Some Personal Reflections on Prison Medical Care

Courtesy: Arun Ferreira

I have spent almost eleven years in detention, with considerable periods in the most populated prisons of Maharashtra. My first incarceration from 2007 to 2013 began shortly after I turned fifty. I had a second stint from 2018 to 2023, while I was in my sixties.

Perhaps because of my somewhat advanced age, I could not help but pay particular attention to the medical facilities in the prisons where I was lodged. During the Covid pandemic, I spent a significant amount of time in the Taloja Central Prison Hospital as a caregiver for two octogenarian co-accused prisoners, Professor Varavara Rao and Father Stan Swamy. This provided further opportunities to observe the prison health system at close quarters.

Anecdotal inputs from fellow prisoners who had experience of other jails filled out my picture of what passes for medical care in prisons in Maharashtra. The observations are obviously very one-sided and could even be branded by some as biased.

It is the view from behind bars. It may even be regarded as the view of the ‘criminal’— alleged or actual. But listening to voices from the other side can always help understand a given reality more accurately.

Torture and the doctor

Let us start with an example of my prisoner bias against jail doctors. It was the day of my first entry into Yerawada prison in 2018, with my co-accused Arun Ferreira, who also happens to be an advocate.

My first incarceration from 2007 to 2013 began shortly after I turned fifty. I had a second stint from 2018 to 2023, while I was in my sixties.

Arun had complained to the court about being beaten up in police custody and we were aware that he would be presented before the medical officer on duty. It was past 10 p.m. and the doctor was not on the campus and had to be specially summoned.

As he bent through the wicket gate at the entrance, we noticed that the doctor had to be supported by prison guards on both sides. Both of us, having been to prison before, had developed a poor opinion of prison doctors in general and immediately assumed that he was more than a couple of drinks down; but we were horribly wrong.

He did his job competently. We later learnt his unsteadiness was due to some affliction and he was actually a very dedicated and humane person, a gem in the otherwise mucky arena of prison medical care.

Our bias at that moment was coloured by earlier experiences of doctor responses to custodial torture. I had, in 2008, been a prisoner who witnessed the particularly brutal beating of some Muslim prisoners by the jail authorities at Arthur Road Prison.

The inquiry by Mumbai’s principal sessions judge then had found that their injuries as shown in the medical certificate issued by the jail doctors were “manipulated in order to help the jail authority”.

The Bombay High Court had found the role of these doctors to be “reprehensible and shameful”. Similarly, when a woman prisoner Manjula Shetye was tortured and beaten to death by jail staffers in the Women’s Prison at Byculla, Mumbai, the investigation revealed that the jail doctor had given a certificate falsely stating that there were no visible injury marks on her body.

These reported abuses represent the tiny minority of cases that actually reach the stage of investigation, inquiry and the courts.

Rule 3(2)(38) of the Maharashtra Prisons (Prison Hospital) (Amendment) Rules 2015, formulated from the Model Prison Manual, 2003 stipulates that it is the duty of the prison medical officer to “report to the additional director general of police (prisons) or inspector general of prison through the superintendent of the prison if he notices injuries on any prisoner which are alleged to have been caused by prison officials”.

Torture and beatings by prison officials are a regular occurrence and I have sometimes been an eye witness and very often an ear witness to many a beating.

Torture and beatings by prison officials are a regular occurrence and I have sometimes been an eye witness and very often an ear witness to many a beating. The Gandhi Yard of Yerawada Prison, which was the prison authority’s favoured space for inflicting corporal punishment, lies next to the Phansi Yard (Death Row) where I was lodged.

The ear-piercing screams of the victims next door was a regular feature of my period there.

When beatings severely injure and incapacitate the prisoner, he is typically moved to the prison hospital.

However, I have yet to hear of any medical officer performing his duty under Rule 3(2)(38)— at least nothing has entered the public domain in the eight years and more since the rule was notified in December 2015.

The widespread connivance of doctors in torture has been extensively documented and analysed. In discussions behind bars regarding such complicity, the general understanding is that jail doctors do it because of the commonality of interest they see with other jail staff.

