The Migrant Worker and the Goddess

Sculpted tableau of Durga and her children as a migrant worker family

Much ink has been spilt over this past week on this sculptural tableau of goddess Durga and her children as a migrant worker family. In the build-up to this year’s delayed Durga Puja, just as the image (then still being shaped in the sculptor’s studio) made its appearance on the first page of Kolkata’s newspapers, it went viral on social media. It created a new trend of a Durga Puja image becoming “an internet sensation”. This was fully in keeping with the times.

This year, as civil society, doctors and the Calcutta High Court came together to curb crowds and made all Puja pandals “no-entry” zones for spectators, the Pujas per force became a television and online viewing experience. So this Durga, like all others of the season, had her main life in virtual images. But none other quite stole the show like the creation by the Krishnanagar sculptor, Pallab Bhowmick, and “theme” artist, Rintu Das (of a migrant woman with her children), installed at the Barisha Club Puja in Behala, in the deep south-west of Kolkata. Endlessly circulated and forwarded by many who may never have toured the city’s Durga Pujas and seen its many forms of thematic installations, she invited a constant flow of opinions in online networks.

To begin with, there were debates about whether this figure of a migrant labour was herself the goddess, or whether the real goddess was the hanging animated image of Durga’s face, with her ten arms holding sacks of rice and grain. This ambiguity was deliberate, and central to the intention of the artist team. They talked about how they wanted this figure of a poor mother accompanied by her children to appear as if she was seeking food and relief from the goddess. But, in the process of her turning back to look at us, she herself takes on the third eye and the radiant face of Durga. Her impersonation is subtle, as are those of her children, marked out as a little Lakshmi, Saraswati and Kartik by their animal carriers (an owl, a duck and a peacock), whom they clutch under their arms like toys. It is the way each of them glance back, in a collective gesture, that makes for the key provocation of this sculpture. They seem to challenge us to fix their identity. We know that they represent the streams of displaced worker families, who, locked out of work and wage, were left with no options but to undertake the arduous journey homewards by foot.

These heart-breaking images that spilled into the media remained with the artist, Rintu Das, and gave him his choice of theme for this year’s Puja. We could think of their act of looking back at us as also marking the moment when the plight of this invisible workforce of our cities entered middle class conscience and became visible to the nation. That this mother and her children can also take on the persona of the divine family becomes part of the fluidity of identity that has been an essential part of the imagination of Bengal’s Durga. As Pallab Bhowmick and Rintu Das explained, their idea was two-fold: to accord the migrant worker family the grace and dignity it has always been denied; and to conceptualise the goddess group in the guise of a labouring mother and children seeking relief.

Jawed Habib advertisement

There is nothing new or out-of-form in this form of domestication of the goddess. Those who cried foul about the degradation of Durga’s iconography were swept aside as culturally ignorant. Anyone conversant with the many ways in which this divine pantheon in Bengal is continuously imagined as a part of contemporary human lives (as much of the middle class as of the less privileged) knows this to be a taken-for-granted representational license.

NRC cartoon in Uttarbanga Sambad

This is a license that animates the multiple worlds of artistic production, product advertising or political cartooning, where empathy can easily blend with humour and irreverence, without any sense of defilement of the goddess. It can be argued that Durga’s affective powers as an icon are neither neutralised nor deactivated, but recharged in her willing entanglements with the everyday worlds of human predicaments, on the one hand, and of consumptions and celebrations, on the other. So, she and her family can lend themselves with the same élan to new fashions and lifestyles as to the newest anxieties about the proof of citizenship. It seemed only natural that this year her iconography would be put to ready use to foreground the displacement of migrant labour that was brought on by the pandemic and the lockdown.

Snowcem Pujo Perfect Awards advertisement

But there have been other criticisms that have come up. Isn’t the worker-mother a tad too glamorous and sophisticated? Doesn’t “the perfection, finesse, and arresting beauty” of this sculpted figure take away from the harsh struggle of her real-life counterpart. (Sampurna Chakraborty, Facebook post, October 17, 2019). As the season arrives, every Bengali lady and girl child can take the liberty of becoming the goddess herself, and make her image gently morph into the face of the goddess. All that Pallab Bhowmick was doing was to give his figure of the migrant worker the same liberty and her own right to look poised and elegant.

