Repackaged Laws for Decolonization Game

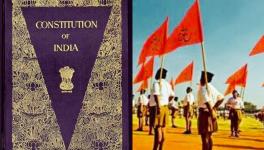

On the eve of the 77th Independence Day this year, Union Home Minister Amit Shah tabled in the Lok Sabha Bills to amend three colonial-era codes on which the criminal justice system rests, spinning this as a belated blow in favour of decolonisation.

The three enactments were the Indian Penal Code (IPC, to be renamed Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita), the Code of Criminal Procedure (Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita), and the Indian Evidence Act (Bharatiya Sakshya). It could be argued that these had long become obsolete, anachronistic and against the zeitgeist in ways that hammered democratic, civic and civilizational progress.

But actually, the bills just repackage our criminal justice system to create the basis for a far more authoritarian order. There is something ironic in this enterprise: the more the regime becomes colonially authoritarian in its political content and style, the more anti-colonial its rhetoric becomes.

Not content with tabling new Bills that remained as draconian, albeit with Sanskritic names, the current dispensation seems to be groping its way towards renaming India Bharat by proxy, as a couple of formal invites related to the G20 Summit attempted to do.

This is supposed to be an anti-colonial politics of substance, but given the Bills tabled (now referred to a parliamentary committee) and the invites were resolutely in the mimetic English of colonial bureaucrats, the ineluctable conclusion is that they are purely gestural—prompted in no small measure by the smart choice of acronym on the part of the opposition alliance, INDIA.

Champions of constitutional liberties and democratic values have been running a campaign against Section 124A of the IPC: the so-called Sedition provision. The arguments against it are mainly that there should be no restriction on free citizens criticising the government in whatever way they choose to as long as their criticism is theoretical since that is the essence of the compact between the state (and the government of the day) and the citizen; and, second, that Section 124A is being used to crack down on citizens in an extremely authoritarian way, which is ripping up the postcolonial, constitutional contract.

Ironically, those who promote, sanction and underwrite a violent recourse to extreme authoritarianism are the most vocal about anti-colonialism, which they promote in a number of either symbolically puerile ways or by using rhetoric to gaslight the nation and distort its history.

The amendments, sold as a libertarian initiative, are a medicine far worse than the disease, though Shah, while introducing the amendments, said they would not be punitive but promote justice whilst waffling about something called the ‘Bharatiya atma’. But before this, we must deal with the challenges to draconian laws, based on which this regime has swiftly built the momentum for both a Hindu Rashtra and a police state.

Over the past few years, especially since the Supreme Court was or has been led by Justices UU Lalit and DY Chandrachud, a number of challenges relating to sedition and related matters, including arbitrary detention and the scattergun use of preventive-type legislation like the UAPA, have been brought before higher courts and the top court, which have been almost uniformly critical of these draconian pieces of legislation. In 2022, the Supreme Court temporarily kept Section 124A in abeyance. On 6 September 2023, TheTelegraph reported, ‘SC lays down preventive detention guidelines’.

There is very little doubt that given an unfavourable judicial climate, in which the regime cannot hope to get away with whatsoever may take its momentary fancy, the initiative to amend the three colonial-era laws is precisely to rearm the apparatuses of the state with the unbounded, unquestionable legislative provisions of the colonial state and reaffirm its organic separation from the citizenry.

Let’s make a small comparison: The old Section 124A, mercifully brief, said, ‘Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law in India, shall be punished…’

Section 150 of the new avatar says: ‘Whoever, purposely or knowingly, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or by electronic communication or by use of financial means, or otherwise, excites or attempts to excite, secession or armed rebellion or subversive activities, or encourages feelings of separatist activities or endangers sovereignty or unity and integrity of India; or indulges in or commits any such act shall be punished…’

Let’s examine a few other ‘amendments’. The Bill retains criminal defamation. Think of it. In a country where taking offence and having your sentiments hurt, often leading to criminal persecution under the guise of prosecution, is a cottage industry, this would be a windfall in the hands of a malignantly minded state. As has been pointed out, comedy, satire and irony could become criminal offences.

Similarly, the definition of terrorism stands hugely enlarged. Anyone can be persecuted for being a ‘terrorist’ if they do one of a number of listed things, which include causing ‘extensive interference with…critical infrastructure’ or provoking or influencing ‘by intimidation the government or its organisation in such a manner as to cause or likely to cause death or injury of any public functionary…to compel the government to do or abstain from doing any act, or destabilise or destroy the political, economic, or social structures of the country, or create a public emergency or undermine public safety’. Death by unintelligibility and obfuscation. This omnibus definition could make you a terrorist if you participated in a street protest, mobilised against a thermal power plant, or sat on railway tracks to press legitimate demands.

In its new form, the IPC prescribes the death penalty for lynching and sexual assault against minors, as well. We’ve been through this argument. Stringent punishment encourages greater brutality. We already have laws against assault. First, catch the culprits, then punish them. In today’s climate of impunity, the death penalty is playing to the gallery. And will illegal police ‘encounters’ qualify as lynching? They are, after all. Uttar Pradesh would find itself with a serious personnel problem.

Some other amendments are procedural, especially the ones concerning the Evidence Act, though some of the features of the new Criminal Procedure Code, such as those related to access to electronic material, could cause disquiet.

Though the presumption of innocence remains at the heart of the criminal justice system, its perversions remain—not created by the current regime but relentlessly misused by it. There had been talk of a review, risibly. In the cases of terrorism (Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act), drug-related cases (Narcotic Drugs and Psychedelic Substances Act) and money laundering (Prevention of Money Laundering Act), you need to prove innocence to either avoid detention or get bail.

In the Bhima-Koregaon case, of the 16 arrested, Stan Swami passed away in custody, and five years on, a majority is still languishing in jail. Whatever happened to bail being the norm and jail being the exception?

The author is a freelance journalist and researcher. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.