However, this behaviour can also be seen in doctors at hospitals outside prisons, where such pressures are absent. My discussions in prison with several police torture victims indicate that though they were taken to government and municipal hospitals for statutory medical examinations during their period in police custody, no doctor at such hospitals was ever proactive about fulfilling the requirements of the law by recording any injuries or marks of violence as prescribed under Section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.

Even where the victim complained, there was always a reluctance, and often, a downright refusal to record the facts.

My personal experience in this regard is telling. My first encounter with the medical profession from the position of a prisoner was when I was taken to KEM Hospital, Mumbai, the day after I was picked up in 2007.

I had been roughed up and was under considerable pressure, but somehow mustered the nerve to tell the young doctor manning casualty what had happened.

He had already commenced the normal perfunctory exercise of certifying that ‘all is well’ and did not take kindly to my complaint. Barely looking up from his form he said, “Tumne bhi kuch kiya rahegaa [You too must have done something].”

The obvious implication was that, since I had been arrested, I was a criminal, guilty unless proved innocent, hence worthy of a bit of torture. Disgust writ large in my eyes, with inner rage approaching a tipping point, I coldly told him to do his duty and record the facts.

He read my eyes and body language with commendable accuracy and probably realised that I would not stop there, and would likely take it to court. He started writing, but not before signalling to the escorting police officers that he was doing it unwillingly.

When beatings severely injure and incapacitate the prisoner, he is typically moved to the prison hospital.

That experience broke the image of the noble medico which my childhood ‘family doc’ had personified and which had lasted into my graying days. That broken image has still not been mended.

Later prison experiences would not allow it. My crossing over to behind the bars has coloured my view. I have become ‘biased’.

Prison medication— illogical and anarchic

Prisons are institutions that have a logic of their own— or should I call it illogic? One such realm of illogic is the rules (unwritten) governing the system of medicine to be practised within prison walls.

These rules depend on the combination of the superintendent and chief medical officer (CMO) operating at a given time in a particular prison. One very common ‘rule’ has been the ban on the entry of non-allopathic medicines into prisons. Often such bans are imposed when most, or even all the medical officers of the prison have non-allopathic qualifications.

Thus, when, during my earlier stint in Nagpur Central Prison, I had tried to bring in ayurvedic medication for piles, which I had used outside, it was seized at the gate and confiscated.

The doctor who confiscated the medicines was himself a Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) and when I pointed out the irony, he made no attempt to provide any rationale— he merely smiled, pleading helplessness. I stayed helpless, sans the smile.

I had been roughed up and was under considerable pressure, but somehow mustered the nerve to tell the young doctor manning casualty what had happened.

However, my co-accused, advocate Surendra Gadling decided that silence was not an option. Before his arrest, he had been under the treatment of an ayurvedic practitioner for most of his chronic ailments.

While in jail in Pune, he obtained a court Order permitting him to take ayurvedic medicines into prison. However, after moving to Taloja prison, following a change in the prison superintendent, they were abruptly disallowed on the plea that prison policy only allowed allopathy within the prison— this at a time when all three medical officers, including the CMO, were BAMS graduates!

Gadling decided to seize the irrational bull by the horns and lodged a criminal complaint (Civil and Criminal Court, Panvel. Surendra Pundlik Gadling versus Umaji Tolaram Pawar and Ors. Cri M. A. No 261/2022) with the jurisdictional magistrate against the superintendent.

He argued that the abrupt cutting off of medication he had long been dependent upon was akin to withdrawing life support; therefore, in essence, an attempt to murder. Not surprisingly, his case has been ‘ongoing’ since 2022.

The illogical nature of the absolute ban on non-allopathic medicines should not, however, be taken to mean that there is a system and method for the use of allopathic medication in prison.

The dispensing of medicines for common ailments such as allergies, cold, conjunctivitis, headache, diarrhoea and constipation is normally done by prisoners and prison guards who move from barrack to barrack with boxes of tablets.

It is they who hear the complaint, make the diagnosis and decide the course of treatment. The tablets dispensed often depend on what is currently in greater supply, and more particularly, is approaching its expiry date.

The use of antibiotics is indiscriminate and given for a wide range of complaints. The average period for which the medication is given is two days. Self-medication is widely prevalent, with pills finding innovative uses. Many have told me they used Amoxycillin as a laxative.

