Who Cares About a Couple of Iraqis Anyway

Image Courtesy : NewYork Times

I

The New York Times has been in the eye of the storm after it published a report “The ISIS Files” by Rukmini Callimachi. Over the course of five trips, Callimachi and her team collected as many as 15,000 pages of documents. In addition to the story, Callimachi has also started a podcast on the New York Times, called “Caliphate”.

Screenshot of the New York Times story

Callimachi’s aim was to uncover the day-to-day workings of the Islamic “State”. She asks, “...what the militants left behind helps answer the troubling question of their longevity: How did a group whose spectacles of violence galvanised the world against it hold onto so much land for so long?”, and answers, “Part of the answer can be found in more than 15,000 pages of internal Islamic State documents I recovered during five trips to Iraq over more than a year.”

The documents reveal a picture of quotidian life in Iraq controlled by ISIS. A majority of the documents shows how the ISIS bureaucracy worked: they are marriage contracts, legal proceedings, manuals on how to dress, and other aspects of daily life. These facts show that ISIS, which was far away from international recognition as a state, thought of itself as a state. A Vice News documentary inside ISIS-controlled Syria and Iraq, published on August 14, 2014, also shows how the members of the ISIS manned streets, checking men’s and women’s garments, ensuring liquor shops are closed. The man manning the operation on the street tells the Vice News correspondent, “We are a state.” In an interview with Lisa Ryan for The Cut, Callimachi says, “We’re in the habit of saying theirs was a ‘so-called state’, but I think that’s wrong. The documents show that they had a functioning state that was not recognised by anyone else. They had an administration that in some ways outperformed the government they usurped. They had every department you could imagine, from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Sanitation, an HR wing, a medical department.”

Although the risks involved in completing such a task as Callimachi’s are immense, especially when ISIS is known to be intolerant towards journalists, the article has given rise to an outcry following the manner in which the documents were collected, translated, and published.

Sarah Farhan, a Ph D student at Toronto’s York University, working on the Royal Medical College of Baghdad, emailed Callimachi if she got the consent of the Iraqi authorities before procuring the documents, but received no reply, reports Maryan Saleh of The Intercept. Then, she launched a petition that asked the New York Times’ editors to rethink their use of the documents. The second point of the petition says, “That the removal of these files from Iraq is in violation of international law, in particular the prohibition of pillage under the 1907 Hague Convention, the protection of cultural heritage under the 1943 London Declaration and the 1954 Hague Convention. This principle of the protection of cultural heritage, including the prohibition of the transfer of such items, has been affirmed by the UN Security Council Resolution 1483 (2003), adopted under the shadow of the disgraceful looting of Iraqi National Museum and the National Library.”

There is still some confusion if these regulations apply to non-state actors like journalists, as Bruce P Montgomery argues with respect to the controversy surrounding archives concerning the Iraqi Memory Foundation about which we will read more. These legal questions become even more complicated when the documents are related to ISIS, which is not a recognised sovereign state.

Judith E. Tucker, the president of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) and professor at Georgetown University, and Laurie A. Brand, chair of the MESA Committee on Academic Freedom and professor at the University of Southern California, however, has published an open letter to Callimachi and the editors of The New York Times, reprimanding them for publishing the story. Their demands? “We call upon both Ms. Callimachi and your newspaper, which has no right to possess or retain these materials, to immediately return all of them to the proper Iraqi authorities in their original form. In the meantime, neither Ms. Callimachi nor anyone else should be permitted to make public any documents containing personal information, as the 4 April article did and as Ms. Callimachi has done in a subsequent series of tweets, because such disclosures potentially endanger the lives of individual Iraqis.”

Screenshot of the statement

Irrespective of whether Callimachi and The New York Times have the legal authority to collect the documents, the publication of the story has only widened the mistrust between the American media and Iraqis, or scholars who work on Iraq. Sara Farhan’s tweet to Callimachi, “You are a thief and a disgrace,” reveals the extent of this breach of trust.

Edna Fernandes, author of a book on ISIS, The Hollow Kingdom, who hasn’t visited Iraq or Syria, but did conduct several interviews with former ISIS supporters, and other Muslim clerics running Deobandi madrassas in Britain and India, said in an email interview, “As a writer and a journalist I think it is vital to carry your work out with openness and honesty, whenever possible. Of course, there are scenarios where journalists work undercover. When it is to uncover material that is in the public interest, I believe working undercover is very much justified. The finest journalism is sometimes conducted in the shadows out of necessity, especially where the work is dangerous.”

