Supreme Court’s Exasperation Against Hate Speech is Tip of the Iceberg

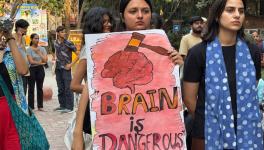

Image credit: The Leaflet

On Friday, a division bench of the Supreme Court directed police and other authorities, responsible for public order, to immediately and suo motu register cases against hate speech makers without waiting for a complaint to be filed. While the bench’s exasperation over the climate of hate prevailing in the country should hopefully have some effect, one wonders whether it is dealing with a mere symptom of a problem that runs much deeper.

The turn of the decade seems to have brought with it a monstrosity in the form of fake news. The issue has become further complicated with over-simplistic and reductionist views. The absence of consensus owing to the prevalence of several competing terminologies and definitions has allowed for easy percolation of the problem. While experts muddle over the theory, the behemoth roams freely, weakening the hold of democracy.

The internet revolution inspired new interpretations of the freedom of speech and expression; it has also begun to birth the insidious ability to alter, bend and mislead facts, and even culminate hatred and vengefulness. With the help of the internet, the public sphere has, in recent years, observed amplified citizen discourse. For a long time, the media facilitated this dialogue, as it does in any well-functioning democracy, but the public sphere has now become a breeding ground for misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and hate.

Without a doubt, these platforms have provided a stage for the underrepresented causes of minorities and enabled them to draw attention to their issues. In this sense, the internet and social media have acted as enablers of democracy. However, increased susceptibility to manipulations due to carefully designed algorithms which constantly feed one the agenda they identify with have begun to act as a roadblock in debates necessary in a democracy.

Interference with elections

Elections, which are conceived as the very foundation of modern democracy, were, according to Greek philosopher Socrates, lead to the rule of an unwise, corrupt mob. Greek philosopher Plato, in his book ‘Republic Part VI’, writes about the apprehension of Socrates about a populist democracy.

Socrates asks Plato’s brother, the ancient Athenian Greek Adeimantus to imagine a situation in which a sweet seller and a doctor are contesting elections as rivals. The sweet seller appeals to the people to vote for him by offering them treats. He also sways them against the doctor by pointing out how he gives them bitter potions. Sweet sellers or populist leaders often benefit from offering short-term benefits to an ill-informed citizenry. For this reason, Socrates warned against vesting voting powers in everyone, and suggested voting powers to rest with a select few.

While Socrates’ apprehensions are well-founded, they are not without resolve. A democracy, while seeming like a crystal duck, is not condemned to fall and break in every situation, if taken care of adequately.

One safety net comes in the form of the media. The media plays a huge role in ensuring that voting power can be safely vested in every single adult in a country by ensuring that citizens are ‘well-informed voters’ as against mere ‘voters’.

In a healthy democracy, the fourth pillar, which is the media, acts as a gatekeeper for free speech and a watchdog for democracy. However, of late, it has been observed that political interference in the media and the weaponisation of free speech by populist leaders to push their own agenda has stifled democracy. In a State where the government uses disinformation to engage with society, juxtaposed with a compromised media and limited pluralism, the society cannot, for long, resist its influence.

In fact, an estimation of the adverse impact a compromised media has on democracy can be had from former United States President Thomas Jefferson’s letter from Paris to American soldier and statesman Edward Carrington wherein he wrote “a government without newspaper or newspaper without a government, I should not hesitate to prefer the latter”, thus implying that self-governance is better than having a government with a compromised media in a democracy.

The Supreme Court in a recent judgment observed that the successful functioning of democracy can only be ensured through an informed citizenry. However, the informed decision-making process to cast votes faces challenges from information overload in this digital era. Social media, while facilitating free speech, paradoxically also threatens it as it interferes with open dialogue by cannonading users with inaccurate information, often protected under free speech.

Many established democracies like the U.S., Brazil and India are observing its effects in the form of weakening of democracy as election processes are compromised due to manipulation over social media.

The Supreme Court observed how polarised and less informed citizens have the tendency to believe unverified news and treat the information received from populist leaders as gospel. This undoubtedly interferes with the election process and destabilises democracies.

Populism to autocratisation

If American political theorist R.A. Dahl’s conception of democracy is our yardstick for a successful democracy, then of the seven necessary institutions he devised, four have been directly compromised by the weaponisation of free speech, and the remaining three have been impacted indirectly. In addition to the compromised election process, the right to free speech itself has suffered a great blow as it has been taken over by hate speech.

Even though all political systems recognise that free speech does not cover hate speech, in practice, it is difficult to draw a clear line between the two without risking impediments to free speech. Populist leaders benefit from these blurred lines as they masquerade hate speech as free speech, as observed in both India’s election of Narendra Modi and Donald J. Trump’s election in the U.S. Polish Member of the European Parliament Dominik Tarczyński, from the ultraconservative party Law and Justice, currently in power in Poland, has justified its anti-Muslim immigration policy by pointing out that that is what they promised in election campaigns and that is what the Polish people expect. Such an unapologetic attitude towards blatant racism is on the rise globally as populism in many countries is spiralling into autocratisation.

Ecuadorian-American academic Carlos de la Torre attributes the displacement of populism with authoritarianism to conditions where populists gain power in a state of political crisis and pre-existing weak democratic institutions. However, the example of India indicates that the pre-existence of these conditions is not a prerequisite if the fiction of a looming crisis can be created in the minds of the majority. This is often achieved by drowning out neutral media voices with heavy social media propaganda that relies on sensationalisation to gain viewers.

Democratic safeguards

Contemporary liberal democracies are facing threats from principles that protect them from turning into autocracies. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which protects free speech, amongst other rights, has been incorporated in most democracies.

Consider the U.S., which has one of the highest thresholds for violation of free speech. Most hate speech is protected and only criminalised if it ‘directly incites imminent violence’. This has resulted in the U.S. becoming an island of booming hate speech, not just for Americans but also to the peril of global democracies. Many people, seeking to create unrest and instability within a nation, utilise the liberal free speech spaces of America to fulfil their agenda. Neo-nazis from Europe evade anti-hate groups by finding sanctuary in American cyberspace. Since cyberspace is largely dominated by American platforms such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, it has become impossible for the world to isolate itself from hate speech and is thus witnessing a global rise in autocratisation as the internet permeates into more and more countries.

As lines between hate speech and free speech become blurred, it will become difficult for the public to differentiate between the reliable and the fake, thus seriously hampering public discourse and meaningful debate. The creation of information bubbles is already being witnessed as these social media platforms’ algorithms limit access to content from diverse sources and focus on providing targeted information. One person’s facts are another person’s fiction, thus compromising functional democracy.

As the power of hate speech is formalised by leaders around the world, it will become more difficult to resist resorting to hate speech, misinformation, and disinformation by populist leaders to pocket an easy win in elections, and at the same time keep up the charade of a democracy. The rise of this new ecosystem of unhindered free speech, facilitated by social media and exploited by populist leaders, poses a grave threat to the real idea of democracy.

While populist leaders may not be a threat unto themselves, when coalesced with compromised public discourse resulting in an uninformed citizenry, they result in what Socrates called demagoguery. Such a system also doesn’t resemble the democracy conceptualised by Dahl, which requires free and fair elections, free speech, universal suffrage, free access to alternative information, freedom to form and join autonomous organisations, government accountability, and responsiveness to voters. A populist democracy in such a scenario would more accurately be described as a ‘mobocracy’.

The sustenance of the current ecosystem is causing a gash to democracy with each passing day, and risks causing permanent damage to both journalism and free speech itself.

Shreya Bansal has an LL.M. in human rights law from Bristol University.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.