“You Have to Love a Text to Want to Translate it”

Bengal in the 1940s. Having overcome the famine and the revolt of the sharecroppers, Bengal’s peasants are uniting. Work is scarce and wages are low. There is barely any food to be had. The proposal for the formation of Pakistan, the elections of 1946, and communal riots are rewriting the contours of history furiously. Amidst all this, in an unnamed village, a familiar corporeal spirit plunges into knee-deep mud. This is Tamiz’s father, the man in possession of Khwabnama.

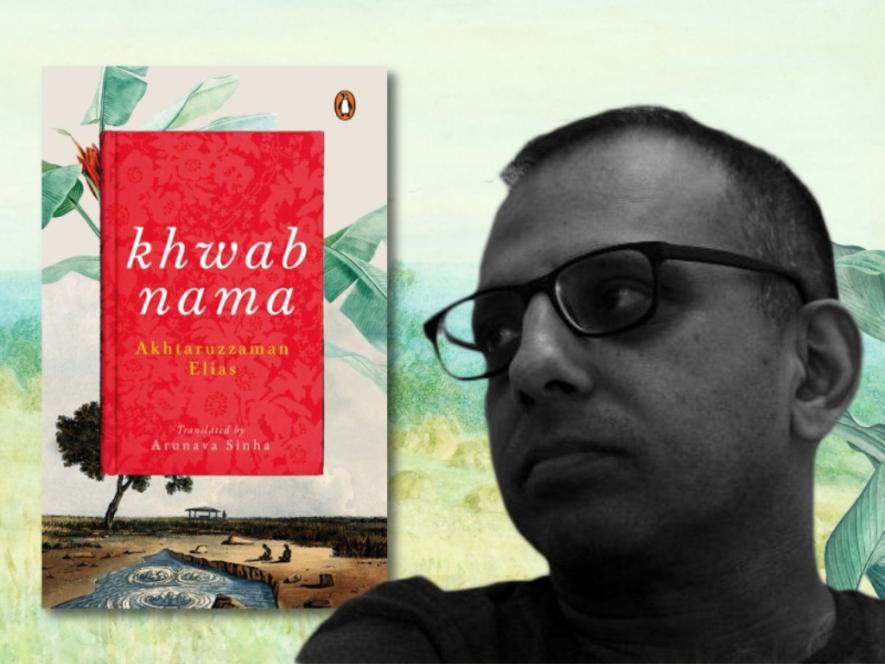

Written by Akhtaruzzaman Elias and translated into English by Arunava Sinha, Khwabnama documents the Tebhaga movement wherein peasants demanded two-thirds of the harvest they produced on the land owned by zamindars.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Arunava Sinha talks about translating Khwabnama and more.

On Khwabnama:

Githa Hariharan (GH): This is, in all ways, a large book. How did you, as translator, keep steady on your path — through the maze of myth, dream, poetry, song, and multiple voices?

Arunava Sinha (AS): At about 190,000 words, it’s the longest novel I’ve translated so far. Fortunately, the hard work was already done by the author. I only had to follow his text closely, without worrying about how all the elements in the story would come together. So there was no big-picture problem. And when you live in a book long enough, as you must with any book you translate, but most definitely with Khwabnama, you start hearing and seeing everything in it. So you work with the text very closely, solving problems at the level of words and phrases and sentences and sounds, and then you step back and see that it has miraculously come together with all those elements you mentioned.

GH: Again, this tapestry of the collective voice has as its pegs major events — upheavals — from famine which remains a fresh memory, to peasant struggle, to partition and its terrible costs. The author must have seen powerful connections between past and present as he wrote the novel. Did you, as reader and translator, find yourself connecting past and present as well, though perhaps in a different way?

AS: Yes, I trace my own history to the history and geography and politics of this novel, not a lived history but, much like that of the characters, an inherited and an absorbed history. So many of the things in this novel resounded beyond the text, not the least of them being the fact that the founder of the Communist Party in the erstwhile East Pakistan after the Partition was an ancestor of mine. But none of this played a role in the translation, where in fact, everything but the immediacy of the text recedes into the background.

GH: The style, I can see, is challenging. How did you manage to evoke so many registers — from the almost incantatory language of mythmaking, to the local flavour of the songs, to the earthy colloquial of the everyday lives of fisherfolk and farmers?