I realised that quite a few commonly distributed pills were hoarded and consumed more for a side-effect than their prescribed use.

As for the prisoner with chronic illnesses requiring continuous medication, it is a struggle to even lay hands on a tablet they have been using for years.

I realised that quite a few commonly distributed pills were hoarded and consumed more for a side-effect than their prescribed use.

A considerable part of my time in the prison barracks was devoted to making repeated written applications to the CMO for patients with chronic conditions, who needed antihypertensives, insulin, anti-asthmatics, or some such necessary medication.

Many applications fell forlorn by the wayside. Most would consider themselves lucky to get half the dosage they had been prescribed outside prison.

Prison frailty and death

Rapid deterioration— from relatively good health to deep distress to a life-threatening situation and even death— is a process I was often witness to during my period in prison.

A particularly vulnerable section I observed at close quarters was the senior citizens of the Budda Barrack [Barrack for the Aged], where I was for over a year.

Most had some pre-existing chronic ailments such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma and arthritis, which they had learnt to manage in their life outside, but presented insurmountable problems in the prison world with its erratic availability of medicines, cramped, suffocating and filthy barrack conditions, and the ever-present risk of infections.

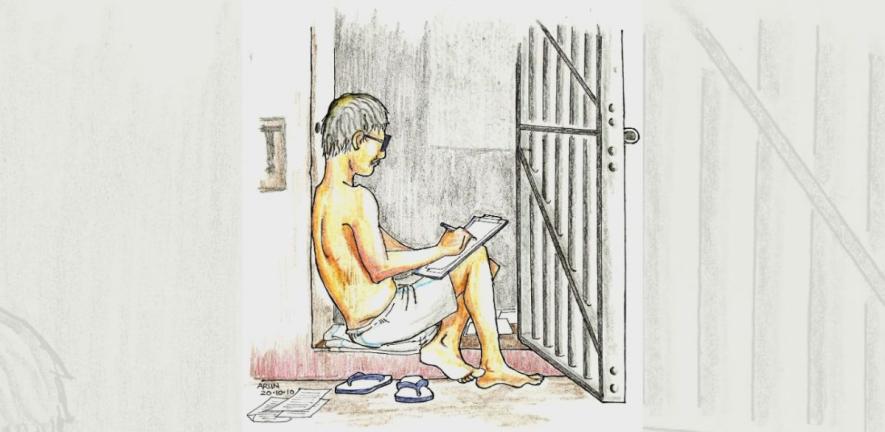

‘A’ was seventy-plus with diabetes and hypertension, but maintained a strict regime of controlled eating, sleeping, cleaning his immediate surroundings, prayer and continuous copious writing.

However, a sudden undiagnosed infection, combined with the rejection of his bail application, saw him quickly go downhill. The prison medical system had no answers for his condition.

His own solutions were peer-prescribed self-medication and more prayer and penance. The gap between a sturdy, determined, seventy-two-year-old and a corpse who had withered away was just about a couple of months.

‘B’, a thin, tall septuagenarian seemed to be in dire depression from the day he entered the barrack. The shock of prison squalor saw him abstaining from food unless coaxed by neighbours to eat. He was moved to the prison hospital, where he shrank into oblivion.

Due to the constant shortage of guards to escort prisoners, the very few who get sent to a hospital outside the jail are mostly those who can pay under the table.

‘C’ was a fit, agile man in his late sixties who regularly exercised until hit unexpectedly by some undiagnosed infection. His fitness rapidly vanished and he too became a prison hospital inpatient. He survived, but I doubt whether he will be able to overcome anything similar in future.

None of these had been sent at the appropriate time for hospital care outside the jail, despite being desperately in need of it. The case of Father Stan Swamy is well-known. He was sent to hospital only after court intervention, but it was too late.

Due to the constant shortage of guards to escort prisoners, the very few who get sent to a hospital outside the jail are mostly those who can pay under the table.

Those who have greater need but cannot pay are left behind until almost on death’s threshold. At times it is too late and the corpse is sent to the government hospital and shown as ‘dead on arrival’ (DOA).

