What Draupadi Murmu as President Could Mean for Tribals

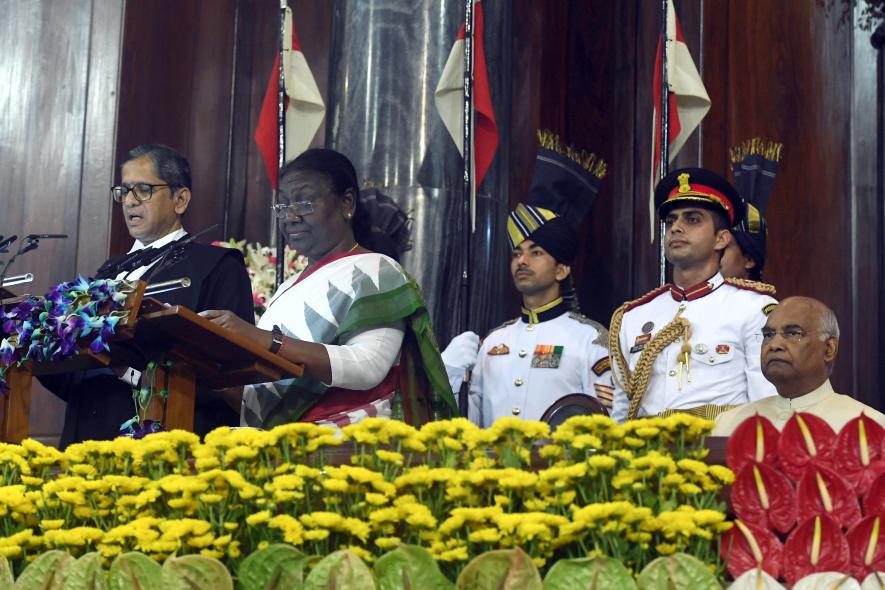

Chief Justice of India (CJI) Justice NV Ramana administers the oath of office to President Droupadi Murmu, as former President Ram Nath Kovind looks on, at the Central Hall of the Parliament. Image Courtesy: ANI

In Draupadi Murmu, India has got its first tribal president from the Santhal community, one of India’s Scheduled Tribes, constituting less than ten per cent of the population. Her election has a substantial symbolic value for the most marginalised community in India. The tumult in Indian democracy since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) mainstreamed Hindutva nationalism also makes Murmu’s election more significant.

Democratic Decline

Since 2014, civil liberties have been steadily eroded in India. Attacks on voices of resistance and social activists are a regular feature in news reports. There is a systematic social, economic and political assault on the Muslims and other marginalised sections as government agencies and state institutions are increasingly subservient to the ruling party and government. The BJP has centralised powers, deploying every public institution from schools to hospitals to push Hindutva nationalism.

Few refer to India as a thriving constitutional republic today. Instead, most independent observers say the country is trending toward authoritarianism. It is in this setting that Murmu has become the president, a position customarily perceived as crucial but limited in terms of powers.

Murmu’s victory needs a critical look from the perspective of whether it would aid and expand political Hindutva or rein in some of its worst tendencies. Indeed, her candidature by a conservative party inclined toward elite caste interests demonstrates how the BJP has restructured itself at the level of representation. Hindutva needs to co-opt marginalised identities and place them within the growing Hindu bloc it is creating. Indeed, without including subaltern identities, at least in the electoral realm, the BJP would have no hopes of becoming a hegemonic political entity.

When the non-elites join its fold, where the influential elite castes—its most loyal votaries—are already present, the BJP becomes an electorally dominant entity. Its rise in the Hindi heartland states was possible only when it aligned subalterns with elite Hindutva politics, creating communally-charged anti-Muslim politics. Of late, legislations—though carefully worded—have pushed this communitarian politics.

What would Murmu do when presented with an ‘anti-love jihad’ bill or a bill that seeks to alter citizenship along religious lines? These are questions only time will answer. Suffice to say that the success of Mandal parties in dominating politics in rural north India for nearly a decade required parties that represented ‘umbrella’ interests to rethink their strategies. This schism paved the way for the BJP’s ‘kamandal’ or religious-nationalism strategy.

Ultimately, Hindutva—now a 100-year-old force through the RSS—weakened regional outfits and caste-based identity politics. It could not have done this if it did not allow marginalised sections on its platforms. We learn from this that even if it amounts to symbolic inclusion, the subaltern wants a place in the political arena! Put another way, non-elite identities rose within the BJP as part of its ideological outreach. For this reason, many would see Murmu’s rise from the same prism: as a serious step towards accommodating tribals in the Hindutva fold.

Indeed, identity and representation are evergreen questions in Indian politics. Words such as samman (dignity), sashaktikaran (to empower) and netritva (leadership) are constantly bandied about by parties across the political spectrum. Now that Murmu has won the presidential election, the BJP is linking tribal elevation with 75 years of freedom. But this would be a stretch considering the actual position of tribals in India’s politics, society and economy.

Why parties opposed to the BJP failed to challenge the admittedly hefty symbolism of a tribal woman as president raises questions about how inclusive they are. Non-elite socio-political assertions have spurted across India, but ironically, conservative and orthodox BJP set the example for representation.

Electoral incentive

In the coming days, the BJP will surely claim that Hindutva accommodates tribals within its fold and represents their aspirations. Murmu, from Mayurbhanj in Odisha, was earlier the first woman Governor of Jharkhand. The BJP perhaps hopes she will impress the tribals to support the BJP electorally in the state. However, electoral incentives in tribal areas remain in doubt. North India’s sizeable tribal population has resoundingly rejected the BJP in recent electoral contests. In Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh Odisha, and in Madhya Pradesh, where the BJP gained power after defections in the ruling Congress, tribal voters form upwards of 20% of the population, but did not give it a chance to return or rise to power.

One reason could be that while hegemonic Hindutva allows tactical representation of marginalised identities, its Hinduisation project denies tribals their distinctive identity. For example, the BJP and RSS avoid using the term Adivasi, or original inhabitants and instead use Vanvasi or those living in forests. The electoral successes of the BJP depend on creating a permanent ‘Hindu’ voting block, also because it has no substantive plan to empower or uplift the tribal communities. This fundamental flaw is why many would judge the representation of the marginalised in the BJP fold as symbolic and devoid of concrete political, social and economic programmes for equity.

Independent President’s Office

Will Murmu will stand tall against the authoritarian tendency of the BJP? Will she bring positive changes to the life of the Indian republic? As Governor, she refused to pass specific bills that hurt tribal interests and consented to some such legislations. Will she recognise that tribals face the wrath of the Indian state and systematic assault through the dilution of laws that safeguard their interests? It is impossible to predict this. However, it is known that the BJP straightforwardly serves neo-liberal capitalist interests. Therefore, corporate miners await the dilution of forest laws that limit their access to Adivasi forests. And often, BJP-ruled (though others too) have sidelined the protective PESA Act. Tribal rights activists are lodged in prisons on frivolous charges under stringent regulations.

So will President Murmu autonomously serve Adivasi interests? To assume either way is futile, but we have enough evidence of centrifugal forces that dictate decision-making during the present regime. The regime seeks to pursue Hindutva, promote a dissent-free society and pursue neo-liberal reform. So far, the constitutional figures it has picked have not drawn its ire on these fronts. However, any constitutional figure who seeks a struggle on these fronts would find one ready.

The author is a researcher and political commentator. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.