AS: Thank you for suggesting the multiple registers have come through. Here it works at two levels. Let’s call them content and form, for the sake of simplicity. Since each character was anyway saying something unique to them, including, of course, the invisible narrator—and that’s obviously the author’s skill—as was the inserted sections such as the songs, maintaining fidelity to this content in each case automatically separated each of the voices. The rest was worked on through a combination of choice of words, length of sentences, and so on. I didn’t try to reproduce the dialect in English dialect, as that would have created a false specificity of location. But translation is so much a matter of hearing the text that most often you’re working on taking what you’re hearing, rather than what you’re seeing in the form of words, into a new language.

On translation:

GH: You have translated such a range of work — in terms of genre, author, time period — that I want to get a sense of your journey. What did you begin with? And how did you move, say, from fiction to poetry? Or from the contemporary to the classical? And finally: is your translation necessarily a one-way journey, with Bangla as the source and English as destination?

AS: I began with Sankar’s Chowringhee, which very effectively straddles the literary and the popular in terms of form and content, depth and width. And then, because all the Bangla books I’d loved reading came rushing back to me with the potential for being translated, I pretty much went forward and backward, up and down, picking books rather than periods or genres. Over a period of time, I started experimenting with poetry in private, after vowing never to. It was more like riyaz—which is something I strongly believe in—while also being an effort at pushing the envelope. So I began to seek out ‘difficult’ texts, which in turn led me to Khwabnama. And also to translating into Bangla, which I have done three of so far. One has been published, and two more are due this year.

GH: At the heart of translation is, obviously, its relationship with the original text. This requirement — of staying true — is often debated. I like the Borgesian view that the original is unfaithful to the translation. How do you respond to the frequent (and occasionally churlish) complaint that English simply does not have true counterparts for words in Bangla or Marathi or Tamil?

AS: You do have to stay true, but not in a narrow sense. A text is not just a collection of words. It’s music, silences, mysteries, allusions, directness, obliqueness, and so much more. So of course you need fidelity towards all of those, and, most of all, to the affect—the overall impact it has on you as a reader. Quibbling over the precise equivalent of words is a pointless and pedantic (as you say, churlish) exercise. And somehow, it’s aimed at delegitimising translation, by those who wish literatures to be imprisoned in their respective original languages.

I interpret Borges’s classic Borgesian quip to mean that the original tends to be reduced to a so-called essence, which denies the translation all the richness it can achieve.

GH: Multilingualism is only one aspect of our many diversities, and translation — between and among languages and ways of life — seems a critical exercise for survival, if not good health. I have always felt translation should be part of our education system. I see you teach translation. What are the ways in which we can scale this up into our education system at all levels? A detail: how do you teach translation when you do not know the source or target language?

AS: Indians are naturally multilingual, it’s a lived experience in this country, where we’re translating in our heads all the time. We have to work on converting this into multiliteracy. I strongly believe school and college students should be reading simultaneously in at least two languages. The medium of instruction can be anything, English or otherwise, but students can and should be reading literary works, newspapers and magazines, and so on, in their mother tongues alongside. I feel this will change, if not transform, the way we perceive ourselves, others, the country, the world, everything. And this can be achieved easily through the curriculum, for every language has wonderful texts to be read.

As for teaching translation, what I really teach is first, to love translation, and second, the choices, parameters and strategies for translating. Accuracy is not difficult to achieve, anyone can do that with a command over the languages and a couple of good dictionaries. So it isn’t about how to translate a particular word, phrase or sentence, but about what questions to ask oneself when translating.

GH: Finally, the relationship between the translator and the text to be translated: my friend and mentor in publishing, Sujit Mukherjee, used to say that when you choose a text to translate, it is actually a compliment. You love the text so much that you want to share it with others. Your view?

AS: You have to love a text to want to translate it. It’s very similar to liking a song so much that you start singing it for yourself. I’m not sure about translating so others can read it, that’s there at the back of your mind of course, but if I’m being honest for me the real pleasure comes from the act of translation, from being able to write a book I love, only in another language. And if you don’t love a book, the translation won’t work, it can be coldly competent, but it will not have the life of the original work.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.