Spotted Goddesses Subvert ‘Difference’

Situated within the ambit of transnational feminisms, Roja Singh's Spotted Goddesses is an ethnography of caste, gender and Dalit women’s leadership. Singh describes strategies of social change in Dalit women’s activism as embedded in the urge to upend and subvert imposed identities of ‘difference’ in a mode of resistance which fearlessly thwarts social compartments and punishment traditions. Built around a powerful core which is primarily shaped by Dalit women’s songs, and oral and written testimonial narratives, including Singh’s personal story, this interdisciplinary work is a searing vindication of Dalit women’s right to rise and rage against the shackles of Brahminical patriarchy.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter "Spotted Goddesses Subvert 'Difference': Traditional Narratives and Punishment Ordinances" of the book.

Women Unlike Sita

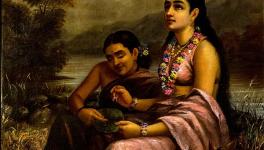

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Rama is a Kshatriya caste settler on an inhabited land. Valmiki establishes conquest in the epic as an entitlement to dominance by communities vested with power: materially, spiritually, physically, and intellectually. This idea calls for a study of specific instances of conquest in the context of Rama’s encounters with Rakshasis (demonesses).

Rama, with the help of the sage Agastya, chooses the forest of Panchavati, beside the river Godavari as his dwelling to spend the years of his banishment. Valmiki describes the land where Rama enters as fertile and filled with pleasing flora and fauna:

Godavari’s limpid waters in her gloomy gorges strayed

Unseen rangers of the jungle nestled in the darksome shade!

‘Mark the woodlands,’ uttered Rama, ‘by the saint Agastya told

Panchavati’s lonesome forest with its blossoms red and gold,

…………………………………………………………..

Where the river leaves its margin with a soft and gentle kiss,

Where my sweet and soft-eyed Sita may repose in sylvan bliss,

Where the lawn is fresh and verdant and the kusa young and bright,

And the creeper yields her blossoms for our sacrificial rite.’ (83)

Soorpanakha, while wandering in her ‘verdant’ territory, spots Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana whom she identifies as strangers in her land. She is curious about their fair-skinned physical appearance, unlike her dark skin, and desires their complexion. Valmiki unfolds the social condition in which Soorpanakha as the ‘different’ un-Sita-like woman desires all that these strangers have, while they reject her for all that she is depicted to be: dark, big, and aggressive. After identifying Rama as the leader of the three, she immediately falls in love with him.

While Rama desires the beautiful land of the Rakshasa, Soorpanakha greatly desires him as a fair-skinned beauty. She accosts Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana:

And it so befell, a maiden, dweller of the darksome wood,

Led by wandering thought or fancy once before the cottage stood,

Soorpanakha, Rakshasa maiden, sister of the Rakshasa lord,

Came and looked with eager longing till her soul was passion

stirred. (89)

Soorpanakha is filled with desire for Rama, who is a ‘gentle husband,’ recounting the past to his ‘sweet and soft eyed’ wife. (89) At this juncture of Rama’s reminiscing, Valmiki inserts Soorpanakha into the story.

As developed later in the epic, a battle ensues with its inception inclaimstoterritorialrights.Drivenbyadesire,Soorpanakhalongs for Rama and rightfully questions his presence in her territory:

Who be thou in hermit’s vestments, in thy native beauty bright,

Friended by a youthful woman, armed with thy bow of might,

Who be thou in these lone regions where the Rakshasas hold

their sway,

Wherefore in a lonely cottage in this darksome jungle stay? (89)

Soorpanakha’s recurring question, ‘Who be thou?’ reveals her curiosity about Rama. The plot for the story of the battle of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ clearly has its inception in this sadly misplaced desire in Soorpanakha. Her attraction towards Rama tragically leads to her physical mutilation as punishment.

