Two-thirds of India far From Achieving Maternal Mortality SDG Target

Pippa Ranger/Department for International Development

While the Modi government appears to be content with the decline in maternal mortality rate (MMR) in India, the district-level picture reveals a challenging situation. In 448 districts out of 640, 70% of the districts in India; maternal mortality is still above the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) target of 70 maternal deaths per lakh live births.

In a first-ever district-wise study, Goli S, Puri P, Salve PS, Pallikadavath S, and James KS (2022) provide maternal mortality ratio for all states and districts of India. To date, India monitors maternal mortality in only 18 of its 36 states/UTs using information from the periodic sample registration system (SRS). There is no evidence on the district-level picture of maternal deaths. Using triangulation of routine records of maternal deaths under the Health Management Information System (HMIS), Census of India, and SRS, this study provides MMR for all states and districts of India.

This collaborative study by the International Institute for Population Sciences (India), University of Western Australia, and University of Portsmouth (United Kingdom) analysed 61,982,623 live births and 61,169 maternal deaths reported during 2017-20. HMIS enumerated numbers are considerably higher than the SRS sample of 429,173 live births and 525 maternal deaths at the all-India level during 2015–17.

At all India levels, SRS shows an MMR of 113 in 2016–18, while an HMIS-based estimate gives an MMR of 122 in 2017–19. According to SRS, only Assam shows an MMR of more than 200, but the study, based on HMIS, suggests that about six states (and two union territories) and 128 districts have MMR above 200.

AGGREGATE FIGURES HIDE GRIM SITUATION IN DISTRICTS

India accounts for 12% of world maternal deaths, second only to Nigeria (23%), as per the latest data available from WHO/UNICEF (2017).

In March 2022, the Special Bulletin on MMR released by the Registrar General of India showed a 10-point decline in MMR –from 113 in 2016-18 to 103 in 2017-19. The PIB release hailed that India is “on track to achieve the SDG target of 70/ lakh live births by 2030.”

The latest studyhighlights that “although MMR is falling at an average of 4.5% yearly, achieving the target set under Sustainable Development Goals-3 has to bring down the maternal mortality ratio at the annual rate of 5.5%.”

"We are behind the required rate to achieve the SDG target, and greater efforts are required. At present, the number of districts that might miss achieving the SDG target is quite high. This district-wise data will help in prioritisation of districts and planning and strategising accordingly,” says co-author Srinivas Goli, Faculty, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai.

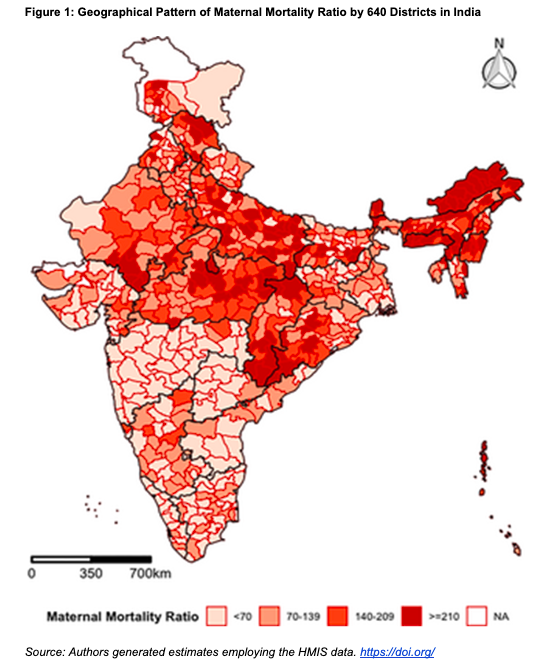

The findings from the study show the presence of spatial heterogeneity in MMR across districts in India. There is spatial clustering of high MMR in North-eastern, Eastern, and Central regions and low MMR in the Southern and Western regions. However, there are also huge within-state variations which include the better-off states.

