Why this Government Does Nothing About Economic Crisis

The current political dispensation came to power on a promise of rapid economic growth combined with undeclared assurances of cultural majoritarianism. During the election campaign for the 2014 national elections, it projected the “Gujarat Model” as a “success story” for having achieved the right combination of high growth and a polarised society. Whatever the veracity of that claim in an industrialised society like Gujarat, the model was sought to be replicated in the rest of India.

However, we find under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah’s leadership, that cultural majoritarianism is taking over the imperatives of both economic growth and development. India has moved from the promise of “acchey din”, or good times, which in economic terms implies greater employment, better and more housing, and further chances at mobility, to a situation that some have lately referred to as an economic emergency.

The economic situation can be seen as a trade-off, or a crisis created by a global slowdown, but the more important question is if unabashed cultural majoritarianism can co-exist with greater economic growth and inclusive development. Is it possible that the core strategies integral to majoritarianism are at cross purposes with the social conditions that are necessary for growth and development? Could one, therefore, argue that the current economic crisis is not an aberration or the result of a global economic slowdown, but a necessary feature of the politics of cultural majoritarianism?

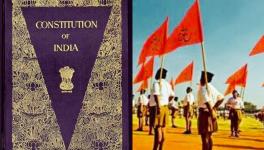

Cultural majoritarianism, or the project of building a Hindu rashtra, is a commitment born out of a long-term political and social vision of the current dispensation under the influence of the RSS or Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Its commitment to this cause is hard-nosed and does not balk at the pros and cons of its implementation.

Recent decisions of the government to abrogate the benefits of special status granted under Article 370 to Kashmir, to build a temple dedicated to the Hindu god Rama, criminalise the practice of instant triple talaq, create a National Register of Indian Citizens or NRIC and clear the Citizenship Amendment Act or CAA 2019, have been in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s manifestos for a very long time.

With their absolute majority in Parliament, it looks highly unlikely that anything, including the effect of their decisions on the economy, will force a rethink or make the present regime dither. It is important to investigate how the ideas of exclusion, hierarchy, fear, violence, undermining the autonomy of institutions, speculation, and doubtful information converge or diverge from the imperatives of growth and development.

In India cultural majoritarianism, to a large extent, represents a popular will that has been arduously constructed by right wing mobilisation since the colonial times. It faces a dual pressure: to represent the popular will and perpetuate a mood of retributive exclusion and assertion by the majority community. Despite this long-term vision of their political project, the immediate strategies of mobilisation required to sustain majoritarian will are based on galvanising emotions and building perceptions of victimhood and insecurity. These require immediate and knee-jerk responses that can produce a sense of immediate gratification.

The economy, on the contrary, requires a more sustained policy frame, institutional coordination and data as well as technical expertise. It requires a social condition conducive to investment and an efficient institutional functioning based on reliable data and information. Majoritarianism, which is built on perceptions and images, is at odds with transparency.

The recent comments of the industrialist Rahul Bajaj that fear is the dominant mood in the nation are a symptom of the impact majoritarian political mobilisation has on the economy. What happened to Karvy after the public statement is open to speculation. Similarly, recent controversies over fudged growth data also affirms the dispensation’s inability to do a course correction. That would affect the larger-than-life image of its leader. Instead, it has to compulsively make claims of the infallibility of the leader and his decisions.

Majoritarianism necessarily imagines a unified ‘people’ held together by virtue of common memory, history, culture and language. It is compulsively dependent on mobilisations around issues, which are projected as common to “the people”. To this end, the projection of a strong leader, corruption—an issue which affects all sections of society—and the temple as a common symbol of the majority population are necessary conduits. Meanwhile, by definition, the economy requires identification of the social and economic differences between various sections of society, including their class location, rural-urban distinctions, differential incomes, and so on.

The neo-liberal model of growth initially found the ultra-nationalism of the BJP-RSS combine favourable for its ability to ‘overcome’ and submerge social and economic differences and replace it with an ideal of cultural unity. It is this idea of unity that offered a possible basis to foster the image of a ‘reformer’ Narendra Modi, who would introduce changes conducive to faster accumulation of capital and growth, both in a way that helped the corporate sector.

This is unlike during the Congress regime, whose loose organisational structure and weak leadership proved incapable of pushing hardcore reforms and often accommodated public pressure and thus moved away from neo-liberal reform—apart from being seen as vulnerable to corruption. In the majoritarian model of leadership, politics finds it difficult to respond to public pressure: giving way is seen more as succumbing or capitulating than as a legitimate practice in a democracy.

While the BJP-RSS combine draw their essential legitimacy from their cultural majoritarian agenda, the Congress party drew it from its social democratic character. Social welfarism was, therefore, a necessary part of Congress maintaining its popular appeal. The BJP feels no such compulsion. For instance, the current economic impasse is being visualised by many as more of a demand side crisis than that of the supply side. Yet the current regime refuses to pump more money into the hands of the people but prefers to offer more tax relief to the corporate.

Social spending by the government is an important aspect of demand-side management of the economy. It lifts the misery of the working poor, puts some resources in their households and gives them, to varying degrees, a relatively greater freedom of choice about spatial mobility and employment. Access to these choices of mobility and employment, it is found, are also a kind of protest against forms of exploitation, exclusion, the stigma associated with particular activities considered filthy/impure, especially in the rural hinterlands, and against caste discrimination. Inclusive development has underlying links with protest and it is an acknowledgment of diversity, which is anathema to the current political dispensation. It would, therefore, be instructive to wait and watch how cultural majoritarianism would continue to speak to the economically marginalised groups in the course of the remaining tenure of the current regime.

Ajay Gudavarthy is associate professor, Centre for Political Studies, JNU and G Vijay is assistant professor, School of Economics, University of Hyderabad. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.