“My approach has always been to declare my name, organisation and interest, whenever possible. In writing all of my books I have been up front about who I am and why I am doing it. I prefer to have information on the record and through first hand accounts. Certainly, while carrying out research for Holy Warriors (another book on religious fundamentalism in India) and then The Hollow Kingdom on madrassa education in both the UK and at Deoband in India, I declared I was a writer and journalist and asked for permission to come in and interview people. I did my interviews on the record with written notes and with no hidden cameras or recordings. If I ever used a recording device, it was done so openly and with the permission of the party concerned.”

“Why do I think this is important: I believe in order to elucidate understanding, there has to be trust. Questions can be hard hitting but framed in a polite way. Then you dig deeper with more questions. It is important to go in with research preparation done but with an open mind. I do not go in pre-writing my ‘story’ as this undermines the whole purpose of the interview which is insight and understanding. In the cases of Deoband and the madrassa in the UK that I was invited into, it took months to persuade the people concerned to open their doors. In the case of Deoband, I was the first woman to be given permission to stay at the madrassa for almost a week. When interviewing adults, I used their full names and quoted what they said ‘on the record’. Also, when interviewing children, I sought to protect their identity by only giving first names or another name where revealing their identity may put them at risk of violence.”

Cover of Edna Fernandes’ book/ Image courtesy Speaking Tiiger Books

These practices, however, have an end result: towards maintaining and emboldening trust between the reporter and the reported. “In the end I am aiming for writing that provides insight and understanding, rather than provoking division and mistrust,” she says. “If we are to understand and as a society address the complexities of religious division and even terrorism, we have to begin by trying to listen to ordinary voices involved. The failure to listen and understand has only inflamed divisions and led to failings in the West as it tries to get to grips with the sources of grievances in the Muslim world.”

II

This is not the first time that questions around archives has been raised with respect to Iraq and its recent history. These questions arose when the Iraqi Memory Foundation (IMF), based in the US and founded in 1992 by Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi American professor of Middle Eastern studies at Brandeis University, acquired extensive archives of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party. A private organisation, the IMF is an extension of the Iraq Research and Documentation Project at the Center of Middle East Studies at Harvard University.

The estimated size of the archive varies. One article in Stanford claims it is 7 million archives while another says it contains “10 million digitised page images and 1,500 video files collected from Iraq’s Ba’ath headquarters and other sources”. In 2008, Makiya signed a deposit agreement with the Hoover institution at Stanford University for the upkeep of the archives. This, however, happened only after the archives exchanged several hands: after being kept in Makiya’s parents’ home in Baghdad’s Green Zone, they fell into the hands of the US Army, who scanned the documents and handed them back to Makiya in the United States. An article by Clifton B. Parker written as recently as March 29, 2018, reveals the politics behind this collection. They are cited every time a commentator validates the Bush administration’s war of Iraq. The sub heading of Parker’s article, for instance, says, “A comprehensive archive documenting Saddam Hussein’s rule reveals the inner workings of brutal authoritarian rule, and it is helping both scholars and government representatives better understand the full scope of the coercive measures the regime used.”

Makiya’s access to the archves in the first place was achieved through political clout. Known to be an active supporter of the US-Iraq war, he was in Iraq when an US lieutenant found files at a regional headquarter of the Ba’ath party in Baghdad, and inquired of their worth from him. Makiya said that he had permission from the US authorities to remove the files from the location and work on their upkeep. Several commentators (Gorlick, “Grim Treasure.”) have argued that neither Makiya, nor the US authorities whose permission he cites, had any authority to decide the fate of these documents.

Saad Bashir Eskander, the director of the Iraq National Library and Archives (INLA) has asked for the documents to be returned to Iraq because they are the property of the Iraqi people and is part of their collective memory.

The irony of these arguments is not lost on anyone when one realises that the largest collection of the Ba’ath-era documents does not lie with the Hoover Institution, but with the U S Department of Defense. (This claim has been made by John Gravois in “Disputed Iraqi Records Find a Home at the Hoover Institution,” published in Chronicle of Higher Education 54, no. 21 (2008): A1–9).

The history of the Ba’ath Party archives gives us a more recent history in which Iraqis feel that they have not been given access to their archives, and in turn, the chance to write their own history, but there is a story to this. Historian Arbella Bet-Shlimon, who teaches at the University of Washington, for instance, reflects on the larger questions of archives originally belonging the Middle East in his essay “Preservation or Plunder? The ISIS Files and a History of Heritage Removal in Iraq”:

Westerners began to remove historical artifacts from Iraq in the nineteenth century. At the time, archaeology was ascendant as a discipline, and scientific knowledge production was intertwined with the project of imperialism. In addition, Mesopotamia figured prominently in biblically inspired notions of European heritage. The British and French archaeologists who collected items such as cuneiform tablets and sculptures therefore felt they had a greater affinity to them than did the mostly Muslim local inhabitants. After all, the locals had left them undisturbed and were, in this European view, apathetic to their existence.