Soorpanakha accepts the settling of Rama and his family in her home, revealing a guilelessness that is evident in history where dominant communities settle into native territories and claim authority. Conquest is an accomplishment not necessarily by a superior power of the intruder, but rather because of the innocent welcoming by the natives as evident in the Christian colonial history including Native-American and Australian-Aborigine communities. Soorpanakha has no premade rationale to distrust the intruders and is immediately attracted to Rama, not knowing that she is lodged in his cultural judgment as the one to reject, humiliate, and punish. She does not attempt to chase away the new settlers from her habitat by harming them.

When Soorpanakha expresses her desire to marry Rama, both Rama and Lakshmana tease her as ignorant and humiliate her as an object of ridicule. Mockingly, Rama persuades Soorpanakha to turn her attractions towards Lakshmana as an eligible bachelor. Lakshmana continues to tease her: ‘I’m slave of royal Rama, woulds’t thou be a vassal’s bride?/Rather be his younger consort, banish Sita from his arms,/Spurning Sita’s faded beauty let him seek thy fresher charms’ (91). Lakshmana implores her to marry Rama and be his second wife. Soorpanakha is further agitated by this suggestion and threatens to slay Sita. Soorpanakha, who normally takes pride in her strength, is now a toy in the hands of these men and is angered by their ridicule and rejection: ‘Torn by anger strong as tempest thus her answer addrest:/‘Are these mocking accents uttered, Rama, to insult my flame,/Feasting on her faded beauty dost thou still revere thy dame?’’ (91). Rama considers the reactions of the Rakshasa savage: ‘‘Brother, we have acted wrongly, for with those of savage breed/Word in jest is courting danger,—this the penance of our deed’’ (92). Rama refers to Soorpanakha as the ‘savage breed,’ not capable of humor and therefore angered by ‘jest’ (Erndl 71).1 He interprets Soorpanakha’s anger as a lack of understanding his humor rather than a protest to his ridicule and rejection. The ‘chivalric’ love of Rama and Sita is divine and counters the ‘guileless desire’ of Soorpanakha for Rama which is ridiculed as ‘savage lust.’

Renouncing ‘Difference’ as Deviance

Kambar’s version of Ramayana known as Kamba Ramayanam in Tamil narrates the story of Soorpanakha adopting the human form of a beautiful maiden to appear in front of Rama (quotes are from the English translation by Rajagopalachari). This decision is undoubtedly based on an internalization that her body is undesirable:

So she stood there wondering, watching, unable to turn her eyes away. She thought, ‘My own form would fill him with disgust. I shall change my appearance and then approach him.’

She transformed herself into a beautiful young woman and appeared before him like the full moon. Her slender frame was like a golden creeper climbing the Kalpaka tree in heaven. Her lovely lips and teeth were matched by her fawn-like eyes.

Her gait was that of a peacock. Her anklets made music as she came near. Rama looked up and his eyes beheld this creature of ravishing beauty. She bowed low and touched his feet. Then she withdrew a little with modesty shading her eyes. (141)

In Kambar’s story, where Soorpanakha changes her form to suit Rama’s desires, she is aware of her inferior colour and stature in comparison with Rama. Kathleen Erndl, in her social-analytical commentary on the ‘The Mutilation of Soorpanakha’ (in Many Ramayanas), discerns: ‘The construction of Soorpanakha as ‘Other,’ as non-human, is particularly appropriate, since she really is other than human’ (71). Soorpanakha’s self-renunciation in exchange for another accepted image of attractiveness could reflect a tragic submission to standards of beauty, grace, and wisdom imposed by a dominant group. Soorpanakha affirms Rama’s supposition that she is a ‘female of the forest’ and that she is a Rakshasa. Valmiki describes the dominant social imaging of her as ‘poor in beauty and plain in face’ (91). In Kambar’s version, she is dark and big in contrast to fair and slender Sita, and hence Soorpanakha rejects her body and transforms into a body acceptable to Rama. When Rama wonders who she could be, public judgment controls her self-identity as she submits to his culturally informed, dominant iconography of definitions of beauty. Similarly, Hidimvà in the Mahabharata indulges in this process of transforming her image on seeing Bhima:

