‘Urdu Will Live on Until There is Love in This World’

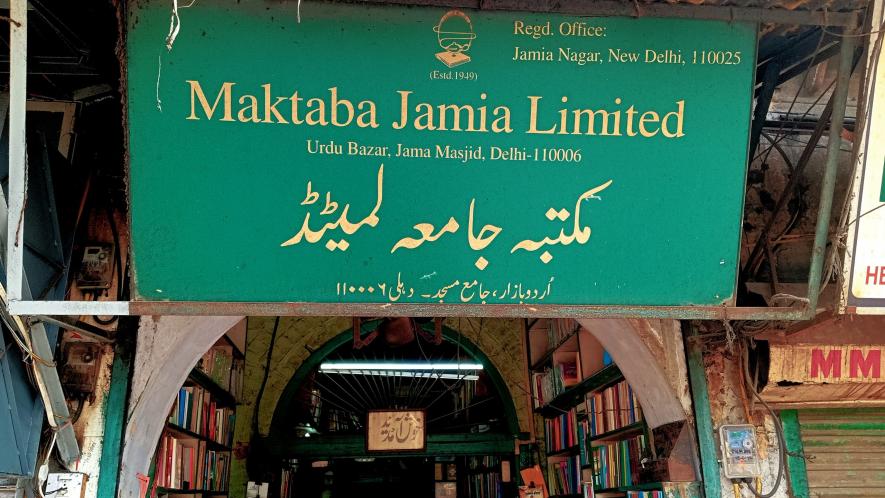

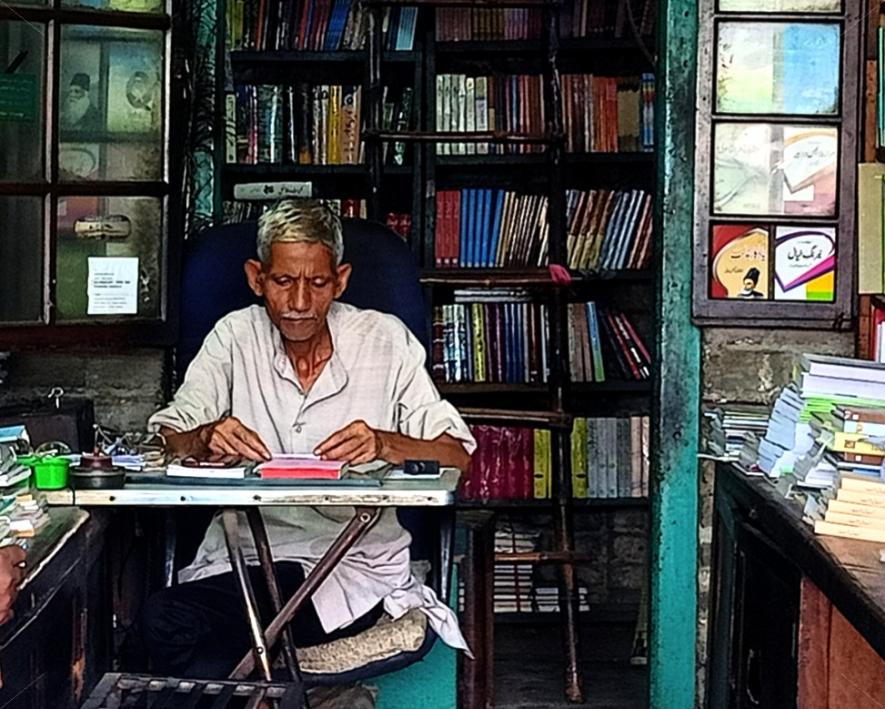

Right next to the magnificent Jama Masjid in Old Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar is one of the last reminders of the country’s lost glories, the Maktaba Jamia, a 74-year-old bookstore. This home to Urdu literary gems is housed in a location overshadowed by hotels, guest houses, restaurants, garment shops, makeshift stalls, and push-carts. And in their midst sits Ali Khusrow Zaidi, a living encyclopaedia of Urdu literature of the past half-century, and the bookseller-cum-manager of the Maktaba.

Like the language, the Sikandarabad, Uttar Pradesh, born Zaidi, has been a spectator of change since his youth. He arrived at the Urdu Bazar at 17 in 1971 and remembers the area as nothing but rows of bookstores for Urdu language and literature. Today, his eyes dart involuntarily towards the thronging crowds seeking out the kebab joints and the relentlessly flowing traffic. A few decades ago, most visitors to the area were book lovers and seekers.