The first national institution in modern Iraq devoted to collecting and studying historical artifacts was established in 1922, when Iraq was a League of Nations mandate territory under British administration. It became known as the Baghdad Antiquities Museum in 1926 and was later renamed the National Museum of Iraq. The museum’s founder, Gertrude Bell, was a British archaeologist turned colonial official who put herself in charge of deciding which archaeological findings would be kept in Iraq and which could be sent back to Europe.

When Sarah Farhan, working on the Royal Medical College of Baghdad, laughs and tells Maryam Saleh of the Intercept, “I would’ve graduated two years ago,” referring to how she would have fared had she had an easier access to archives on the Medical College, we must recognise that there is a long history of cultural pillage she is referring to.

III

This recent history of the dispute over the Ba’ath archives is a good context to understand the anger over Callimachi’s story. As Fernandes says, “In her defence, she may have felt that leaving this original evidence behind risked it being destroyed. But the key issue here is these documents are evidence of war crimes and atrocities perpetrated by ISIS in Iraq. If there is to be any healing in the country, it is evidence such as these that will help bring the guilty to justice. When journalists are given original documents, they are usually copied and returned to the source. The documents do not belong to us.

In the case of the New York Times’ files, the document cache may have been too large to view and copy safely and quickly in a volatile conflict zone. It is a morally grey area to remove original documents that are evidence of war crimes. Perhaps, they should have been taken to a safe place in Iraq, copied, and returned to the Iraqi government or to a recognised agency such as the United Nations. But we have to remember the New York Times has a great tradition of using leaked documents in a responsible way for the greater good.”

In an answer to Michael D Miler’s question posed in the “Readers Interactive” section on the New York Times website, on how the New York Times can be certain that the intelligence it has gathered will be shared, Callimach responded by saying, “We are also working to find partners to make the entire trove digitally available. Once that happens, anyone — civilians in Mosul as well as intelligence analysts — will be able to see the material for themselves.” Does making the archive available digitally solve the concerns several people have raised? Rochelle Pinto, who has co-authored a monograph Archives and Access for the Centre for Internet and Society, based in India, but who did not claim expertise on the legal aspect of digitisation of archives, offered to make a point about the ethics of this practice. In an email interview she said, “The same question – what authority do journalists have to remove documents – holds for the decision to digitise them and make them public. The question of rights and of ethical handling of such situations arose with Wikileaks as well, though, in this case, the violation of the rights of Iraqis is stark. In both cases, the judicial handling and pre-processing of information would take a lot of time and effort, but would have helped establish conventions for the future.” Pinto is not the only person to draw a comparison with Wikileaks. Sean Lee, a PhD candidate in political science at Northwestern University, and a research affiliate at the Center for Middle East Studies at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, asked Callimachi, “What possible journalistic value comes from not redacting the names of normal Iraqis in these documents? Has it not occurred to you that you could be putting their lives in danger? Ms. Callimachi claims that redacting people's names is tantamount to censorship, yet The Times redacts information all of the time in documents that it releases. The WikiLeaks documents are a perfect example, where the names of buildings under U.S. surveillance in Iraq were redacted. Is it the position of The Times that protecting something like U.S. surveillance operations in Iraq is really more valuable than protecting the identity of normal Iraqis?”

Most of the anger towards Callimachi has resulted from her lack of concern for the ordinary Iraqi citizens, whose ordinary day-to-day lives under ISIS she is so determined to uncover.

Safety and security should and are prime concerns in conflict zones. Callimachi, in an interview with The Cut, in fact, lauds the way in which the New York Times keeps the safety of reporters in mind: “I’m lucky that I work at the New York Times because they have very thorough protocol for sending reporters into these areas. We don’t just show up somewhere; there’s an entire security plan and there are a lot of levels of approval that you go through before you go anywhere. That of course gives you some reassurance.” It is also not too far-fetched to assume that the New York Times receives the help that a superpower like the USA and its allies have to get the first access to documents of the kind that Callimachi has recovered. Just as there has been a running theme of the brave journalist who risked her life to write about ISIS, there has to be an equal concern for the Iraqis who’ve lived under ISIS, and whose lives the brave journalist wants to write about.