A look at the MMR across districts shows a grim picture. Among the districts, the highest maternal mortality ratio is found in the Tirap district in Arunachal Pradesh, at 1671 deaths per lakh live births. Overall, 115 districts registered a maternal mortality ratio greater than or equal to 210; 125 districts show a range of 140-209; 210 districts fall in the range of 70-139, and only 190 districts reported a lower maternal mortality ratio than 70.

According to the study, seven out of eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states, the states which have high mortality indicators, including Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, still have a long way to go to achieve the target set under SDG 3. EAG states contribute approximately 75% of India’s total estimated maternal deaths, and Uttar Pradesh alone has more than 30% of the maternal deaths.

Taking India’s current average MMR (103) as the benchmark, Figure 2 gives a picture of how many districts in the top 10 states (in terms of the number of districts) have an MMR greater than this.

While in Rajasthan, 91% of districts have an MMR greater than or equal to 103, Assam, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh have 89%, 83% and 80% of districts, respectively, with MMR greater than or equal to 103.

FACTORS AFFECTING MMR

The study suggests that improvements in Antenatal Care (ANC), postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery, body mass index, maternal nutrition, years of schooling, and reduction of higher-order births, births in higher ages, and poor economic status will help in reducing MMR in the districts of India.

Also, districts with better health infrastructure have significantly less MMR, while those with a high SC/ST population show higher MMR levels.

One of the findings that come out in the study is that there is no significant negative association between institutional deliveries with MMR. This finding is corroborated by previous studies too. According to the study, "A considerable number of women rush to institutional deliveries when complications arise; most often, a majority of them have not obtained full and quality antenatal care. Thus, risky deliveries contribute to more deaths at the institutions compared to home deliveries."

“It must be ensured that incentives related to pregnancy must be given in instalments and not at the end of the delivery. It should be given throughout the delivery so that the intent to come to the facility increases. The Pradhan MantriMatruVandanaYojana does give the money in instalments, but we do not have the data to evaluate how good it is working. If full ANC is received, there are lesser chances of getting an obstetric emergency. People going for institutional deliveries without obtaining full ANC could be due to two reasons one is incentive attraction, and the other is a requirement of emergency obstetric care because of missing ANCs. This comes out in the case of Bihar, where institutional delivery is high, but the number of ANC is low," says Goli.

The study notes that despiteJanani Suraksha Yojana being in place, out-of-pocket expenditure on maternal health care in several states is way higher than incentives being given, which might be impacting accessing quality antenatal and institutional delivery care. From a policy perspective, it suggests that "The ongoing PMMVY must consider raising JSY incentives to ensure affordable and quality maternal health care for all.”

One disturbing finding of the study is that despite being a better-off state, Punjab records a medium to high MMR. In fact, both SRS and HMIS data reveal a rise in MMR over the years. The authors suggest that this could be due to unsafe sex-selective abortions leading to the death of women in the state, though a detailed examination of reasons for such a rise is needed.

Further, “the high maternal mortality in North-eastern states may be due to difficulty in reaching facilities in time, given the difficult terrain and less densely populated areas. The SRS data gives data for only Assam, but as our study analyses data from other North-eastern states, it reveals that MMR is high in other states of the region also,” explains Goli.

According to Goli, “SRS gives MMR only for 18 major states, and it is not brought out periodically. HMIS is like a census enumeration. Suppose there can be a method derived for estimating MMR using government-generated data like HMIS. In that case, it will be very advantageous as then it can be brought out more regularly and for all states and also districts. SRS estimates MMR from only 565 maternal deaths. We have analysed more than 60 thousand maternal deaths, with the completeness of registration reaching 80%. With a large number of samples, the error gets reduced. The government should use HMIS for estimating MMR, which is already being used in other assessments - SDG index, multi-dimensional index, monitoring the health status of different states and districts. HMIS is cost-effective and economical as data comes from the system itself. This can help in identifying the hotspots and prioritising them.”

It is sufficiently known that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the health services such as immunisation, ANC, and other essential services for pregnant women and children were adversely affected. Over this period, the mortality numbers would, thus, expectedly have gone up. What is required is that the government, with the help of this useful data and analysis, undertakes steps which help the situation at the district and sub-district level. Revelling in aggregate numbers will not help solve the problem.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.