I too could have met a similar fate during the monsoon of 2022. As an infection wracked my body and made breathing difficult, I quietly curled up on the floor of my un-ventilated cell in a corner of the damp moss-ridden Anda Circle building, only emerging once in a while to plead with the jail staff to take me to a hospital outside.

The CMO was however adamant that there was no need. A ruckus raised by my co-accused forced the authorities to take me before a visiting specialist in general medicine, who displayed dynamism and promptness I have never otherwise encountered behind prison walls.

Two minutes into her clinical examination, she sarcastically told my jailor-in-charge, “Aap bahut acche patient laye ho” [You have brought a very good patient].

She swiftly administered oxygen and other emergency measures, then countermanded the CMO’s Order to insist that I was immediately, under her watch, moved to the JJ Hospital, where I got appropriate care.

My lawyers moved applications, the media took note and the court monitored my treatment till my recovery. As has been well reported, Professor Varavara Rao, my co-accused, was saved by a similar intervention.

But this to me is no parable providing solutions; rather a tale that highlights our privilege. It is extremely rare to have the energetic co-accused, doughty lawyers and media interest that we evoked.

Need for systemic transformation

For the average prisoner, the resolution lies in more of a systemic change. “As an old and experienced prisoner, however, I believe that governments have to begin the reform… Humanitarians can but supplement government efforts,” wrote Mahatma Gandhi almost a hundred years ago, in an article on ‘Jails or “Hospitals”?’.

Post-1947, there have been numerous proposals of government-appointed jail reform committees, most notably the Mulla Committee Report of March 31, 1983.

It took twenty years for the Union government to report on its implementation, along with a Model Prison Manual, 2003. The Maharashtra Government took another twelve years to notify amendments to the Maharashtra Prison Manual accordingly, including the Maharashtra Prisons (Prison Hospital) (Amendment) Rules 2015, which somewhat diluted the 2003 manual’s standards.

Two minutes into her clinical examination, she sarcastically told my jailor-in-charge, “Aap bahut acche patient laye ho”.

According to these notified rules, the Central prisons, where I was lodged, should each have had a type ‘A’ hospital, with 50+ beds, and the following staff:

- One chief medical officer (in the rank of civil surgeon with post-graduate qualification).

2. Five medical officers (in the rank of assistant civil surgeons) from the following specialities: MD, general medicine; MD, dermatology; MD, psychiatry (mental and de-addiction cases), MDS, dentistry; MD, gynaecology.

3. Three staff nurses.

4. Two pharmacists.

5. Three nursing assistants.

6. Two laboratory technicians.

7. Two psychiatric counsellors (psychologists).

In the ninth year after the coming of these rules, no prison has complied with even a small fraction of these stipulations. No budgetary allocations seem to have been made yet for this purpose. Meanwhile, a new Model Prison Manual, 2016 reiterates the higher 2003 standards.

While the executive does nothing to implement the law, the judiciary’s attempts are fitful and ineffectual, with poor follow-through of its own orders. Re: Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons [Writ Petition (Civil) No. 000406 of 2013 (Cited 2023 Nov 13)] is a suo motu petition before the Supreme Court, ongoing since 2013, with no judgment for over five years.

The Bombay High Court, on April 13, 2022, directed [in Dr P. Varavara Rao versus National Investigation Agency and Anr. Criminal Writ Petition 461 of 2022. Paras 26 to 28 of Judgment dated April 13, 2022 (Cited 2023 Nov 16)] the inspector general (prisons) to report on the implementation of Rules concerning medical care but has not held a single effective hearing in the matter after that.

Meanwhile, the Union Home Ministry has released a Model Prisons and Correctional Services Act, 2023, to be adopted by all the states and has dropped the mandatory requirement of the Prisons Act, 1894, which currently governs prison administration— for every prison to have a medical officer and a hospital.

The new Act simply states that every prison “may” have a medical office. This seems like providing statutory sanction to the present miserable state of affairs, where several prisons lack a hospital or even a single specifically assigned doctor.

As I recall the words of that ‘old and experienced prisoner’ way back in 1926, I cannot see much hope.

This piece was first published in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics on March 29, 2024. DOI:10.20529/IJME.2024.021

Vernon Gonsalves is a trade unionist, activist and academic.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.