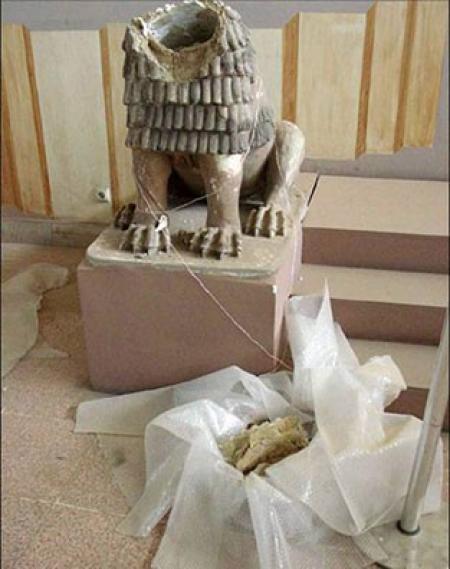

Besides, the rut goes deeper than questions of cultural appropriations of Iraqi archives by the American media. Journalists like Vijay Prashad and Mehdi Hasan have argued that it was the US invasion of Iraq that propelled the formation of ISIS. One of the fallouts of the US war on Iraq was also the looting of the Iraq Museum. Although controversy over who must be blamed for the looting remains, it is not too far-fetched to say that avoiding the war would have also meant averting the disaster of losing the surviving remnants that tell mankind the history of its civilisation.

This life-sized terracotta lion statue was one of the many artifacts in the Iraq national museum that was damaged during the April 2003 looting. This lion originally guarded the main doorway of a temple at Tell Harmal during the old Babylonian period circa 1800 BC. Photo credit Joanne Farchakh-Bajjaly May 2003. Image courtesy:The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago

The Warka vase, a masterpiece of early Mesopotamian art, was stolen during the looting of the museum and was returned damaged two months later. When looters stole the Warka vase, they broke the main body of the vase away from its display case leaving the modern plaster vase. Photo credit: John Russel May 2003/ / Image courtesy The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago

Besides, a contradictory US foreign policy that, on one hand, allies with Saudi Arabia, and claims to fight ISIS on the other, helped in the growth of ISIS. This is not just a critique made by critics of the US. It was a dilemma even for John Kerry, as a leaked audio tape shows. Fernandes has a simile for Saudi Arabia in her book The Hollow Kingdom. She writes, “Saudi Arabia is the victim of Wahhabi inspired terrorism and ally of the West in the war on terrorism at the same time as it is the exporter of Wahhabi doctrine that inspires the terrorists. And thus the world is caught in a cycle of terror. Saudi Arabia is like the man who hurls the Molotov cocktail at a building and watches it explode, then rushes in to douse the flames.”

IV

Callimachi’s is also not the first time an effort has been made by the media to understand the day-to-day life under ISIS. In December 2014, the BBC published “Mosul diaries: Poisoned by Water”, a series of diary entries written by ordinary Iraqis describing life under ISIS. Fernandes quotes from these diaries extensively in her book. She says, “I relied on brave people within Iraq who spoke out or who risked their own lives to publish material on life under ISIS online or through regional agencies. If the sources are reliable, there is nothing wrong with that. Nor is there anything wrong with using copies of credible Iraqi documents that expose the truth about ISIS.”

“The terrorists portrayed it as a "Caliphate" and exhorted Muslims to come from around the world to build their state, to bring children and extended families. Yet their portrayal of life under ISIS was a lie. It was brutal, venal, corrupt and cruel, which is why I called my book The Hollow Kingdom.”

“The diaries showed a glimmer of truth about everyday life and clearly illustrated that those forced to live under their rule did so under duress and in fear. Ordinary voices are more telling in their detail than the grand analysis of experts.”

In her book, Fernandes explains that the ISIS economy worked by pillaging and selling many artefacts belonging to Iraq and Syria. ISIS relied on local sources who could tell them the worth of historical monuments. Then they would then sell them in the black market. Non-cooperation by local historians would result in murder. In the course of the email interview, Fernandes said, “Iraq is a country that has seen its cultural heritage raped by the terrorists and their middle men. Its cultural treasures and history has been destroyed, ripped out and sold to the highest bidder to finance ISIS' terrorist kingdom. Now that ISIS in Iraq is defeated, there is anger about an American journalist taking original documents and evidence out of the country for her story.”

There seems to be no immediate end to this fiasco, but the greater ethical need to allow Iraqis write their own history can best understood through Saad Eskander, the director general of the Iraqi National Library and Archives’ final words in a 2008 open letter to the director of Hoover Institute:

The Ba'ath documents are the property of the Iraqis and the institutions that represent them, and so it is arrogant and unethical for one person (an émigré) to decide the destiny of millions of sensitive official documents that have had and will continue to have considerable impact on the private lives of millions of Iraqi citizens. It is not in the interests of Iraqi victims and academic investigation for the IMF to have been using the documents for propaganda, self-aggrandizement and obtaining funding. The Iraqis desperately want to know and confront the realities of their recent past. They need to recognize the suffering of the victims and to identify those who committed crimes, before bringing them to justice. The Iraqis are well aware that any national reconciliation project cannot be successfully implemented without making the seized documents available for both scholars and the public mediated by a responsible agency representative of them.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.