And on going there, she beheld the Pandavas asleep with their mother and the invincible Bhimasena sitting awake. And beholding Bhimasena unrivalled on earth for beauty like unto a vigorous Sala tree, the Rakshasa woman immediately fell in love with him, and she said to herself—this person of hue like heated gold and of mighty arms, of broad shoulders as the lion, and so resplendent, of neck marked with three lines like a conch-shell and eyes like lotus-petals is worthy of being my husband…. Thus saying, the Rakshasa woman capable of assuming any form at will, assumed an excellent human form and began to advance with slow steps towards Bhima of mighty arms. Decked with celestial ornaments, she advanced with smiles on her lips and a modest gait, addressing Bhima, said–O bull among men, whence hast thou come here and who art thou? … Who … is this lady of transcendent beauty sleeping so trustfully in these woods as if she were lying in her own chamber? … Ye beings of celestial beauty, I have been sent hither by that Rakshasa—my brother…. (Roy 312)

Having internalized the dominant conceptualization of beauty, Sister Hidimvà acknowledges her lack thereof and assumes the form of a human female to be desired by Bhima. Both Soorpanakha and Hidimvà masquerade and reject their natural body, transforming themselves into ‘desirable’ women.

Soorpanakha and Hidimvà attempt a reconciliation of desire through visible body renunciation. The writers present cultural perceptions which underlie the text, exposing the notion of the woman who is ‘different’ as treacherous, vulgar and threatening to the sanctity of the religious code of marriage. In Kambar’s version, Rama—on seeing Soorpanakha in human form—assumes that she is a ravishing visitor from some distant place. Ironically, he demands, ‘Which is your place? What is your name? Who are your kinsfolk?’ (141). She promptly establishes her identity: ‘I am the daughter of the grandson of Brahma. Kubera is a brother of mine. Another is Ravana, conqueror of Kailaasa. I am a maiden and my name is Kaamavalli [woman filled with lust]’ (141). While Soorpanakha takes pride in her family and her rights to the territory, she hides her true physical identity. She subordinates herself to Rama’s vision and perception of who she might be.

In the society that Valmiki describes, Soorpanakha stands in stark contrast with Rama and Sita:

[Soorpanakha]

Looked on Rama lion-chested, mighty-armed, lotus- eyed,

Stately as the jungle tusker, with his crown of tresses tied,

Looked on Rama lofty-fronted, with a royal visage graced,

Like Kandarpa young and lustrous, lotus-hued and lotus-faced!

What though she a Rakshasa maiden, poor in beauty plain in face,

Fell her glances passion-laden on the prince of peerless grace,

What though wild her eyes and tresses, and her accents

counseled fear,

Soft-eyed Rama fired her bosom, and his sweet voice thrilled

her ear.

……………………………………………………………..

Fawn-eyed Sita fell in terror as the Rakshasa rose to slay,

So beneath the flaming meteor sinks Rohini’s softer ray,

And like demon of destruction furious Surpa-nakha came,

Rama rose to stop the slaughter and protect the helpless dame. (91)

Such images of contrasts instate physical appearance as a determinant carrier of traits of wisdom, grace and power. The Rakshasas, depicted as dark with strongly built bodies, are stereotyped as demons with no right to gain respect and branded as lustful, threatening savages without mercy. Soorpanakha’s ‘wild eyes’ are filled with lust and anger as opposed to Sita’s ‘fawn eyes’ which are filled with fear, grace and devotion. Rama is ‘lotus-hued’ and ‘lotus-faced,’ while Soorpanakha is ‘poor in beauty, plain in face.’ She lacks character in her looks, and is de-faced and effaced in comparison with Rama. The process of Soorpanakha’s mutilation is well on its way before it is consummated because violence is initiated as an internalized process of mutilation of the self.

Roja Singh teaches interdisciplinary studies including Anthropology, Sociology and Women and Gender Studies at St. John Fisher College, Rochester, New York. Her ongoing research involves the oral narratives and leadership strategies of women from indigenous communities. She is president of the Dalit Solidarity Forum USA.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.