Why India Must Recall 1961 Madhya Pradesh Communal Violence Today

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: PTI

During the election campaign for the Madhya Pradesh Assembly, leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is ruling in the state and at the Centre, repeatedly raised religious issues, especially the temple dedicated to Lord Rama under construction in Ayodhya. Even Union Home Minister Amit Shah raised the temple issue during the campaign. The temple and religious issues were presented with a clear intent to appeal to the electorate on communal lines.

Recall that in the recent past, Madhya Pradesh has witnessed communitarian polarisation like never before. The forces that target minorities, such as by using bulldozers to demolish their homes or those of the poor and disadvantaged from the majority community, seem to have had full access to and support from the state machinery.

These observations matter in the context of electoral politics today, for majoritarianism is being deployed to gain voters at the cost of the weaker sections of society, hurting India’s chances of making progress.

The polarisation during electoral campaigns today was forewarned decades ago by the first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. He wrote presciently on the communal violence outbreak in 1961 in Madhya Pradesh, calling it the result of a “narrow communal outlook whether it is Hindu or Muslim or Sikh or any other”. Nehru found this narrow outlook “more harmful to us than anything else”.

Newspapers Flaming Communal Passion

In a letter to chief ministers on 20 February 1961, Nehru referred to the “deplorable communal incidents occurring in Jabalpur and some other towns of Madhya Pradesh”. He referred to the “widespread attack on Muslims and their houses and shops” as being “pre-planned and organised”. He wrote, “Local newspapers fan the flames [and] communal organisations come to the forefront.”

Nehru’s remarks about local newspapers fanning communal passions is a contemporary reality, in the sense that Hindutva-leaning organisations have been targeting Muslims violently and aggressively appealing for their social and economic boycott, some even calling for genocide.

After the 20 February letter, Nehru wrote more comprehensively about the communal issue to chief ministers on 6 March of the same year. In it, he noted that the upsurge of communal violence in some places in Madhya Pradesh shocked him not merely because of the damage done to life and property but “even more so because it uncovered something that was painful to us”.

What it had uncovered, he said, was how shallow the claims about “nationalism and unity” were. Nehru sadly remarked, “We do not live up to what we say.” He wrote, “Communalism, casteism and regionalism hold us in their grip and often disable us from advancing along the path of our choice”.

Indeed, unlike the present-day leaders of India, Nehru did not shy away from acknowledging his government’s failures. According to him, violence against minorities represented a “failure of our administrative apparatus”. He even accepted that the outlook of many Indians was narrow and, indirectly referring to the cataclysm of Partition, he wrote that “differences” still survive within us.

Courage as Statesman

Nehru was a prime minister and a statesman who could courageously turn the searchlight inwards. He did not hesitate to take responsibility for the pain and suffering of people, regardless of their faith or any other identity. The example he set in the formative stages of our nation is genuinely inspirational.

Can the leaders ruling India, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, take a leaf out of Nehru’s letters to chief ministers and ask themselves if their conduct and actions are in tune with the aspirations and anxieties of the people? In Manipur and other parts of India, sections of our citizenry have lost their lives on being attacked violently because of their faith or beliefs.

Indeed, Nehru did not even hesitate to point the finger at those who belong to the majority community, the Hindus, and hold them to account for their “narrow-mindedness”.

Writing again in the context of the infamous 1961 violence in Madhya Pradesh, he courageously addressed the problem: “…it was the basic communalism and narrow-mindedness of the majority Hindu community that is at fault.” He also wrote, “I would hold to this opinion even if the minority misbehaved to some extent.” In other words, in newly independent India, where the majority community was of the Hindus, they also had to take a significant share of the responsibility for failing to protect the minorities.

Nehru categorically stated, “It is the duty and responsibility of the majority not only to deal with the minorities fairly but to win them over, to make them feel that they belong to the nation and not merely to a smaller group in it, to have a sense of solidarity with others.” Sadly, he had to acknowledge that India was “far from having reached this goal”.

But Nehru was not only apportioning blame. He looked to the future with hope, for he said there was no question of surrendering to divisive forces representing a narrow communal outlook. He harboured no illusions about how communitarian beliefs were not ingrained in India’s long history or the lived experiences of its people for millennia. Indeed, he presciently wrote that it is “under cover of communalism that reactionaries function”. Put another way, conflicts between communities are neither tradition nor religiously sanctioned in India, but a cynical political gambit that has started to “flaunt itself even in public and is challenging our basic policies”.

Nehru’s Questions

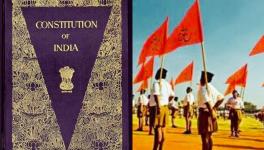

Nehru was candid enough to admit that despite our Constitution and brave talk, “we often function in narrow spheres, communal, caste, region and language”. He urged people to search their hearts and discover the causes of such failures. According to him, the test of our success would not be our bald assertions that everything was well but whether the minority in India feels it is getting its due in India’s public life, including its economic development and other vital spheres of our society.

Nehru’s words in 1961 resonate in India in 2023, specifically against the backdrop of majoritarianism and polarisation.

His letters are worth recalling especially since they highlight the public postures and statements that the reactionary forces are taking today. Then, as now, the aim is to divide people so that the public policies shaped for the betterment of the nation can be challenged.

The forces that control the state apparatus today are challenging India’s basic policies, and the very idea of India is under threat. That is why Nehru’s words are immensely significant. Defending the Constitution and the republic against backsliding further is crucial. And, arduous as the task may sound, defeating such forces is electorally simple and feasible—the alternative, if it comes to fruition, may prolong India’s existential crisis.

The author served as an Officer on Special Duty to President of India K R Narayanan. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.