering the wounds of Partition are yet to heal?

Today [in India] we do not talk about British colonialism, which changed us in many more ways than earlier rulers—they changed the way we think! But you cannot have [reconciliation] unless you have a set of leaders who are committed to let people live together.

India became a sovereign democratic republic through the Constitution, and later spelt out socialism and secularism. Can India remain democratic if it is not socialist and secular?

We are reducing democracy to elections in India, but elections are only one moment in the life of a democracy. All governments have to abide by certain values. Of course, there is no fixed definition of socialism, but it means that people must have equal chances to opportunity, a chance to invest their energy in education, in training, and it is for the government to provide people with these opportunities—not just [opportunities] in the religious sphere. We also see unabashed admiration for capitalism in the country, without any understanding of it. Karl Marx had said very perceptively that the task of a capitalist state is to save capitalism from the capitalists! For, if the capitalist wants to overwork the workers you are going to have a revolution on your hands! So, you have governments step in to ensure a living wage, holidays, to regulate hours of work, provide education, health, etc., as they do not want workers’ discontent.

How can we live together? Recently, I watched the swearing-in of the new American President [Joe Biden], and a discussion about all the Indian Americans who have got into positions of power in the United States. I am not denying racism in the US, of which there is a lot, but the system has allowed these people to take advantage of opportunities. Look at the number of Indian CEOs in the United States—why is it that a Dalit cannot do as well in India? Getting a chance within the structures of opportunity is called socialism, or equity. As for secularism, well, that seems to simply of no interest to the party in power.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.