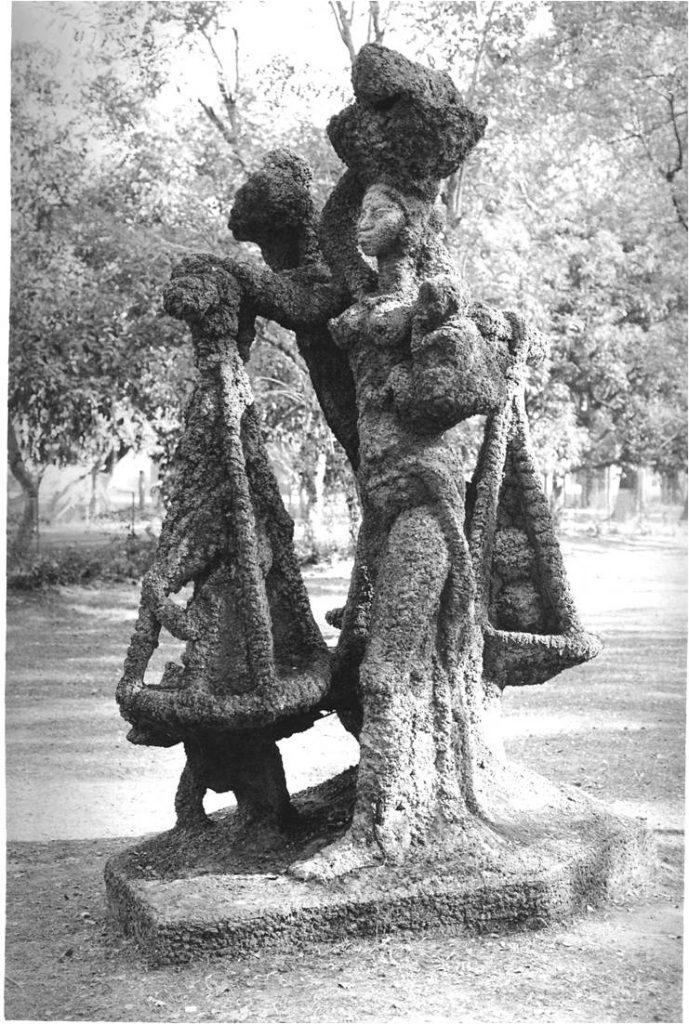

Ramkinkar Baij, Santhal Family, 1938, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

The figure’s provocation lies in her beauty, in her audacious aspiration to become something she can never be. There is something of a misjudgement at work, when this same commentator compares this work with the vigour of Ramkinkar Baij’s modernist cement and mortar sculptures of the Santhal Family or the Mill Call, to which this tableau can be seen to carry an implicit reference. Or when she echoes others in pointing out how this work directly plagiarises the painter Bikash Bhattacharya’s visualisations of Durga as Everywoman, especially his image of Durga looking back from within a crowd at a Puja pandal.

Bikash Bhattacharya’s work, Oil on canvas

If the Barisha Club tableau speaks of the art school training in academic realist sculpture of these little-known artists, it also announces their freedom to openly draw on the works of their far more renowned predecessors and introduce these in the realm of the public festival.

This is another representation license that is freely accorded to the contemporary art of the city’s Durga Pujas, without any charge of piracy or plagiarism. So, we have seen Ramkinkar Baij’s sculpture (a mix of the two above cited ones) appearing as a running Durga family group in a Dumdum Park Puja of 2007 in a Santhal village remake by Rupchand Kundu. Or a set of Ganesh Pyne paintings invoked in the puja of Abasarika Club in Dhakuria around the same time. There are many other such instances that can be cited. The point to underline is the way Durga Puja has, over the past two decades, opened up what we may call an “open-license” domain of public art production by small-time artists. The viewership it invites is quite different from that of the parallel circuits of contemporary art.

The field of the festival has thrown up its own array of creative livelihoods and its own dispensations of art and artists – ones that seek the equivalence of the more established worlds of modern art but enjoy none of the same rights and privileges. Neither the same authorial prerogatives over the created works nor the same assurance of their preservation are in place here. The life of these creations is as short and as seasonal as the festival itself. Even if this migrant worker tableau gets preserved, as has been promised by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, it will lose the aura that belongs strictly to its time and place in the festival. And it will soon recede from public memory.

Rupchand Kundu’s take on the Ramkinkar sculptures

To give the work its brief due, let me return to the extraordinary setting that was created around it, and capture the onsite experience of the installation in the darkened interiors of the Barisha Club.

On an unusually hushed Dashami evening, when traffic-free roads got me to Behala in record time, I pushed through the small crowd that had gathered at the barricaded enclosure and used my standing as a Durga Puja “author” (one that has never meant very much to Puja organisers) to negotiate permission and make my way inside. After all the hyperbole around the circulating image, I had gone prepared to be disappointed. Instead, I found myself awestruck.

The nature of the iconographic liberties taken by the two artists became sharper. Neither of the Durgas before us was complete, and neither could qualify as images for worship. In one case, there was no body to the goddess; in the other case, one of the children of Durga, the elephant-headed Ganesh, was missing. He appeared as the worshipped deity beneath the sculpture, sanctifying the ritual of the small ghat puja that was conducted at the site, as is often the case with many such ‘theme’ productions.