“Bookstores and publishers were all you saw if you stood at Gate No. 2 of Jama Masjid. They covered the entire area,” recalls Zaidi. Nothing survives from that era except a couple of Urdu book dealers, such as the Kutubkhana Anjuman Taraqqi-e-Urdu and the Maktaba Jamia itself. “All others closed or preferred a more profitable business. A few were fortunate enough to shift their stores to better locations,” he says.

Indeed, most of the remaining Urdu bookstores deal solely in religious texts, but not the Maktaba, which has a wide variety of books and texts to interest people from every walk of life.

“Urdu Bazaar was known for its bookstores,” says Zaidi, rattling off their names from his long memory—the Kutubkhana Rasheedia, Kutubkhana Hameedia, Maktaba Burhan, Lajpat and Sons, Central Book Depot, Kutubkhana Nazeeria, Ilmi Kutubkhana, Chaman Book Depot, Saqi Book Depot, Deeni Book Depot, Maktaba Shahrah. “Now they are all a part of history,” he says.

Pointing at a kebab store nearby, he discusses the recent news of the Maktaba Jamia itself shutting shop. Within a day, a kebab counter was placed in front of the closed Maktaba, turning Zaidi’s worst nightmare into reality.

Zaidi started working at the Maktaba Jamia in 1978 and remained at its bookstore until retirement in 2014. He was later asked to return, which he did. Everything remained the same, except the year he was not paid his salary.

Months passed as he awaited his dues in one of the toughest moments of his life. His wife was seriously ill, and he needed the income for her treatment. He wrote multiple letters to the authorities, to no avail. “I even wrote to Prof. Najma Akhtar, Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia and the Chairperson of Maktaba Jamia, and attached my wife’s hospital bills and report, but I wasn’t fortunate enough to receive a response,” Zaidi recalls.

His payments were cleared a year later, but only after he released a public letter citing the issues at Maktaba, which the media reported. The episode made his position tenuous in the organisation, and, left with no other option, he handed over the keys to the bookstore this August. That is when the kebab store opened, right in front of the closed bookstore. Fortunately, there was huge opposition from the Urdu-reading people to this closure. As a result, Zaidi was asked to return to work. He agreed and the bookstore reopened within a couple of weeks.

“Maktaba Jamia was never just a workplace for me. It was a site of duty, a place to serve my language. It is an undeniable fact that the Maktaba Jamia has been one of the tallest figures in Urdu publishing and education. However, looking at its present condition, I have realised that Urdu suffers in the hands of its own people,” he says.

Having spent almost half a century working at Urdu Bazaar, Zaidi is sure that Urdu can never be painted in communal colours. “Urdu was never a religious language. Those who say it is a language of Muslims can be anything but literate. Who can remove the names of Mahendra Singh Bedi, Joginder Pal, Krishan Chander and Kumar Pashi? I have seen Hindus and Muslims in my bookstore, sitting for hours on its old benches, browsing its old wooden bookshelves shelves,” he says, while his eyes move from rack to rack.

“Women, children, students, professors, writers, poets, workers, and avid readers of literature, religion and region no bar, I have seen them all here. I see grown-ups come seeking books to learn the basics of Urdu and youngsters seeking literary works—and this is what Urdu Bazaar stands for,” he says.

Yet, Zaidi cannot deny how much the times have changed. The legacy of the once-thriving Urdu Bazaar is now in the hands of a couple of bookstores. “This lane has witnessed a serious plunge in the number of visitors searching for books. Some might think of it as Urdu’s decline, but I prefer a positive reason. I would like to believe that it is easier for people to find the books of their choice online.”

Indeed, Urdu Bazaar has become a living example of our lack of concern for heritage. The rapidly closing bookstores, publishing houses and institutions in this corner of the country prove we have treated our language as a ritual, not history and storehouse of our past. “We have failed to pass on a legacy that was passed on to us. But even if the last of these bookstores fails to survive, Urdu will continue to prosper. It will remain alive until there is love in this world. It is high time to take responsibility rather than passing on the blame,” he says, smiling as he turns to a customer looking for Masnavi Gulzaar-e-Naseem by Pandit Daya Shankar Naseem Lakhnavi.

The author is an independent journalist, researcher, theatre artist and a student of Preventive Conservation. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.