This liturgy of worship, however, was entirely incidental to the dimly lit, haunting ambience that was created of a relief camp for stranded workers. The title of the installation, “Traan” (meaning relief), was stamped on all the empty gunny sacks that were arranged in a layered semi-circle around the central figures. The material used was bamboo and jute cloth; the entire unit was monochromatic and devoid of any adornment or objects, barring these food sacks and a stray abandoned cart and bicycle.

The installation at the Barisha Club Puja

And the sounds kept playing of people scrambling and children crying with a voice commanding everyone to stand in order, saying “no mask, no relief”.

There is no mistaking the strong statement that was being put out. If there had to be a festival this year, it had to make room for social empathy and political protest; it had to carve out a place not just for celebration but also for a socially committed art practice. Like all the major Puja organising clubs, the Barisha Club too took pains to advertise its own relief work with migrant workers during the months of the draconian lockdown and drew attention to its greatly shrunken Puja budget this year. The artist, Rintu Das, made capital of this paucity of funds to make starkness and deprivation the theme of his production, putting to use the empty ration sacks that lay in the club room.

We know that for the lakhs of jobless, homeless workers, death from starvation was more imminent than death from the coronavirus. So, by replacing the weapons of the ten arms of the goddess with sacks of food, and by doing away with the figure of Mahishasura, hunger was rendered into the symbolic demon to be vanquished in this Barisha Club installation.

Kumartuli Sarbojanin Puja, 2020

One can keep debating about how genuine such gestures of empathy and compassion are. We can keep questioning the much-flaunted rhetoric of the Durga Pujas as a secular, socially inclusive festival that cuts across religion, class and caste. There are deep divides within that can never be papered over. (Somak Ghoshal, “Whose Durga is it anyway”, Mint Lounge, October 22, 2020). Yet, in a Puja season, where faces of destitution were everywhere, where the trudging migrant worker and the victims of the Amphan cyclone became the pervasive leitmotifs of festival pavilions, it is hard to dismiss these choices as only social tokenism or political eyewash.

Thakurpukur State Bank Park Puja, 2020

When the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP lobby in Bengal contends that the festival in this form is only about politics and not about religion, for once, they have hit the nail on the head. For, Durga Pujas in Bengal under the present political regime (Trinamool Congress) have become unabashedly political in a way they have never been before. And so has much of the festival art that thrives in its wake, charting a new aesthetics and politics of representation that is calling out for a different form of public engagement. If the Chief Minister has made this mega cultural festival of Bengal her prime platform of governance and political mobilisation, an expanding creed of local artists are also making optimum use of this festival as a space for public art, social activism and political critique.

It was no mere coincidence that the plight of the migrant worker exploded as a repeating theme in Puja pandals across Kolkata at the very juncture that the Central government made its scandalous declaration in Parliament about its “lack of data” about the number of workers who had perished and evaded all its responsibility and obligations.

It is pertinent to reflect on how the theme of displacement and impoverishment, more than the fear of the virus, offered a powerful handle of popular outreach for the ruling party in Bengal and all the big and small Puja clubs it patronises. The slogan of this year’s Cheta Agrani Club, the Puja of Mayor Firhad Hakim which has the strongest backing of the Chief Minister, was telling – “Ei bochhor, utsab noy, manusher pujo” (“This year, it is less a festival, more a Pujo for/of the people”).

By drawing attention to the loss of income and livelihood, this year’s scaled-down Durga Puja in Bengal was also made to confront the severe deprivations of the many in the state whose survival depends on this festival economy. From idol and pandal makers to artists and craftsmen, from priests and dhakis to those who set up street stalls, there were many who grievously lost out this season. In this critical pre-election year, Mamata Banerjee needed the full-blown extravaganza of the Durga Puja festivities more than ever to protect her turf. At the same time, the forced curtailment of the scale of the festivities was something she needed to take on board. The unabated rise in corona cases and deaths, leading to the High Court ban on public gatherings in pandals, came to her as both a challenge and an opportunity.

In a year, when the BJP organised on a lavish scale its first officially sponsored Durga Puja in Kolkata on the governmental premises of the Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre, going against the very ethos of a community festival, it was Mamata Banerjee and her loyal brigade of Puja organisers who held fort as the champions of a socially conscientious people’s festival. The face of the destitute workers came to stand in for the true, kindred face of this year’s Puja. And the sindur-smeared face of the migrant mother, who looks back at us with the face of the goddess, stood out as its most resonant emblem.

Tapati Guha-Thakurta is a Retired Professor of History from the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. She is the author of In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata, New Delhi: Primus, 2015. The views are personal.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.